Five Requirements Prioritization Methods

When customer expectations are high and timelines are short you need to make sure your project team delivers the most valuable functionality as early as possible.

Prioritization is the only way to deal with competing demands for limited resources.

Stakeholders on a small project often can agree on requirement priorities informally. Large or contentious projects with many stakeholders demand a more structured approach. You need to removes some of the emotion, politics, and guesswork from the process. This article discusses several techniques teams can use for prioritizing requirements and some traps to watch out for.

Two Big Traps

Be sure to watch out for “decibel prioritization,” in which the loudest voice heard gets top priority, and “threat prioritization,” in which stakeholders holding the most political power always get what they demand. These traps can skew the process away from addressing your true business objectives.

In or Out

The simplest method is for a group of stakeholders to work down a list of requirements and decide for each if it’s in or it’s out. Refer to the project’s business objectives to make this judgment, paring the list down to the bare minimum needed for the first iteration or release. When that iteration is underway, you can go back to the previously “out” requirements and repeat the process for the next cycle. This is a simple approach to managing an agile backlog of user stories, provided the list of pending requirements isn’t too enormous.

Pairwise Comparison and Rank Ordering

People sometimes try to assign a unique priority sequence number to each requirement. Rank ordering a list of requirements involves making pairwise comparisons among all of them so you can judge which member of each pair has higher priority. This becomes unwieldy for more than a few dozen requirements. It could work at the granularity level of features, but not for all the functional requirements for a good-sized system as a whole.

Rank ordering all requirements by priority is overkill, as you won’t be releasing them all individually. You’ll group them together by release or development iteration. Grouping requirements into features, or into small sets of requirements with similar priority or that otherwise must be implemented together, is sufficient.

Three-Level Scale

A common approach groups requirements into three priority categories. No matter how you label them, if you’re using three categories they boil down to high, medium, and low priority. Such prioritization scales usually are subjective and imprecise. To make the scale useful, the stakeholders must agree on what each level in their scale means.

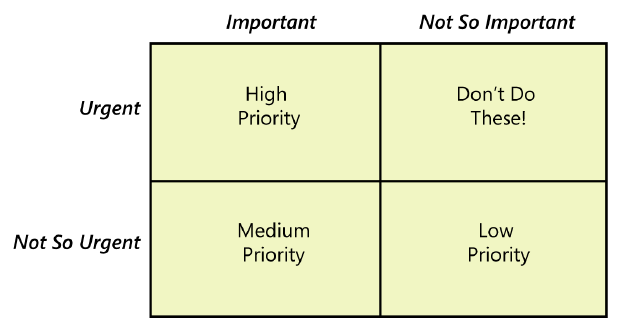

I like to consider the two dimensions of importance and urgency. Every requirement can be considered as being either important to achieving business objectives or not so important, and as being either urgent or not so urgent. This is a relative assessment among a set of requirements, not an absolute binary distinction. These alternatives yield four possible combinations (Figure 1), which you can use to define a priority scale:

* High priority requirements are important because customers need the capability and urgent because they need it in the next release. Alternatively, there might be compelling business reasons to implement a requirement promptly, or contractual or compliance obligations might dictate early release. If a release is shippable without a particular requirement, then it is not high priority per this definition. That’s a hard-and-fast rule.

* Medium priority requirements are important (customers need the capability) but not urgent (they can wait for a later release).

* Low priority requirements are neither important (customers can live without the capability if necessary) nor urgent (customers can wait, perhaps forever).

Watch out for requirements in the fourth quadrant. They appear to be urgent to some stakeholder, perhaps for political reasons, but they really aren’t important to achieving your business objectives. Don’t waste your time implementing these—they don’t add sufficient value to the product. If they aren’t important, either set them to low priority or scrub them entirely.

Figure 1. Requirements prioritization based on importance and urgency.

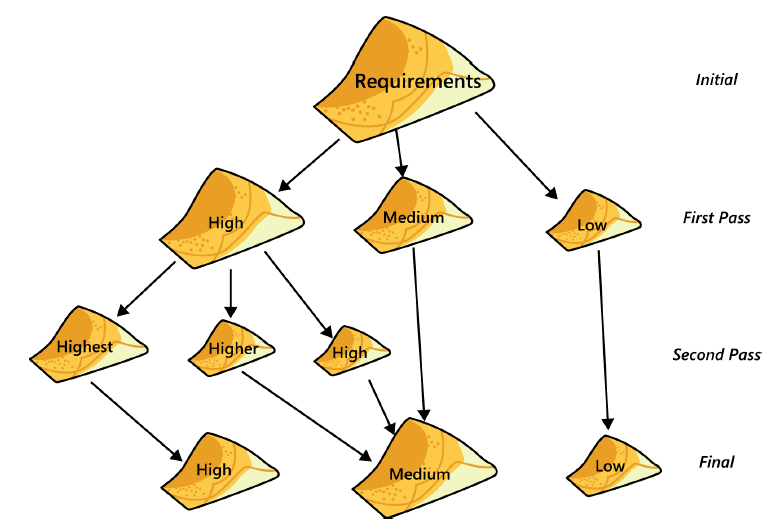

On a large project you might want to perform prioritization iteratively. Have the team rate requirements as high, medium, or low priority. If the number of high-priority requirements is excessive and you can’t fit them all into the next release, perform a second-level partitioning of the high-priority ones into three groups. You could call them high, higher, and highest if you like, so people don’t lose sight of the fact that they were originally designated as high.

Those requirements rated “highest” become your new group of top-priority requirements. Then, group the “high” and “higher” requirements in with your original medium-priority group (Figure 2). Taking a hard line on the criterion of “must be in the next release or that release is not shippable” helps keep the team focused on the truly high-priority capabilities.

Figure 2. Multipass prioritization keeps the focus on a manageable set of top-priority requirements.

Watch for requirement dependencies when prioritizing with the three-level scale. You’ll run into problems if a high-priority requirement depends on another that’s planned for later implementation.

MoSCoW

The four capitalized letters in the MoSCoW prioritization scheme stand for four possible priority classifications:

Must: The requirement must be satisfied for the solution to be considered a success.

Should: The requirement is important and should be included in the solution if possible, but it’s not mandatory to success.

Could: It’s a desirable capability, but one that could be deferred or eliminated. Implement it only if time and resources permit.

Won’t: This indicates a requirement that will not be implemented at this time but could be included in a future release.

The MoSCoW scheme changes the three-level scale of high, medium, and low into a four-level scale. It doesn’t offer any rationale for making the decision about how to rate the priority of a given requirement compared to others. MoSCoW is ambiguous as to timing, particularly when it comes to the “Won’t” rating: does it mean “not in the next release” or “not ever?” The three-level scale that considers importance and urgency and focuses specifically on the forthcoming release or iteration.

Agile projects often use the MoSCoW method, but I’m not a big fan of it. Here’s how one consultant described how a client company actually practiced the MoSCoW methods:

All the action centers around getting an “M” for almost every feature or requirement that is captured. If something is not an “M” it will almost certainly not get built. Although the original intent may have been to prioritize, users have long since figured out to never submit something that does not have an “M” associated with it.

Do they understand the nuanced differences between S, C, and W? I have no idea. But they have figured out the implications of these rankings. They treat them all the same and understand their meaning to be “not happening any time soon.”

$100

One way to make prioritization more tangible is to cast it in terms of an actual resource: money. In this case, it’s just play money, but it’s money nonetheless.

Give the prioritization team 100 imaginary dollars to work with. Team members allocate these dollars to “buy” items they’d like to have implemented from the set of candidate requirements. Allocating more dollars weights the higher-priority requirements more heavily. If one requirement is three times as important to a stakeholder as another, she might assign nine dollars to the first requirement and three dollars to the second.

But 100 dollars is all the prioritizers get—when they’re out of money, nothing else can be implemented, at least not in the release they’re currently focusing on. You could have different participants in the prioritization process perform their own dollar allocations, and then add up the total number of dollars assigned to each requirement. That will show which ones collectively come out as having the highest priority.

Watch out for participants who game the process to skew the results. If you really, REALLY want a particular requirement, you might give it all 100 of your dollars to try to float it to the top of the list. In reality, you’d never accept a system that possessed just that single requirement.

Nor does this scheme take into account any concern about the relative amount of effort needed to implement each of those requirements. If you could get three requirements each valued at $10 for the same effort as one valued at $15, you’re likely better off with the three. The scheme is based solely on the perceived value of certain requirements to a particular set of stakeholders, which is a limitation of many prioritization techniques.

It’s Not All Going to Fit

Sometimes customers don’t like to prioritize requirements. They’re afraid they won’t ever get the ones that are low priority. Maybe they won’t. But if you can’t deliver everything, make sure you do deliver those capabilities that are most important to achieving your business objectives. Prioritize to focus the team on delivering maximum value as quickly as possible.

top online casino real money

sugarhouse casino online sportsbook https://download-casino-slots.com/

us online casino

real vegas online casino https://firstonlinecasino.org/

$10 deposit online casino

unibet online casino https://onlinecasinofortunes.com/

what is the best online casino for real money

casino gambling online https://newlasvegascasinos.com/

mobile casino online

new online casino with free signup bonus real money usa https://trust-online-casino.com/

online casino hosting sanjeev beemidi

aladdin casino online https://onlinecasinosdirectory.org/

ceasars casino online

casino online gambling https://9lineslotscasino.com/

golden nugget online casino michigan

online casino nevada https://free-online-casinos.net/

liberty online casino

nj online casino free money https://internet-casinos-online.net/

mgm online casino

soaring eagle online casino https://cybertimeonlinecasino.com/

borgata pa online casino

vegas 777 online casino https://1freeslotscasino.com/

new vegas online casino

free casino games online https://vrgamescasino.com/

real money online casino

borgota casino online https://casino-online-roulette.com/

online casino live roulette

casino online slots https://casino-online-jackpot.com/

online casino live roulette

bet online casino no deposit bonus codes https://onlineplayerscasino.com/

legit online casino

online casino big winners https://ownonlinecasino.com/

snoqualmie casino online

online casino with $5 minimum deposit https://all-online-casino-games.com/

casino games online real money

choctaw casino online https://casino8online.com/

best vpn for firestick 2022

best vpn for streaming https://freevpnconnection.com/

best vpn for windows free

free vpn? https://shiva-vpn.com/

free vpn apps

kroger vpn https://freehostingvpn.com/

buy vpn for windows

free vpn service https://ippowervpn.net/

what is vpn service

buy a vpn server https://imfreevpn.net/

avast secure line vpn

buy vpn online https://superfreevpn.net/

best anonymous vpn

cyberghost vpn free trial https://free-vpn-proxy.com/

best vpn for ios

free vpn into china https://rsvpnorthvalley.com/

hispanic gay dating sites

gay trucker dating https://gay-singles-dating.com/

dating guys when 18 gay

gay dating madison wi https://gayedating.com/

white gay liberal dating interracial to avoid seen as racist

is it smart for gay teens to use dating apps https://datinggayservices.com/

single web site

free single dating service https://freephotodating.com/

internet dating

interracial dating site https://onlinedatingbabes.com/

asian online dating

fuck2date69 https://adult-singles-online-dating.com/

shemale dating

adult dating married https://adult-classifieds-online-dating.com/

dating awareness women's network

best internet dating websites https://online-internet-dating.net/

meet single women online

dating services https://speedatingwebsites.com/

meet single women online

japanese dating https://datingpersonalsonline.com/

free web date site

dating online best websites https://wowdatingsites.com/

free f

dating free online sites https://lavaonlinedating.com/

japanese singles dating sites

dating websites https://freeadultdatingpasses.com/

dating sites online

online dating sites for free 100% https://virtual-online-dating-service.com/

dating website no credit card

meet women locally https://zonlinedating.com/

dating naked

best single sites https://onlinedatingservicesecrets.com/

online casino sverige

nj online casino promo code https://onlinecasinos4me.com/

virginia online casino

sugarhouse online casino pa https://online2casino.com/

wild casino online

pa online casino real money no deposit https://casinosonlinex.com/

gay webcam and chat

gay chat cams https://newgaychat.com/

free gay webcam chat rooms

profile tube boys user gay chat boi https://gaychatcams.net/

free gay bays chat

chat gay chat https://gaychatspots.com/

westchester gay chat rooms

gay dot com chat room https://gay-live-chat.net/

gay chat pittsburgh

gay chat rooms ring central https://gayphillychat.com/

gay phone chat manhole

teen chat rooms 13-16 gay https://gaychatnorules.com/

free gay bi chat lines in seattle wa

free gay chat roulette https://gaymusclechatrooms.com/

gay cam chat

gay massachusetts chat no sign up https://free-gay-sex-chat.com/

gay massachusetts chat

gay chat room https://gayinteracialchat.com/

ghost writer college papers

write my paper online https://term-paper-help.org/

custom papers writing

do my college paper https://sociologypapershelp.com/

write my custom paper

paper writing help https://uktermpaperwriters.com/

pay for a paper

finished custom writing paper https://paperwritinghq.com/

best online paper writing service

who can write my paper https://writepapersformoney.com/

scientific paper writing services

buy papers online https://doyourpapersonline.com/

best paper writing service reviews

what should i write my paper on https://top100custompapernapkins.com/

pay to do my paper

write my paper college https://researchpaperswriting.org/

buying college papers online

buy cheap paper https://cheapcustompaper.org/

online paper writing service

help write my paper https://writingpaperservice.net/

write my paper for me cheap

write my paper co https://buyessaypaperz.com/

Anonymous

paper helper https://mypaperwritinghelp.com/

pay someone to write my paper

college paper writers https://writemypaperquick.com/

write my english paper

pay to write paper https://essaybuypaper.com/

help writing papers for college

write my paper for me https://papercranewritingservices.com/

need help writing a paper

write my paper for cheap https://premiumpapershelp.com/

scientific paper writing services

paper helper https://ypaywallpapers.com/

buy academic papers

pay someone to write paper https://studentpaperhelp.com/

2reservation

1thereabouts