It’s Time to Put Value in the Driver’s Seat

Deliver value. It is the mantra of every agile or lean team and a big part of the conversation among traditional or waterfall teams as well. You would expect, then, for all teams to define a product’s value explicitly and transparently—to make it the basis for every decision, the determining factor behind every potential product feature. Yet, too often this is not the case.

Let’s explore how successful teams define value, use it to drive decisions, and consider and reconsider value throughout a product’s lifecycle.

Let Value Be Your Guide

According the Value Standard and Body of Knowledge value is “a fair return or equivalent in goods, services, or money for something exchanged.” In other words, value is what you get for what you give up.

What one company considers valuable, at a certain time, might be completely different than what matters to another company, or to the same organization at another point in time. For example, one team we recently worked with selected a minimum set of product features, or slice of functionality, that could be delivered to their primary end users within two months, so as to stay within the bounds of a highly profitable purchase agreement. Another organization identified the set of features that simultaneously reduced operating costs and flagged conditions in the field that could risk life and limb.

So how did these teams decide on what to deliver? What enabled them to quickly, transparently, and collaboratively select the highest value features? They relied on value to steer their product in the right direction.

Choose Your Destination

Defining a product’s desired result, before building it, is fundamental to that product’s success. As the old saying goes, if you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there. Successful agile teams start by determining where they want to finish.

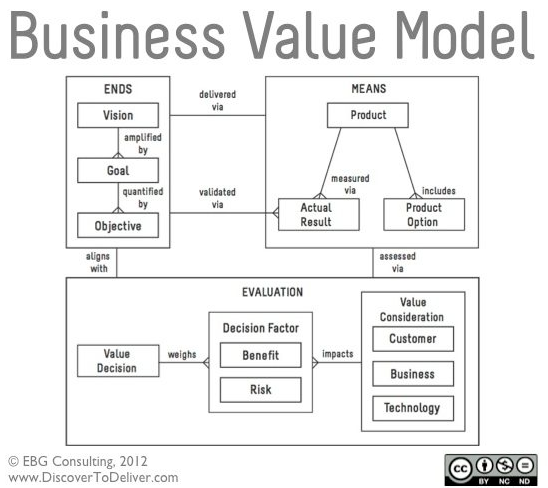

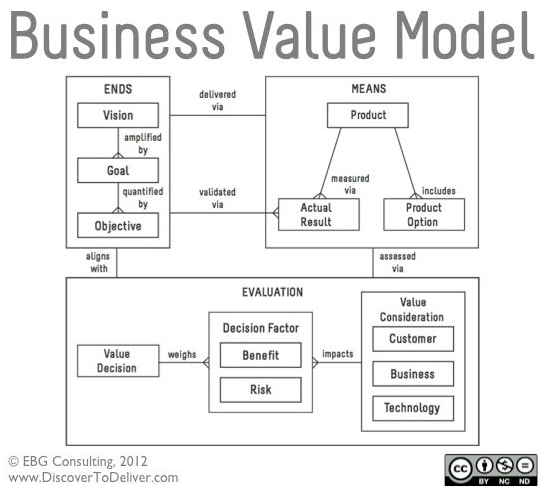

In our first article in this series, we described how product stakeholders from the customer, business, and technology realms become collaborating partners. These product partners envision the product, define goals, and specify measurable objectives, creating a high-level view of the desired product outcomes. These key markers describe and quantify the product’s anticipated value, ensuring that the team is always moving in the correct direction.

One aspect to consider is the tangible, financial qualities, including measures such as IRR (internal rate of return), ROI (return on investment), TCO (total cost of ownership), and EVA (economic value added). Value, though, is about more than money; it is also about intangible aspects, such as user experience, joy, belonging, convenience, sense of well being, trust, alignment to strategy, upsell potential, or brand projection. These intangibles can often be as or more important than tangible value qualities, such as cost or profit margins. Though these intangible considerations are more elusive to measure, they can be quantified by accounting for uncertainty and risk. (For more on this, we recommend Hubbard’s How to Measure Anything).

One of the ways to uncover both tangible and intangible value is to have the product partners explore and share their own value considerations. A value consideration is some variable that is used when assessing the value of your product options. For example, the customer partners might include safety or a convenient-to-use product among their value considerations. Business partners (the people sponsoring the product’s development) might be most concerned about market positioning or protecting the company’s reputation. The technology partners (those who build the product) might be more interested in feasibility and compatibility with existing and future architecture. Making all of these varied (and often competing) value considerations transparent is crucial for making good decisions.

Identify Potential Hazards

Another aspect to consider when making value decisions is risk. Like value, risks change with time and can impede, mitigate, or even obviate delivered value. These risks include rework (if the wrong thing is delivered or technical debt is incurred), noncompliance, opportunity cost, and more. We recommend you consider risks along the same categories as we consider product partners: customer, business and technology.

Dependencies—product and project, internal and external—also constrain product decisions. For example, the partners need to understand the consequences of deviating from an optimal sequence, in both time and cost.

Plot the Preliminary Route

With the guideposts of vision, goals, and objectives in sight, and a clear view of all the tangible and intangible value considerations, the product partners can select the best set of high-value product features (options) for the next planning horizon. (In our second article in this series we define options and describe how teams discover them for all 7 Product Dimensions.) To do this, they consider the costs, benefits, risks, dependencies, and value considerations of each option. They then adjust each option’s value up or down accordingly, always ensuring the option is aligned with the product’s vision, goals and objectives.

Together, the desired outcomes, value considerations, benefits, and risks make up the business value model for a product. The product partners use the value model during discovery and delivery to guide their decisions. In the next article in this series we’ll describe how the partners plan collaboratively, choosing decision-making rules and the timing of the decisions, favoring the last responsible moment.

Adjust Course As Needed

Discovering value isn’t a one-and-done activity. The product partners repeat the process at every planning horizon: the long-term (Big-View), the interim-term (Pre-View), and the short-term (Now-View). Throughout the product’s lifecycle, the partners stay alert to changes in market conditions, availability of resources, costs of delay, etc., and their potential impact on the product, modifying the business value model as needed.

After each delivery cycle, the partners determine if what was delivered actually realizes the anticipated value. This comparison may uncover gaps to be addressed in future releases. Though the Lean Startup movement has made this seem like a new concept, we’ve long had a name for it in requirements engineering: validation. In Discover to Deliver, we call it “confirm to learn.”

Ensure Optimal Visibility

Before value can drive decisions, it must be defined, visible, and well understood by all concerned. Teams need to understand what value means through the eyes of the stakeholders—the product partners from business, customer, and technology. They can then view potential product options (requirements) in the context of these values to choose the most valuable set of features for each release.

When was the last time you collaboratively discussed and purposefully validated your value assumptions? Take some time in your next planning session to honestly and transparently define your product’s value, so that value truly becomes the driving force behind your product decisions.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

References:

Gottesdiener, Ellen and Mary Gorman. Discover to Deliver: Agile Product Planning and Analysis. EBG Consulting, 2012.

Hubbard, Douglas. How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in Business. 3rd edition, Wiley, 2014.

SAVE International. Value Standard and Body of Knowledge. June 2007. Available online here.