Requirements vs. Design – Does it Really Matter?

Much has been written recently about design in the business analysis field. Some writers have even suggested that since most or all of what we do is about design, then requirements don’t matter anymore. It is popular – even exciting perhaps – for BAs to think of ourselves as designers, since much of the work we do results in solutions. We don’t disagree with the trend and the main concern prompting us to write this article is to point out the importance of including the “as is” state as part of any requirements – or should we say design – effort.

In thinking about the topic it is our opinion that a) perhaps people lack some perspective on where and how business analysis has evolved and b) the debate about requirements vs. design may be mostly one of semantics. Over the years, Elizabeth and I along with many others, have worked hard to help the BA profession carve out its place in the business world.This effort has involved moving from the extremes of having either a technical, systems analyst role or an administrative business “super user” role do the business analysis work.

Part of the impetus for the new design focus has been a strong aversion by some in the Agile community to business analysts or business analysis. Those who feel strongly tend to concentrate on the design aspects of a new product and don’t see the need for much if any actual analysis of the business or business need. (See Tony Heap’s blog its-all-design.com for an example. ) If business analysts are now just designers and we need little analysis, we are moving back to the earlier systems analyst role. Although that might be a satisfying career move for some, it does not usually serve the organization well. To say that we don’t need to worry about requirements is missing the essence of what a business analyst can and should be.

Early in Rich’s career he worked as a programmer-analyst doing COBOOL programming with a variety of databases. That was a euphemism for a role that was 90% design/programming and 10% analysis as we know it today. In thinking back, our jobs then were to implement decisions made at higher levels in the organization, both from the CIO and business management levels. Although we met occasionally with business stakeholders, we generally worked to adapt the business to available technology. While today’s “design” does not imply that we have to ignore business needs, it does suggest that we will focus on solutions without truly understanding the needs.

Haven’t we moved beyond that approach over the last few decades?

Let’s walk through some reasons why the emphasis on design over analysis is an issue. Being only or mostly interested in “design” implies that we don’t care about the “as is” state anymore, as is suggested in recent articles, blogs, and discussion groups. (See David Morris’ article, We Are All Designers Now. ) Without understanding the current situation, we cannot hope to understand:

- How end users’ jobs will change with the implementation of the new product or product increment. If we do not know the extent of the change we cannot help workers adapt to the change, which increases the risk of lack of buy-in, unhappiness, and even possible sabotage.

- Which of the issues with the “as-is” need to be addressed. If we implement new processes and systems without curing existing ills, we will lose credibility.

- No new product or solution is devoid of the current state. Even when we create a brand new product or service, it must fit into the current environment and infrastructure. That means we will have requirements that must be met – not designs – to ensure the new solution contains existing functionality that works and without which the new product cannot perform adequately.

- In addition, most of us work on projects that are not entirely new products, but replacements and enhancements of existing systems or processes. These efforts need plenty of analysis of the “as is” state and its corresponding requirements to make sure the changes we bring will fit into the rest of the business operation.

- Even for brand new products, there are many business rules and decisions that apply across projects and should be taken into account for the project at hand. For example, the new Training Management System we built for our web site was contracted to a development company. The “specification” the development company used represented our decisions (i.e., business requirements) about what was to be built. The specification was clearly not a design – that was done by the developers – but represented our needs and requirements for the new system.

- The BABOK® Guide version 3 talks about requirements being the representation of a need and design as a representation of a solution. That is a workable distinction, although it is a bit awkward to talk about “designs” at the same level as requirements. To understand the distinction better, it helps to substitute the words for the process instead of the outputs:

- Analysis is understanding the needs and requirements and communicating them to the builders of a solution.

- Design is how new features and functions will be incorporated into a solution, plus maintaining existing requirements that should be kept in the new solution.

The last point is perhaps our biggest concern with the new thinking. The business analysis community has fought for years to keep analysis distinct from technical design. In the end, we don’t care that fashioning a solution is called design. After all, what is now being called design is nothing different from calling the output of the process “To-be” requirements.

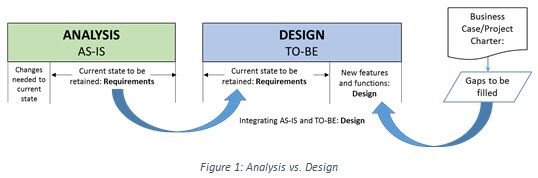

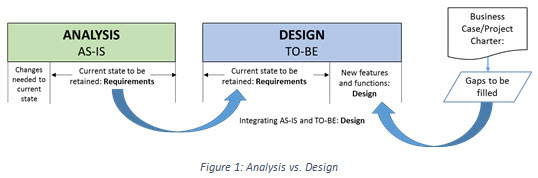

To illustrate our point, consider Figure 1. The example might be a typical enhancement to an existing system or process. In the traditional business analysis approach, the “as-Is” state is analyzed as a starting point to capture processes, data, and interactions that must be kept for any new solution. Those are “as-is” requirements.

The “current state to be retained” in the “Design” box below are also requirements. They could be processes, data, or user and system interfaces. The design process comes into play when determining how to integrate them with the new features being added. Those new features could equally be called “To Be” requirements as well as design. This is not technical or physical design, but the “logical” design mentioned earlier.

Examples of “To Be” requirements (or design if you prefer) include many traditional BA outputs including:

- Process models showing an “As Is” as well as a new business process.

- Data models showing “To Be” data requirements and business rules relating to the relationships between entities.

- Use Case models with interaction requirements and corresponding business rules.

- Prototypes and mock-ups indicating interface requirements. These models tend to cause the most “overlap angst” with other staff such as UX experts. Data models come in a close second in the “don’t step on my turf” confrontations.

- Interfaces with other systems.

SUMMARY

In the end as long as we are talking about “logical” design and not technical or physical design, the authors agree with the current trend calling BAs designers. In actuality, BAs have always been designers because we help people conceptualize and visualize solutions that will help businesses meet goals and objectives through solutions. As long as we don’t forget the importance of “As Is” and “To Be” requirements and the part they both play in any solution, then emphasizing design over requirements becomes to us an academic argument.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

The Best Reason to call BAs Designers?Perhaps the biggest reason to call our work design has nothing to do with the BABOK or Agile. It is financial. Yes, the accountants are reluctant to capitalize analysis work, but they do allow capitalizing design work. This makes a huge difference for funding of projects since capitalized costs can be spread out over the useful life of the product being built. Elizabeth and I have a friend who runs a consulting firm in Minneapolis. He tells us his clients won’t typically pay for “analysis” or “requirements” work. But, he also understands the value of business analysis for the success of his company’s projects. So if he couches the same work as “design,” the clients are more willing to pay for it. |

About the Authors

Elizabeth Larson, PMP, CBAP, CSM, PMI-PBA is Co-Principal and CEO of Watermark Learning and has over 30 years of experience in project management and business analysis. Elizabeth’s speaking history includes repeat presentations for national and international conferences on five continents.

Elizabeth has co-authored five books on business analysis and certification preparation. She has also co-authored chapters published in four separate books. Elizabeth was a lead author on several standards including the PMBOK® Guide, BABOK® Guide, and PMI’s Business Analysis for Practitioners – A Practice Guide.

Richard Larson, PMP, CBAP, PMI-PBA, President and Founder of Watermark Learning, is a successful entrepreneur with over 30 years of experience in business analysis, project management, training, and consulting. He has presented workshops and seminars on business analysis and project management topics to over 10,000 participants on five different continents.

Rich loves to combine industry best practices with a practical approach and has contributed to those practices through numerous speaking sessions around the world. He has also worked on the BA Body of Knowledge versions 1.6-3.0, the PMI BA Practice Guide, and the PM Body of Knowledge, 4th edition. He and his wife Elizabeth Larson have co-authored five books on business analysis and certification preparation.