The Bad Ass BA Observes the “Hunt for the Right BA”, Part 2

In the January article, I talked about the job seeker’s difficulty sorting through job descriptions for business analysts. In Part 2, I want to turn it around and look at the “specialist” vs. “generalist” question that we face as we create our resumes – how do we position ourselves as we respond to job postings?

In the Feb 2011 IIBA Newsletter, Laura Brandenburg, IIBA Career Center Product Manager, said, in her article, “5 Steps to Becoming a Business Analyst”

Although IIBA® holds us business analysts together under a unified understanding of business analysis, the real world of business analyst job roles is often messy and difficult. BA roles, as we learn in the competency model, fall into three main buckets:

- Generalists, who perform a wide variety of business analysis activities

- Specialists, who use a limited set of techniques or a single methodology

- Hybrids, who do business analysis within another job role

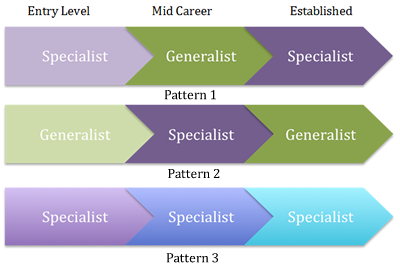

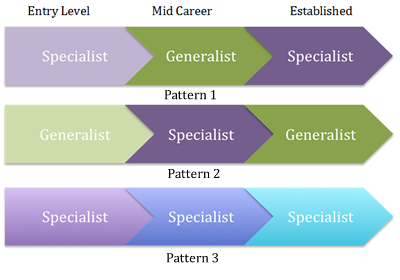

I think there’s a little more to consider. We have to put the generalist vs. specialist discussion in the context of the course of our careers, entry-level, mid-career, experienced-and-having-too-much-fun-to-retire. Here are three typical patterns:

In Pattern 1 you began your career doing software testing in under watchful supervision. Your manager was pleased with your instinctive planning and thoroughness and arranged for formal training in quality assurance. Along the way you discovered use cases and the iterative development. You became a QA generalist for software products, often requested by product managers for “dot oh” releases. Over time, your role evolved into a business analyst role with a specialization in testing activities.

In Pattern 2, you were hired as a business analyst because that’s the title all straight-out-of-college entry-level technical people were given until the manager figured out what you were good at. You had no clue what the BA role was or how to do it. You were given all kinds of work to do, and by asking questions you just figured it out. Because you were able to establish a good working relationship with Group X, you became the go-to person for their application, helping them map their business processes, determining their requirements, designing the user acceptance tests, often coding the changes and jacking the new code into the release environment. A larger company that has better software deployment practices bought out your company; you are no longer allowed to hot swap modules into the production environment. Instead, thanks to your new ITIL Foundations certificate, you became the BA manager for the new group that absorbed Group X.

In Pattern 3, the specialist pattern, you came out of school with a strong database background. You hired into a company that was transitioning from an in-house built HR system to PeopleSoft and became a data migration SME in no time flat. Because you showed that unusual combination of communication and analysis skills, your role shifted from database developer to functional requirements specialist to HRIS business analyst. Over the years your knowledge of PeopleSoft has become greater, both in depth (the integration of PeopleSoft to the company’s ERP system) and breadth (all the different business teams that use PeopleSoft and their wide variety of needs). You started speaking at conferences and writing articles for trade journals. Eventually, you started your own consulting company and now you are traveling the world, helping other companies with their PeopleSoft projects.

There are risks and benefits to both being a generalist and a specialist by the time you are at mid-career. In a nutshell, the risk to being a specialist is that you may become so narrowly focused as to limit your career growth options. The risk of being a generalist is that you may be lacking in-depth knowledge that would make you instantly useful to a hiring manager. The benefit of being a specialist is that if you have the high-demand skills, the likelihood of spending much time on unemployment goes down. The benefit of being a generalist is that you see the patterns across organizations and industries – your big picture view can make you extremely valuable to the right employer. Moreover, an employer who is looking for a generalist is likely to have an expectation of teaming you with subject matter experts.

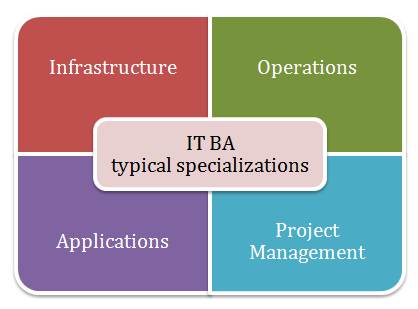

How can an IT BA become a generalist? In the world of IT, Business Analysts tend to cluster in one of four areas, infrastructure, applications, operations and project management.

Project Management. Glenn Brulé coined the term “PooMBA”, a person who is paid one salary to do two jobs. In some back water IT environments, BAs are still “junior PMs”. There are also BAs who are acquiring and refining their project management skills by voluntarily taking on these types of responsibilities.

Infrastructure. The business analyst who has a lot of infrastructure experience may have a specialist title, e.g., network specialist or security specialist. While their job description lists all the technical expertise they are expected to have, the description may gloss over the crucial role they play in communicating with other technical teams. Middleware specialists e.g., TIBCO developers often have an Applications Developer title. While their focus may be on the low level functional requirements, the knowledge and skills of requirements analysis, management and communication are still critical to the success of the projects.

Operations. In the world of Operations, business analysts are often found juggling change requests, release schedules, quarterly freeze exception requests with one hand, and SOx guidelines with the other. Their managers may not think of them as business analysts, but the knowledge area of business analysis planning and monitoring applies directly.

Applications. Business and technical applications are as plentiful as mosquitoes at your picnic at dusk. A ridiculously over-simplified view of the world would put business-level applications in one bucket, and everything else in the other bucket. By business-level applications I mean those in the class of Enterprise Relationship Management systems, e.g., Oracle, or Human Resource management systems, e.g., PeopleSoft, or Supply Chain management systems, e.g., SAP, or Customer Relationship management systems, e.g., Sales Force, and … those applications that support a business function that is specific to the type of organization, for example, many city governments use Azteca’s Cityworks. Many Business Analysts spend their entire career in one application!

Let’s look at Petra’s situation. Her most recent experience is five years of experience doing release management. Prior to that she had two years of application change request management as an entry level BA. She has been the release management team lead for the past year and after that very long year the job is no longer an interesting challenge. Petra is worried that she has become pigeon-holed in her job, that is, her manager assumes she’ll do release management forever. Petra knows the operations angle of her job very well, but she hasn’t ever worked on a business case, she has never done a solution assessment, let alone worked on a cross-functional strategic initiative. She’s really good at release management and she knows these skills would transfer well to another company. Should she branch out or should she stay focused in this one area?

She looks at her company’s job postings and sees one in the Network operations group. They need a business analyst with requirements management skills and some PM experience. She has no infrastructure experience at this point in her career, should she apply for the job?

There’s no right answer – only more questions to be asked – chief among them is whether she is interested enough to explore this new area. Some companies have good Human Resource staff that can ask her questions to help her make a decision. Petra can also talk to her manager about career development – a good manager is willing to help. She could also talk to the manager of the network project to find out if she might be a good fit. Maybe this isn’t the right project, but there will be others. And, it will give her current manager time to plan a transition. Talking to her colleagues can also be helpful – they may know of even better opportunities for what they perceive her strengths and interests to be.

Truth be told, I have a bias towards developing a broad base, I think that a wide range of experience gives a BA a qualitatively better perspective to assess risk and benefit. You could argue that while I’m a generalist business analyst, that is, I have no expertise in any applications or infrastructure technologies; I have also specialized in being a generalist. In the same breath, I could argue that a Finance BA who systematically becomes proficient with every module in Oracle ERP is a person who has generalized specialist skills in a single application.

There’s plenty of wiggle room in the specialist – hybrid – generalist model, which is one of the beauties and aggravations of Business Analyst position. There’s more to job-hunting than just responding to job postings and shaking down your LinkedIn network for leads. Think about what you want from your career, what you are curious about, what skills and experience you want to acquire to make yourself the right BA for the jobs that interest you as well as the right BA that the hiring manager is hunting for.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

Cecilie Hoffman’s professional passion is to educate technical and business teams about the role of the business analyst, and to empower the business analysts themselves with tools, methods, strategies and confidence. Cecilie is a founding member of the Silicon Valley chapter of the IIBA. She authored the 2009 Bad Ass BA series for BA Times and most recently the poem, A is for Analysis. See her blog on her personal passion, motorcycle riding, at http://www.balsamfir.com. [email protected]