Off-shore vs. On-shore in the development space

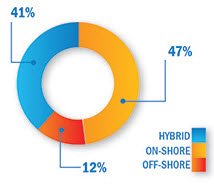

Off-shoring development and other IT services has been an increasingly popular trend over the past decade, with many of the Fortune 500s deciding to outsource their more technical services to emerging markets, where set up costs and pay scales were much lower. Although initially attractive, these seemingly lower costs are by no means “no strings attached” and many companies are finding the hidden costs incurred in the medium-to-long term far outweigh the initial savings. Cost is not the only factor to consider with regards to off-shoring development. Other important factors include cultural and experiential misalignment and time zone differences, which, especially when coupled with language barriers, can severely hamper communications.

Off-shoring development and other IT services has been an increasingly popular trend over the past decade, with many of the Fortune 500s deciding to outsource their more technical services to emerging markets, where set up costs and pay scales were much lower. Although initially attractive, these seemingly lower costs are by no means “no strings attached” and many companies are finding the hidden costs incurred in the medium-to-long term far outweigh the initial savings. Cost is not the only factor to consider with regards to off-shoring development. Other important factors include cultural and experiential misalignment and time zone differences, which, especially when coupled with language barriers, can severely hamper communications.

Effective communication is perhaps the most critical factor in ensuring the success of a development project. Without being able to communicate their requirements to a development team, customers are almost guaranteed not to get what they had hoped for, which can lead to expensive pieces of software being entirely scrapped. The same is true for adjustments in scope or changes in requirements. As we all know, the business world is in a constant state of flux and if the development team is located thousands of kilometres away, in a different economic climate, with vastly different influencers, their ability to adapt is significantly undermined. Similarly, in an Agile Development and Scrum environment constant customer and user feedback is imperative to creating software that works. If the development team is not able to understand the feedback, they’re unlikely to implement the changes effectively. All of this leads to longer development cycles because the initial brief, changes in scope and requirements, and feedback on development stages are not effectively communicated, which ultimately means additional costs to the customer. It is possible to mitigate this, to some degree, by installing a local project manager on site to oversee the development. Although in most instances this is not a possibility for the customer.

Off-shoring development projects often means that the bulk of the development work will be done in a different time zone. Although in South Africa we are better positioned than US-based companies to deal with development houses in India, the Far East and Eastern Europe, where much of the off-shore development takes place, there are still challenges around effectively communicating across time zones. Setting up feedback sessions can be tricky, particularly with stakeholders for multinationals being distributed globally. There is usually at least one party who will be joining the discussion in the middle of the night, which is generally not the peak time for productivity. Similarly, time zone distribution implies a cultural distribution, which reinforces the barriers to communication formed by language proficiencies or the lack thereof with many off-shore developers. Software development is organically a collaborative process, but one can’t expect off-shore developers to fully comprehend one’s objectives, requirements and the scope when they’re coming from a different cultural context. Even with the most detailed requirements documentation, it is possible for developers to entirely miss the mark because of these factors.

If putting together and effectively communicating the requirements and scope of a project with an off-shore development team is considered to be a challenge in itself, then managing and maintaining the quality of that project escalates the challenge to the next level. Customers are often lulled into a false sense of security by the portfolio of work development houses list, but in most cases these builds were done by an elite team of developers and, in all likelihood, not the team that will be assigned to the customer. This, especially when combined with what has been termed “misaligned tertiary systems” creates numerous quality assurance issues for the customer.

The expectations a customer has when considering a developer with a degree in the relevant field, in most cases, is very different to what they actually get. This may be because the industry is relatively infantile in countries where many off-shore development houses are based, which brings with it another set of challenges. Inexperienced project managers, developers and team leads are put in charge of projects vastly beyond their capabilities, which leads to poor demand and project management, which in turn leads to lengthened development cycles and decelerated delivery timelines. All of this, once again, ultimately increases the cost to the customer. One must look at it from a strategic sourcing point of view: is it worth the cost and risk in the long-term, especially for a once-off project?

When Off-shoring Works:

Although there are many challenges that must be addressed, off-shoring development can be successful in certain situations. Research conducted for Utrecht University in the Netherlands has shown that off-shore development projects were more successful when development and stakeholder teams were smaller (Fabriek, et al, 2008), and therefore worked more closely with one another. This stands to reason, especially when following an iterative, interactive approach, like Scrum. Other factors that contributed to increased success rates for off-shore development projects include the duration of the project, the organisational complexity of the stakeholder organisation, whether or not development teams had previously worked together on projects and the geographical location and cultural similarity of the off-shore destination. Projects that were completed within a 9-month development cycle tended to show higher rates of success than those which exceeded the 9-month cap (Fabriek, et al, 2008). Similarly, stakeholder organisations with fewer than 5 stakeholder groups had more success with off-shoring their development requirements (Fabriek et al, 2008). One could argue that this is due to reduced inputs from potentially opposing points of view – the less people you have to make happy, the easier it is to ensure general happiness. The complexity of a project similarly affects success rates when considering off-shoring; the more complex a project, the higher the failure, or non-success, rates when off-shoring. Another important factor is the scope of that project – not only the complexity thereof, but how accurately the scope has been defined and how likely it is to remain static throughout the development cycle. In projects where development teams were experience with working together there was a dramatic increase in success rates (Fabriek, et al, 2008). This could be put down to individual developers having a better understanding of their colleagues’ capabilities, strengths and growth areas. An understanding of this would ultimately lead to a more successful team.

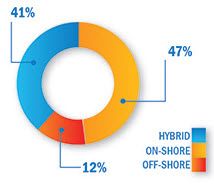

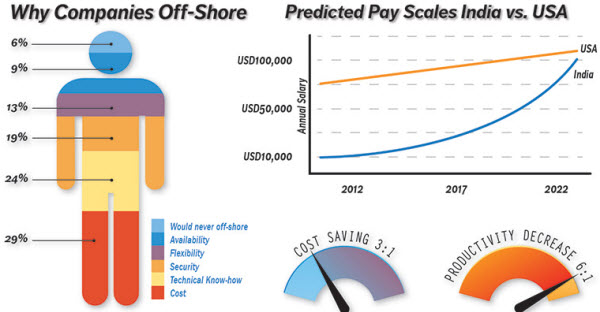

The definition of what constitutes an “off-shore” development location versus a “near-shore” development location is somewhat loose and may not be immediately clear to many stakeholders and decision makers. What is important to consider when choosing an off-shore or near-shore development partner is not necessarily the geographical distance between the two countries but rather the cultural and temporal differences. The more closely aligned a country is, culturally, the more likely you are to have your message clearly understood by your development partner. Similarly, if the country you choose to off-shore your development to is only removed by one or two time zones, you are less likely to run into planning and development issues because of delayed feedback and lengthened response times. A third option that many decision-makers neglect to consider is an in-house approach, where the organisation chooses to allow their internal development teams to develop the project. In organisations where a dedicated in-house development team is not part of the staff complement, depending on the duration and complexity of the initial project and the ongoing support requirements, an organisation may choose to bring the necessary staff onto its permanent pay-roll. This, of course, has challenges and benefits of its own, most notably the up-front cost of hiring, or up-skilling the necessary staff and the cost of the required infrastructure and technology. Benefits of bringing the development team in-house is that an organisation will now have dedicated resources working full-time, to its timelines, on the project.

Conclusion:

The combination of ineffective communication due to language, time zone and cultural barriers; unpredictable team dynamics and ineffective project management; and misaligned standards in terms of education and experience makes project management from the customer’s perspective increasingly difficult with off-shore development projects. In many instances off-shore development projects were only successful in respect of scope and quality, but often took much longer than anticipated and therefore cost the customer significantly more than originally planned. The discrepancy in anticipated cost and actual cost is most often accounted for by the opportunity cost associated with the project. This can include the cost of travel to and from the country in which the development house is based, cost of communication in terms of video conferencing, online and telephonic communication, as well as the time cost associated with the project’s roll-out. Time costs include the physical time taken to complete the project, especially if it runs over deadline, as well as the time high-level stakeholders are required to spend on the project to ensure its success.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.