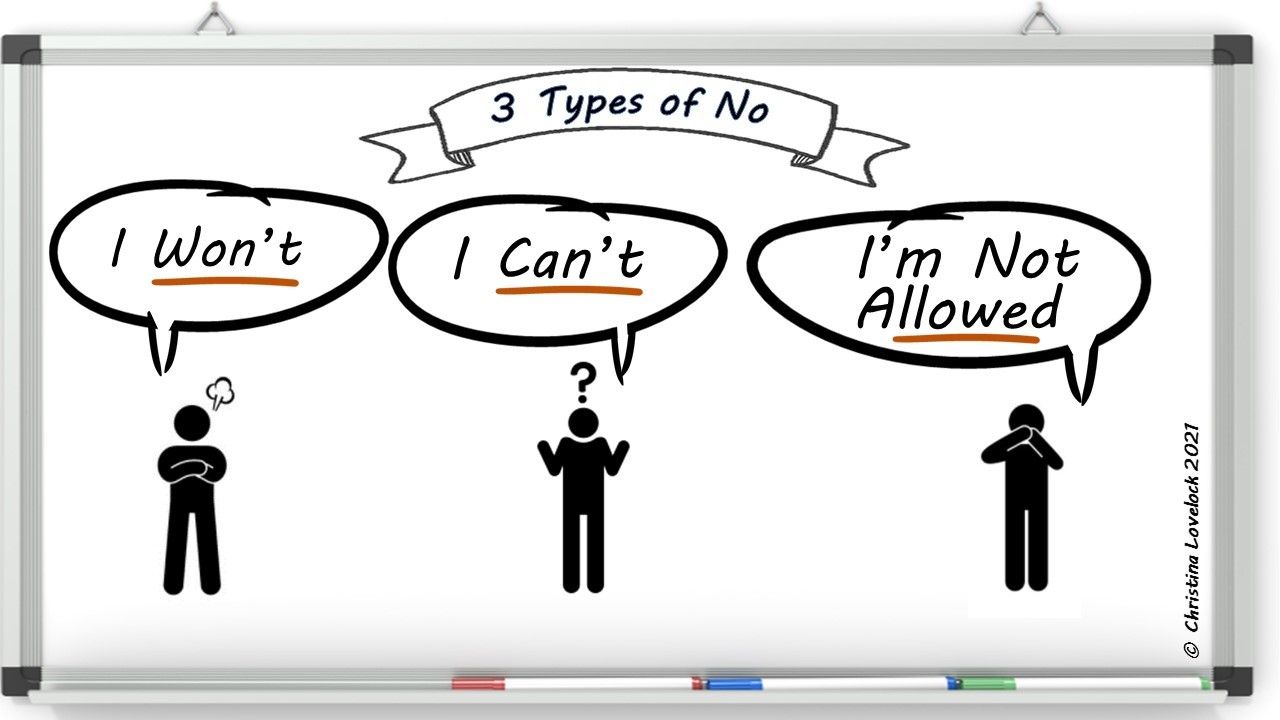

Change Resistance: 3 Types Of No

People say ‘no’ to us all the time. This can seem very final, a total unwillingness to engage.

Understanding which type of ‘no’ we are hearing can help us to avoid labelling people as ‘resistant to change’, and promote more effective engagement.

Resistant To Change

Change professionals can forget how hard it is to change. Organisations enter into seemingly un-ending change programmes, restructures and transformations. For those whose job is not part of this change industry, all of these well-intentioned initiatives feel like a distraction from ‘real’ business objectives and personal goals. So, as change professionals, we hear ‘no’ a lot. It comes it lots of forms such as “No one is able to attend that workshop”, “It is not possible to release anyone for the project team” and “We’re too busy”.

It is not possible to conduct business analysis or achieve any kind of change without other people. We need their input, we need to ask questions, we need them to engage. When they are unwilling, we can be quick to label them as ‘resistant to change’.

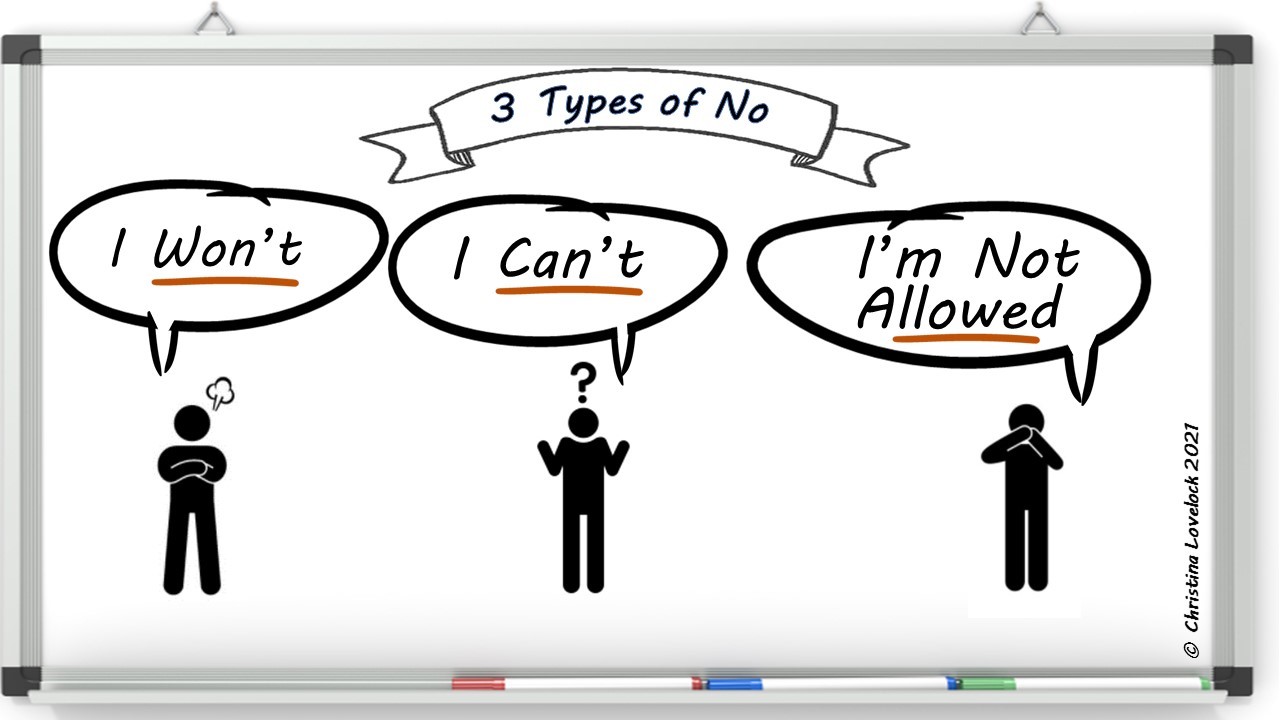

The Three Types Of ‘No’

People often avoid actually saying no, and they certainly avoid giving their real reasons and motivation for doing so.

I Can’t

This usually comes down to either capability or capacity. I can’t help you because:

- I don’t know how

- I don’t have time

- I don’t have anyone available

- I don’t have the tools/knowledge/data required

- I don’t have the budget

This can be a helpful type of no, because it may reveal incorrect assumptions or the lack of knowledge or resources. It may also provide sign-posting to the best-next-step or person who does have what is needed. If there is willingness to help, but practical issues make it a ‘no’… this can be useful too. Creating a conversation which adds “yet” to the and of all the above statements changes the narrative. It becomes a discussion about planning: obtaining funds or resources, scheduling work, obtaining information.

I’m Not Allowed

There may be real or perceived barriers to saying yes – in the form of ‘permission’ concerns.

This can include:

- That’s not part of my role/job description

- My manager doesn’t want me to

- I don’t have access/authorisation

These types of restriction may be real – in which they can be investigated and challenged to understand if they are still relevant or a product of historic decisions, assumptions and preconceptions. If they are perceived limitations, they can also be explored and challenged. Again, if there is a willingness to help many of these blockers can be overcome, the first hurdle is to identify them!

I Won’t

The trickiest type of no is one which is underpinned by unwillingness to help. This can be fuelled by issues such as:

- I don’t want too

- I don’t agree

- I don’t like you/the project/the work

Control is a major factor in whether we enjoy our work or not. People sometimes refuse to engage in one area as a reaction to a lack of control in another. Change initiatives often see education about the change as the way to overcome resistance. “Sell the benefits!”, “Explain what’s in it for them!”…

Listening rather than telling may be the best way forward from an “I won’t”. Be genuinely curious, try to see their perspective and try to address concerns and barriers. Not everyone will be convinced or motivated to be involved. Decided how much time and energy can by spent on one person.

One ‘No’ Disguised As Another

The most socially acceptable and ubiquitous type of no is “I am too busy”. This is an “I can’t” statement. When we reframe this as a question of priority as opposed to time, it can help to move the conversation forward – however “too busy” maybe a stalling tactic, where the underlying no is really: I won’t.

If attempts at tacking the question of priority, and addressing potential scheduling options do not work, then the underlying cause is not really time. Handling this honestly and openly, looking for the common ground or areas of potential compromise may help. If all else fails consider escalating appropriately, but this should not be the first thought.

Conclusion

For people to say “yes” to our many requests for input and engagement they need three things: capability, capacity and motivation.

Appropriate and proactive training and development, planning, and communication clearly have significant roles to play in ensuring these three things are in place. However, at a human and day to day level, we can all try to understand the “no” we are hearing, and work with that person professionally and compassionately to achieve the best outcomes for our organisations.