To-Do List/Ta-Da List

Being organised is an important aspect of business analysis, and so is personal reflection and maintaining motivation.

How can these aspects relate to each other?

To-do lists, whether mental, physical or digital (or a combination of all three!) form a key part of our strategy for ‘getting things done’, prioritising and feeling ‘on top of things’.

There is a sense of satisfaction in completing a task, and literally checking things off. That good feeling can be very fleeting, as we look with dismay at the many items remaining on the list, and we tend to take no time to reflect on the totality of things that have been checked-off.

A fact of modern life is that you will never reach the end of your to-do list!

Perhaps there is a way to maintain that sense of accomplishment, to create a lasting record of achievements and have somewhere to turn when a boost of motivation is needed.

When something is completed from your to-do list, take a couple of extra seconds to see if this should be moved to your ‘Ta-da’ list.

This may not be the ‘big-ticket’ items we can put on a CV, but the day-to-day activities we are getting through and instantly moving onto the next task. Items on the Ta-da list might include:

The positive things:

- That was great

- I surprised myself

- I enjoyed that

- I’m proud of that

- I got great feedback.

The challenging things:

- I thought it would take ages but it didn’t

- I’ve been putting it off

- I’ve never done it before

- I was dreading it but it was fine

- I was outside my comfort-zone, and I had to really push myself

- It didn’t work out how I imagined, but I learned something.

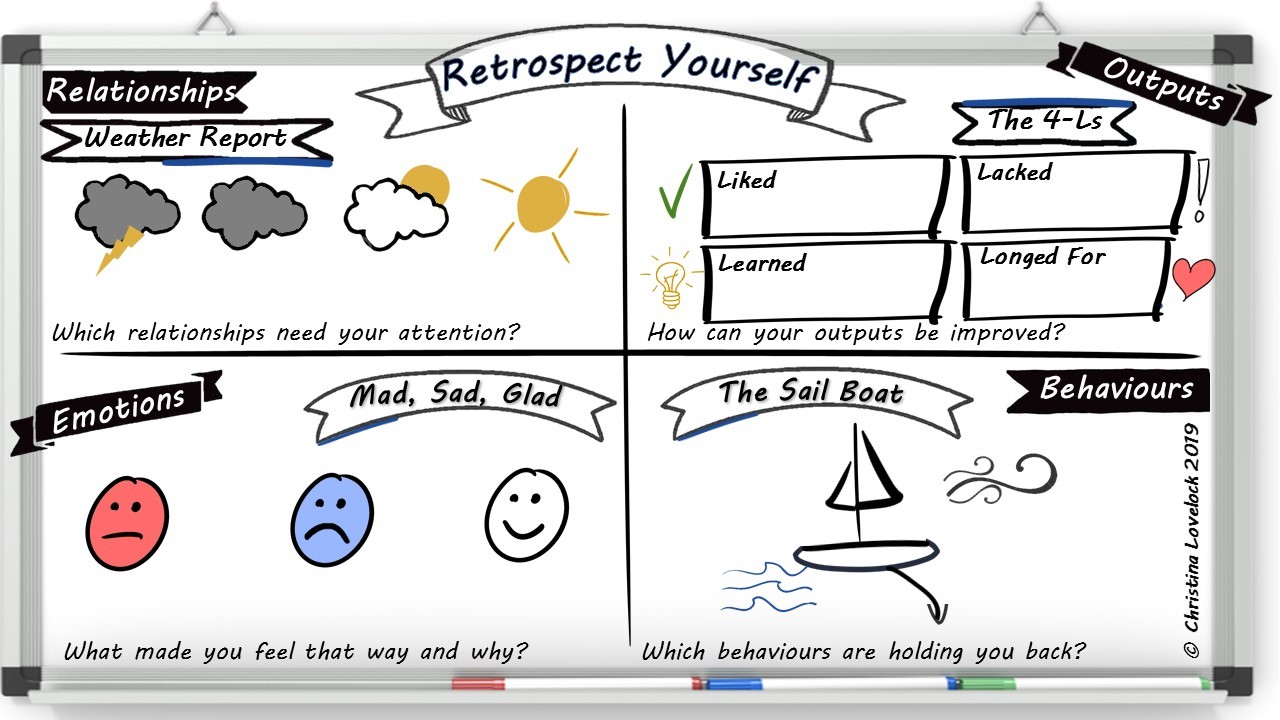

The people things:

- We worked really well together

- I have a good relationship with that person now

- I managed to influence that decision

- I really helped that person

- They really helped me.

The list may not turn out to be things you can easily articulate as achievements to other people (new job/promotion/bonus/award…) but will grow into a record of everyday activities and successes which would have been all too easily forgotten.

Manging to take note of even one item per month will yield a motivating list to look back on.

EXTENSION TO KANBAN

A physical or digital Kanban board gives us a shared record of what has been ‘Done’. This is a neutral list which does not draw attention to the things the team agree are the major achievements, these achievement’s may or may not reflect particularly significant or interesting features. Extending Kanban to include ‘Ta-da’ moments keeps a celebratory list of the hurdles overcome, the good decisions made and the results that are achieved when the team is at its best.

CONCLUSION

In knowledge based and digital roles, it can often feel that all we ‘achieve’ day-to-day is meetings and emails. To keep up our motivation we need to record and reflect on our wins, successes and feel-good moments throughout the year.

As the year comes to a close, and we enter the new year with resolutions and good intentions, consider how you can make personal reflection part of your routine, as high up on your to-do list as being organised.

Further reading: Gretchen Rubin, Better Than Before (2016)