Last month, we talked about Requirements Definition for Outsourced teams. In this article, we are going to explore a new dimension to requirements definition challenges that looks at the reality of today’s distribution of departments, personnel, and company locations. While there have been many drivers behind today’s distributed workforce, much of it has been driven by the record number of mergers and acquisitions in the past five years. IT teams are finding it “normal” to engage with peers and internal customers located in different buildings or even in different time zones. Gathering and defining requirements can be quite a challenge in this environment.

Automating and Empowering Critical Business Processes

Today’s business application software is relied on to automate and empower critical business processes. There is not an organization in the developed world that can process a sales order, hire an employee, or close their book at the end of a fiscal year without the help of business software. Software is not an accessory to the business, it is the business.

In today’s software development landscape, project teams are consistently being stretched to deliver against increasing business challenges to enable an organization to sharpen their competitive advantage. In a global market place, this continual pressure on IT is not just stretching team capacity; it is actually stretching the organizational structure as well. In fact, in 2009, over 70% of business and IT teams are geographically distributed and globalization is the business driver for the majority of new projects [1].

With geographical distribution becoming the standard operating procedure, collaboration between business and IT teams around project requirements has become a new focal point to control project team efficiency and effectiveness. Organizations must improve the fidelity and precision of their software requirements to ensure that IT delivers the right solutions that the business needs. Communication of project requirements must evolve to eliminate the cultural, geographic, and time-zone barriers that now exist between these separated colleagues.

This article explores how software projects are improving the collaboration between distributed IT and business teams by focusing on requirements communication. We will explore how visual requirements simulation plays a critical role to ensure understanding and to eliminate barriers to productivity that naturally exists within distributed, global teams.

Requirements Analysis: Becoming More Complex

Requirements are the blueprint to the functionality, interoperability, and integration of business software. As more organizations drive to streamline, consolidate, and modernize existing applications, the complexity of requirements is increasing. Analysis of requirements has become a job within itself, with an emerging dedicated stakeholder that services the development and communication of project requirements to business and IT stakeholders. This stakeholder is commonly referred to as the business analyst or business systems analyst.

As the world continues to get smaller and businesses expand to reach new markets and lower-cost suppliers, globalization has become a major driver of IT projects. In 2009, the majority of IT projects are designed to assist businesses scale to meet the needs of globalization. According to a recent CIO survey by Smart Enterprise on Globalization and IT, over 50% of IT teams are being asked to build systems for non-US supply chains, 40% are being asked to deliver software applications that leverage third party technology service providers and 60% of new projects are serving customers in a different country.

On top of the increasing complexity of IT projects driven by globalization, team distribution has become a critical operational challenge. According to a recent report from the IEEE, “key risk factors associated with IT development projects are magnified or multiplied when dealing with distributed project teams.” Distributed teams are largely in place due to business impacts from globalization. Typical drivers include the increase in mergers and acquisitions, the need for new talent pools, the leveraging of lower-cost resources, outsourcing, and overall business geographic demand. According to the IT Strategy Center, the most significant impacts of distributed teams are directly related to communication of business context, the implementation of language barriers, time zone separation, the lack of physical exchange, and the reliance

on batch oriented communication.

CIOs can adopt new requirements definition practices and techniques to appropriately eliminate the risk associated with distribution. These practices include shifting away from the heavy use of natural language expression and moving toward the use of multi-aspect requirements definition with visual simulation and validation. Multi-aspect requirements definition enables organizations to standardize on rich requirements that eliminate ambiguity and imprecision that often exists in the geographic separation of teams.

Levels of Geographic Distribution

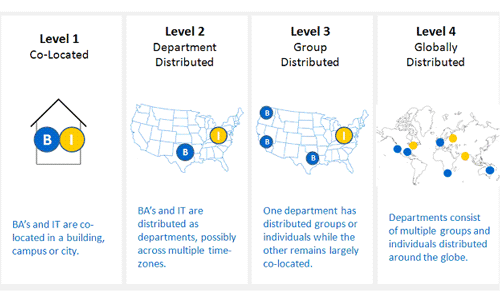

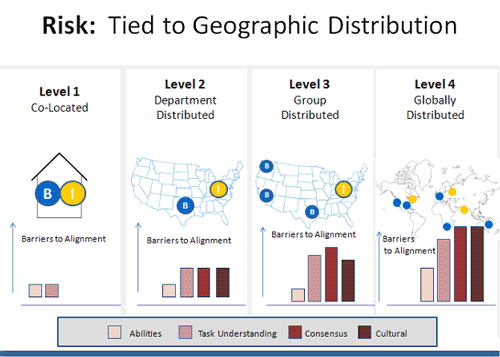

My company’s customers range across four distinct levels of team distribution. Each level creates a unique set of challenges for defining and communicating project requirements. Figure one illustrates these four levels of distribution.

At level one, business and IT teams are co-located within the same building and location. Just ten years ago, this was more common than any other level, but in 2009 this represents less than 30% of Fortune 500 IT teams. At level two, business and IT teams are distributed at a department level. IT is usually centralized and acts as a service arm to the business. At level three, business teams themselves, or IT teams themselves, are geographically separated, which increases the complexity and challenges of inter-department collaboration. Finally at level four, globalization has created the ultimate geographic challenge, with team separation and distribution pervasive across the globe. With globalization and the rise of outsourcing, this has become all too common.

Figure One: Four Levels of Team Distribution

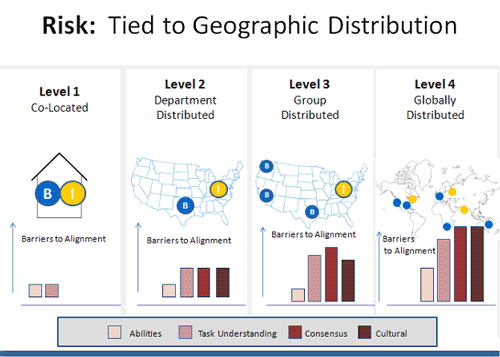

As organizations evolve to embrace more distribution, the challenges to understand the context of application requirements increase significantly. These challenges include intra-teams functional capabilities, task understanding, gaining organizational consensus, and the cultural challenges to understanding. In Figure Two, we overlay how these challenges (and risks associated with them) increase significantly as teams become more distributed.

Figure Two: Challenges to Alignments of Distributed Teams

Challenges of Requirements Communication with Distributed Teams

As we discussed in the previous section, geographic distribution injects new challenges to IT productivity and alignment. Requirements communication fits squarely into the center of the challenges of distributed teams. Traditional methods of communicating requirements, which include enumerated lists of features, functional and non-functional requirements, business process diagrams, data-rules, etc., generally are documented in large word-processing or spreadsheet documents. When applied to distributed teams, this method of communicating requirements creates significant waste and opportunities for failure, as the barrier to understanding can become too great to overcome. Incorrect interpretation and the lack of requirements validation can create artificial (or false) goals which consume valuable team resources. Due to the nature of software development, these false goals usually manifest themselves into incorrectly implemented code, resulting in costly waste and rework.

Outsource providers often treat such rework as change, resulting in costly charge-backs to the business.

Multi-aspect Requirements Definition for Distributed Teams

To significantly reduce the probability of ineffective requirements communication through natural language documentation, IT organizations are transitioning to more precise vehicles to communicate requirements. One of these vehicles is the adoption of the multi-aspect definition approach to communicate requirements in a highly visual way. Multi-aspect definition provides detailed context capture through highly precise data structures. These definition elements used in these holistic representations include use-cases for role (or actor) based flows, user-interface screen mockups, data lists, and the linkage of decision-points to business process definitions. These structures augment enumerated lists of functional and nonfunctional requirements.

The benefits of this approach include the use of simulation to ensure requirements understanding. Simulation is a communication mechanism that walks requirements stakeholders through process, data, and UI flows in linear order to represent how the system should function. Stakeholders have the ability to witness the functionality in rich detail, consuming the information in a structured way that eliminates miscommunication entirely.

Multi-aspect definition and simulation also provide context for validation. Validation is the process in which stakeholders review each and every requirement in the appropriate sequence, make appropriate comments, and then sign-off to ensure the requirements are accurate, clear, understood, and are feasible to be implemented. Requirements validation can be considered one of the most cost-effective quality control cycles to ensure team understanding. Since requirements are the “blueprint” of the system, distributed stakeholders can make use of multi-aspect definition and simulation during implementation to gain understanding of the goals of the project. Simulation eliminates ambiguity by providing visual representation of goals which, in turn, eliminates interpretation.

Rich requirements documentation often is a specified deliverable for most IT projects for various reasons that include regulatory compliance (Sarbanes Oxley, HIPAA, etc.), internal procedural specifications, and other internal review cycles. Multi-aspect definition can serve as the basis of this documentation and next generation requirements workbench solutions (such as Blueprint Requirements Center) can transform models into rich, custom Microsoft Word documentation. Since these documents are auto-generated, the amount of effort required to build and maintain these documents is minimized.

The Solution: A Case Study

PAREXEL is a world-leader in biopharmaceutical research. Some of the world’s largest drug, biotech, and medical device firms make use of their clinical research, consulting and medical communications services. PAREXEL was in the early stages of a major $1.2M upgrade to their revenue forecasting system. This project involved project staff distributed across many countries. They were already using HP Quality Center for requirements management test planning and management. At this early stage in the project they were already noticing issues with the requirements they had defined. General observations were that the requirements were too ‘wordy’ and abstract. Clarity had been lost in the translation of original business need into system functional requirements, and there were numerous instances of misunderstanding and misinterpretation of the requirements which, to that point, had been expressed using flat-file documents. During this early phase they took the opportunity to evaluate tools that might help with these requirements issues. Blueprint was one of the products considered and was ultimately chosen partly due to its capabilities to support distributed requirements definition teams.

The development results of the very first module defined using Blueprint Requirements Center was enough to extend its use to all enhancements of PAREXEL’s financial applications. The first module defined using Blueprint Requirements Center saved three months of rework effort.

The full extent of Requirements Center’s feature set is now leveraged to span the complete requirements lifecycle including requirements lists, use case models, user interface mockups, simulations, and the generation of assets automatically, such as tests and documents.

PAREXEL has established a corporate Blueprint forum and knowledge base and is currently in the process of expanding use of Blueprint Requirements Center to other departments throughout the organization.

Matthew Morgan is a 15 year marketing and product professional with a rich legacy of successfully driving multi-million dollar marketing, product, and geographic business expansion efforts. He currently holds the executive position of SVP, Chief Marketing Officer for Blueprint, the global leader in Requirements Lifecycle Acceleration solutions. In this role, he is responsible for strategic marketing, partner relationships, and product management. His past tenure includes almost a decade at Mercury Interactive (which was acquired for $4.5B by HP Software), where he was the Director of Product Marketing for a $740 Million product category including Mercury’s Quality Management and Performance Management products. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Computer Science from the University of South Alabama. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Computer Science from the University of South Alabama.