Three Tips for Solving the Communications Dilemma

Recently I talked to a colleague with a communications dilemma. She wondered how she should communicate with her various stakeholder groups. Thinking out loud she pondered, “When I’m with business people, I always try to use business language, including their acronyms, which I’ve gone out of my way to learn. But what about when I’m talking to the technical experts? Should I talk techie to them?” She went on to say, “I write a lot of proposals. I have some stakeholders who let me know right away about typos or if my grammar is not exactly right. I have other stakeholders who have told me that my writing style is too formal and that I shouldn’t use such correct grammar. They feel it’s intimidating and unfriendly.”

As BAs and PMs we know we’re supposed to be good communicators, but what exactly does that mean? We are trained to be aware of others’ communication style. We use our intuition, empathy, and awareness of body language to “read” others. But is that enough? And does that apply equally to our written and our verbal communication? What about the language we use? I have always loved the quote from the poet William Butler Yeats, “Think like a wise [person] but communicate in the language of the people.” Does that mean, however, that when we are talking to someone who misuses the language, that we should match our language to theirs? I don’t think so. Matching the communication style does not necessarily mean mimicking their language. However, we do want a communication style that makes our stakeholders comfortable.

How can we solve this communications dilemma? Here are three tips for both written and verbal communications that can help.

- Take the time to keep it simple. We are all aware of the wisdom of keeping it simple, but simple doesn’t mean easy. Simple doesn’t mean careless. It is often harder to keep it simple, because keeping it simple requires thought, precision, and a good command of the language. I find that it takes a great deal of thought to write concisely and say everything I want to in language that all stakeholders will understand.

That same principle of simplicity applies when we paraphrase, or restate what was said in different words while keeping the nature of what was said intact. I think paraphrasing is one of the most difficult skills to master. It requires the ability to take in a lot of information, to synthesize it, to concentrate on what is being said, and at the same time to rework the ideas to make them understandable. It’s tough work! - Be correct without being pretentious. When we use incorrect grammar or when we don’t bother to check our work, we run the risk of being judged poorly, of reducing our credibility, and of not being taken seriously. On the other hand, when we use ornate language and complex sentence structure, we run the risk of losing our audience. I remember taking a multiple choice test in high school where the correct answer was “It is I who am going shopping.” Wow. And of course there’s the famous line from Churchill. Apparently his editors rewrote a sentence to make it grammatically correct, and apparently he responded with the famous line, “This is the sort of bloody nonsense up with which I will not put,” pointing out the ridiculous nature of obscure grammatical rules. In a nutshell, I think we should strive for communications that are both intelligent and clear.

- Use language that both technical and business people understand. I have found that when I use technical language with business people, they have a harder time understanding me than if I use business language with technical people. Using business language, then, tends to be more easily understood by all stakeholders. As a project manager working on software development projects, I always encouraged the developers to use business terms, even when the subject was technical in nature. For example, instead of saying DB17, I encouraged the team to talk, even among themselves, about the Price Change database.

Another example I use is that when we need to find out about data business rules, we might walk into a requirements workshop and ask about the cardinality and optionality, but we’d probably get some blank stares. However, we can translate those concepts into questions our SMEs can understand and answer. For example, we might ask if end-users can set up customers who don’t have any accounts. Or what information the end-users need to enter before they can leave the web page. I have always believed that translating technical concepts into business English, while annoying to some team members and technical whizzes, has always been worthwhile. It encourages us to focus on the business need rather than the technical solution.

Finally, let’s look at the intent of the communications. If we all understand each other and what we’re trying to say, then I believe we are communicating effectively, even if our grammar isn’t perfect or we don’t use the right words. And I believe that most stakeholders get that and won’t judge us harshly. However, for those stakeholders who want each “i” dotted, let’s proof our work. It will help build our credibility. The key is to know our stakeholders, but that’s a topic for a different day.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below!

The “Bad” BA or PM. Is there such a thing, I wondered, when our editor asked for blogs on this subject? In giving it some thought it seemed to me that there may not be any bad business analysts (BAs) or project managers (PMs), but there certainly are some bad BA and PM practices. I’ve compiled a list of some of my favorites. As an aside, some of the worst BA/PM behavior occurs when the relationship between these two critical project roles struggles. In this blog I address bad BAs, bad PMs, and bad BA/PM relationships.

The “Bad” BA or PM. Is there such a thing, I wondered, when our editor asked for blogs on this subject? In giving it some thought it seemed to me that there may not be any bad business analysts (BAs) or project managers (PMs), but there certainly are some bad BA and PM practices. I’ve compiled a list of some of my favorites. As an aside, some of the worst BA/PM behavior occurs when the relationship between these two critical project roles struggles. In this blog I address bad BAs, bad PMs, and bad BA/PM relationships.

OK, you Stieg Larson fans, I’m not Lisbeth Salander, the heroine of the best-selling trilogy. I have neither her wits nor her strength. But I have kicked a few hornet’s nests in my career. Some of these nests were full of angry hornets and some full of non-aggressive bumblebees. However, every instance reinforced the importance of doing the right thing for the organization, even if it meant getting stung.

OK, you Stieg Larson fans, I’m not Lisbeth Salander, the heroine of the best-selling trilogy. I have neither her wits nor her strength. But I have kicked a few hornet’s nests in my career. Some of these nests were full of angry hornets and some full of non-aggressive bumblebees. However, every instance reinforced the importance of doing the right thing for the organization, even if it meant getting stung.

The following is an excerpt from the book

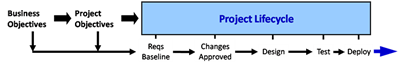

The following is an excerpt from the book  Figure 1 – Backwards Traceability

Figure 1 – Backwards Traceability  Figure 2 – Forwards Traceability

Figure 2 – Forwards Traceability