Read All About It – Why Reading is a Critical Skill in BA

I love reading.

It is to the point of compulsion where I log into my Amazon.com account and sneak in a couple titles

of varying degrees, regardless of what my original intention was. I always mutter a friendly curse

towards the algorithms that market new, old, debut and longstanding authors of novels, novella, and

fantastical stories each time I log in. It is not just limited to online…oh, no, not at all. Traveling, locally,

domestic, or internationally? Same problem. I make it a significant point to dop into any local

bookstore with self-guaranty that I will walk out with, at minimum, one book, genre notwithstanding.

Reading, however, has become so much more than just “getting lost in the story” or falling in love with

characters whom we can only dream to meet, mirror ourselves against or become attached to. It is not

a hobby, it is not just a compulsion, it is not habit. It is something else, something more: a skill. A

critical skill, at that. A skill that, like anything, any one can become proficient, an expert on, but

requires the same thing: practice, practice, practice. While I could spend the time writing this piece on

the top ten books a business analyst should read (and was the original idea for this article) …instead, I

make a proclamation. A quasi-Magna Carta, if you would: all business analysts must take the time in

their schedules to make room for improving this critical and formidable skill.

Today, there are rumors of studies finding that young adults after their high school (post-secondary)

education will never read a book again. It is flabbergasting on one hand, but to lose a critical skill like

reading that is sharpened when you open the cover-to-cover bound print matter (or e-book for you

digital readers), it is breathtaking. We, as business analysts, whether we realize it or not, are

consistently reading. Reading our e-mails, reading our business analyst documentation, reading

requirements. You are reading right now, are you not? That is pending that you continue to read my

piece on this subject matter. We are, in and out of varying intervals and degrees, reading! Some read

faster than others, some take the time to deeply understand and analyze what is on the paper, or page

before us. Aside from this, you are inherently practicing a critical skill in which will only make you

better, as a business analyst.

Advertisement

Google search any reason as to why human beings should read and the results are countless: whether

it be for stress relief, for better memory retention, to prevent disease, it is all relevant. However,

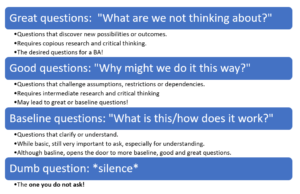

relevancy aside, it becomes relevant to our work. Reading requires us to think, to analyze, to ask

ourselves questions. Is that not what we do now? Think, analyze, ask questions? Of course, overlooking

that I am oversimplifying the business analysis method, reading leads us to business analyzing!

Reading only stands to benefit you to improve in these areas; reading helps establish connections, to

understand concepts. Who does not like conversing in the language of titles, authors and favorite quotes

from that series or book that came out last week, month, year? There once was a video game I played

as a young adult and in the conversation of movies, they spoke about how movies during their time

(when movies/cinema were in their Golden Age), help people out of a bind or jam that they do not

understand. Take out movies/cinema and replace with books/reading, and there you got it.

So, read all about it! And I do not mean that slogan about the latest newspaper (although a reliable

source for information), I truly mean…read all about it. Being able to become a fount of knowledge

and to be able to translate that knowledge into performance as a BA should be your guiding light. As

a business analyst: think about it, analyze it, ask questions about it. Understand it…you will thank

yourself someday