Fostering Team Creativity: The Business Analyst’s Sweet Spot

The 21st Century BA Series From Tactical Requirements Manager to Creative Leader of Innovative Change

The 21st Century BA Series From Tactical Requirements Manager to Creative Leader of Innovative Change

As we look ahead into the next century, leaders will be those who empower others.

—Bill Gates, American business magnate, philanthropist, author, and is chairman of Microsoft

The need for effective team leadership in the business world can no longer be overlooked. Technology, techniques, and tools don’t cause projects to fail. Projects fail because people fail to come together with a common vision, an understanding of complexity, the right expertise, and effective methods and tools. Team leadership is different from traditional management, and teams are different from operational work groups. Successfully leading a high-performing, creative team is not about command and control; it is more about collaboration, consensus, empowerment, confidence, and leadership.

Effective Teams

If a business analyst is to step up to the task of becoming a credible project team leader, she must have an understanding of how teams work and the dynamics of team development. Team leaders cultivate specialized skills that are used to build and maintain high-performing teams and spur creativity and innovation. Traditional managers and technical leads cannot necessarily become effective team leaders without the appropriate mindset, training, and coaching.

A small group of thoughtful people could change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.

––Margaret Mead, American cultural anthropologist, author, lecturer

Teams are a critical asset used to improve performance in all kinds of organizations. Yet business leaders have consistently overlooked opportunities to exploit the potential of teams, confusing real teams with teamwork, team building, empowerment, or participative management.[i] We cannot meet 21st-century challenges––from business transformation to continuous innovation––without high-performing teams who are comfortable with turning uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity into innovation.

The Power of Teams

Examples of magnificent teams are all around us: emergency responders, symphony orchestras, and professional sports teams, to name just a few. When we see these teams in action, it feels like magic. These teams demonstrate their prowess, creativity, accomplishments, insights, and enthusiasm daily and are a persuasive testament to the power of teams. Yet the business project environment, especially the IT project environment, has been slow to make the most of the power of teams. It is imperative that business analysts who aspire to develop into creative leaders understand how to unleash this great power.

New Product Development Teams

Business success stories based on the strategic use of teams for new product development are plentiful. For example, 3M relies on teams to develop its new products. These teams, led by product champions, are cross-functional, collaborative, autonomous, and self-organizing. The teams deal well with ambiguity, accept change, take initiative, and assume risks. The company has established a goal of generating half of each year’s revenues from the previous five years’ innovations and the other half from new products not yet invented. 3M’s use of teams is critical to meeting that goal.[ii]

Another success story is Toyota, despite the company’s engineering problems that led to unprecedented recalls in 2009–2010. Toyota continues to boast the fastest product development times in the automotive industry, is a consistent leader in quality, has a large variety of products designed by a lean engineering staff, and has consistently grown its U.S. market share. Teams at Toyota are led by a chief engineer who is expected to understand the market and whose primary job is vehicle system design. The chief engineer is responsible for vehicle development, similar to the product champion at 3M.[iii]

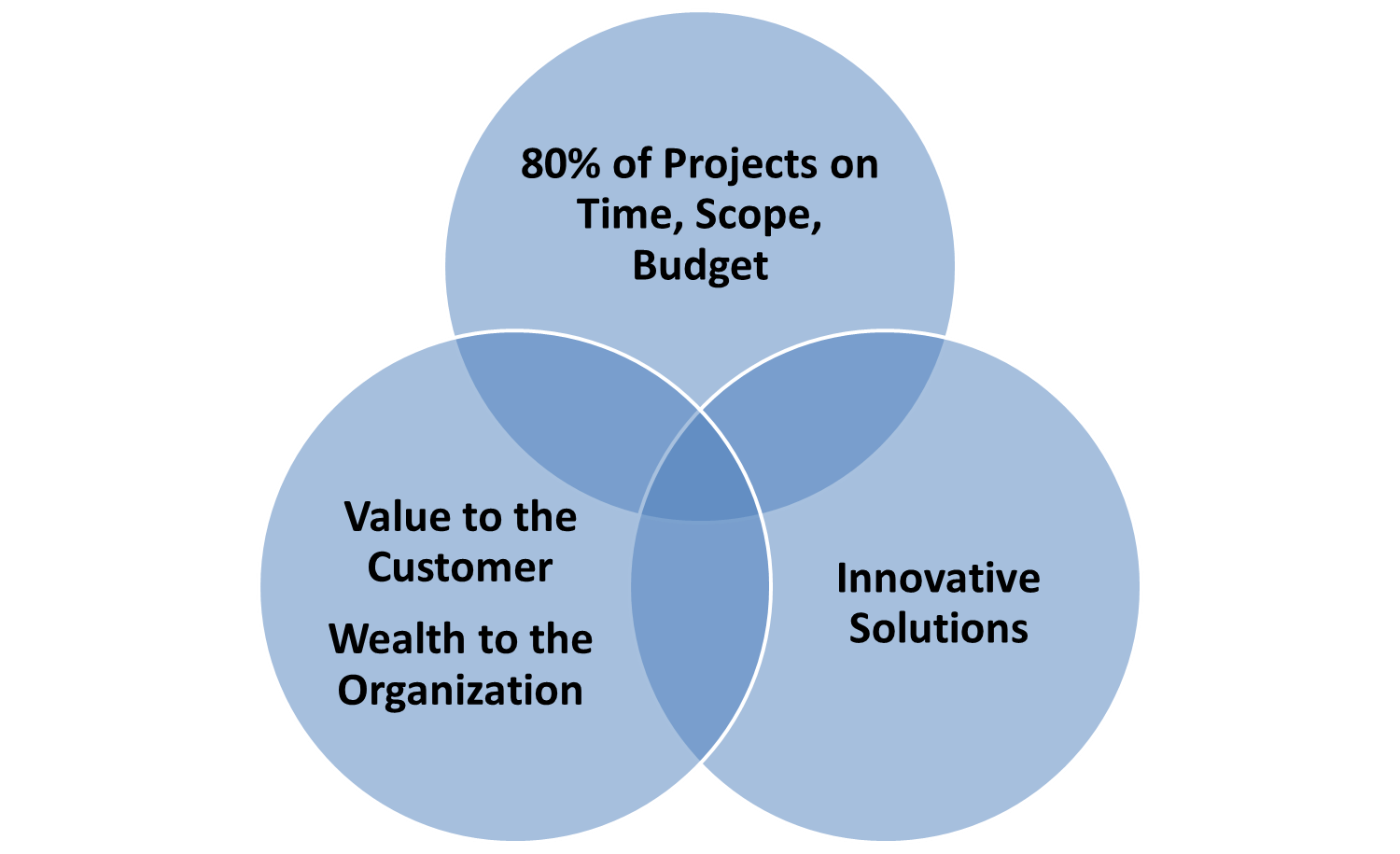

Economists have been warning us for years that success in a global marketplace is contingent upon our capability to produce products on a tight schedule to meet the growing demands of emerging markets. The same is true of projects to develop software products and solutions for business problems, to improve business performance, and to use IT as a competitive advantage. It’s not enough to deliver projects on time and within budget, and scope; it is now necessary to deliver value to the customer and wealth to the organization faster, cheaper, and better.

The Wisdom of Teams

For the business analyst who is struggling to understand how to build high-performing teams, a must-read is The Wisdom of Teams by Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith. The authors talked with hundreds of people on more than 50 different teams in 30 companies to discover what differentiates various levels of team performance, where and how teams work best, and how to enhance team effectiveness.

Wisdom lies in recognizing a team’s unique potential to deliver creative results. Project leaders strive to understand the many benefits of teams and learn how to optimize team performance by developing individual members, fostering team cohesiveness, and rewarding team results. Katzenbach and Smith argue that teams are the primary building blocks of strong company performance.[iv]

The Stages of Team Development

As a member of the project leadership team, the business analyst is partially responsible for building a high-performing team and fostering creativity and is fully responsible for building a high-performing requirements team and proposing innovative solutions. To successfully develop such a team, it is helpful to understand the key stages of team development. We use the classic team development model from Bruce Tuckman as a guide, since the Tuckman model has become an accepted standard for how teams develop.

The Tuckman Model

The Tuckman model that outlines the five stages of team development—forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning—has become the gold standard for studying team dynamics.[v]As a team transitions from one stage to the next, the needs of the team and its individual members vary. A successful team leader knows which stage the team is in and skillfully manages transitions between the different stages. The following figure depicts the typical stages of team development.

Stages of Team Development

In the forming stage, participants are introduced when the team is established and also as new members join the team throughout the project. The goal of the project leadership team in this stage is to quickly transition the individuals from a group to a team. During the forming stage of team development, members are typically inclined to be a bit formal and reserved. They are beginning to assess their level of comfort as colleagues and teammates. There is likely to be some anxiety about the ability of the team to perform, and there might be hints about the beginnings of alliances between members.

During this stage, the project manager’s job (with the support of the business analyst and other project leads) is to encourage people to not think of themselves as individuals but as team members by resolving issues about inclusion and trust. Team members may wonder why they were selected, what they have to offer, and how they will be accepted by colleagues new to them. Individuals have their own agendas at this stage because a team agenda does not yet exist. It is during this stage that the team leaders present, and give the team members the opportunity to refine, the team vision, mission, and measures of success. Allowing the team members time and opportunity to express their feelings and collaborate to build team plans will help members begin to make the transition from a group of individuals to an effective team. During this stage, team members form opinions about whom they can trust and how much or how little involvement they will commit to the project.

Storming is generally seen as the most difficult stage in team development. It is the time when the team members begin to realize that the task is different or more difficult than they had imagined. Individuals experience some discrepancy between their initial hopes for the project and the reality of the situation. A sense of annoyance or even panic can set in. There are fluctuations in attitude about the team, one’s role on the team, and the team’s chances for success.

The goal of the team leaders in this stage is to quickly determine a subset of leaders and followers and to clarify roles and responsibilities so that the team will begin to congeal. Individuals will exert their influence, choose to follow others, or decide not to participate actively on the team. For those who choose to participate actively and exert their influence, interpersonal conflict might arise. Conflicts also might result between the team leaders and team members, particularly if team members believe the leadership is threatening, vulnerable, or ineffective.

It is important to realize that conflict can lead to out-of-the-box or out-of-the-building thinking (described in Chapter 4), so the team leaders should encourage new ideas and viewpoints. For team leaders who do not like dealing with conflict, the storming stage is the most difficult period to navigate. Although the inevitable conflict is sometimes destructive if not managed well, it can be positive. Conflicting ideas, raised in an environment of trust and openness, leads to higher levels of creativity and innovation.

The job of team leaders is to build a positive working environment, collaboratively set and enforce team ground rules that lead to open communication, and gently steer the team through this stage. The common tendency is to rush through the storming stage as quickly as possible, often by pretending that a conflict does not exist, but it is important to manage conflicts so they are not destructive. It is also important, however, to allow some conflict because it is a necessary element of team maturation. If new ideas are not emerging, and if team members are not challenging each other’s ideas, then creativity is not happening.

Norming is typically the stage in which work is being completed. The team members, individually and collectively, have come together and established a group identity that allows them to work effectively together. Roles and responsibilities are clear, project objectives are understood, and progress is being made. During this stage, communication channels are likely clear, and team members are adhering to agreed-upon rules of engagement during exchanges. Cooperation and collaboration replace the conflict and mistrust that characterized the previous stage.

As the project drags on, fatigue often sets in. Team leaders should look at both team composition and team processes to maintain continued motivation among members. Plan to deliver short-term successes to create enthusiasm and sustained momentum. Celebrate and reward success at key milestones rather than waiting until the end of a long project. Continually capture lessons learned about how well the team is working together and implement suggested improvements.

During the performing stage, team members tend to feel positive and excited about participating on the project. There is a sense of urgency and a sense of confidence about the team’s results. Conflicts are resolved using accepted practices. The team knows what it wants to do and is reveling in a sense of accomplishment as progress is made. Relationships and expectations are well defined. There is genuine agreement among team members about their roles and responsibilities. Team members have discovered and accepted each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Morale is at its peak during this stage, and the team has an opportunity to be highly creative.

The performing stage of team development is what every team strives to achieve. It is difficult, however, to sustain this high level of performance for a prolonged length of time, so capitalize on it while you can. The business analyst and project manager need to hone their team leadership skills to develop and sustain this most creative stage. The best course of action for the team leaders is to lightly facilitate the work: consult and coach when necessary, encourage creativity, reward performance and achievement of goals, and generally stay out of the way.

Adjourning can be thought of in the context of loss and closure. This stage of team development can be easily overlooked, as it occurs before and during a project or phase and for a short time after a project or phase is finished. During this stage of team development, the team conducts the tasks associated with disbanding the team and, to a certain extent, breaks the everyday rhythm of their contacts and transactions.

There is some discomfort associated with this stage. Surprisingly, even people whose teams have had performance issues can experience sadness or grief during this closing stage. The project leadership team should act quickly to recognize the accomplishments of individuals and the team as a whole and to help team members transition quickly to their next creative opportunity.

Traversing the Team Development Stages

The stages of team development are very much an iterative dynamic. Any change in the makeup of a team throws the team back to the very earliest stage of development, even if for a very short time. This is due to the natural evolution of teams, the addition of new members, removal of support, or changes in roles.

The balancing and leveling of power is another constant dynamic present in teams. The shifting of practical power among the core leadership team members might cause a team to revert back to the forming stage. Although this reversion might last only a short while, it is still significant; team members will have to accustom themselves to the new order. The time spent in any of the stages subsequent to the reentry into forming can vary, but make no mistake; the team will experience storming again before regaining a foothold in the norming or performing stage.

As a member of the project leadership team, you should acquaint yourself with the cycles of team development so that you can understand what the team is experiencing and manage any changes in the team’s composition or dynamics. The following table provides a quick reference on the characteristics of each team development stage.

Characteristics of Team Development Stages

Leadership Modes through the Stagesof Team Development

There are many team development models that one can use to guide team development at any given point in the project life cycle. David C. Kolb offers a five-stage team development model that suggests leadership strategies for each stage, from the team’s initial formation through its actual performance.[6]

Each stage of Kolb’s model suggests that the business analyst and project manager continually adjust their leadership styles to maximize team effectiveness and creativity. Kolb contends that a team leader subtly alters his or her style of team leadership depending on the group’s composition and level of maturity. The seasoned business analyst moves seamlessly between these team leadership modes as he or she observes and diagnoses the team’s performance. The business analyst needs to strive to acquire the leadership prowess described by Kolb. In the following table, Kolb’s stages are matched with essential leadership skills. It is particularly important for the business analyst to know when and how to assume a particular team leadership role as teams move in and out of development phases during the life of the project.

FacilitatorKolb Team Development Model

In the business analyst’s function as a facilitator (the BA’s sweet spot), the main goal is to provide a foundation for the team to make quality decisions. When the team first comes together, the business analyst uses expert facilitation skills to guide, direct, and develop the group. Skills required include understanding group dynamics, running effective meetings, facilitating dialogue, fostering creativity, and dealing with difficult behaviors. Expert facilitators possess these skills:

- Understanding individual differences, work styles, and cultural nuances

- Leading discussions and driving the group to consensus Solving problems and clarifying ambiguities

- Building a sense of team

- Using and teaching collaborative skills

- Fostering experimentation, prototyping, emergence of many like and dissimilar ideas

- Managing meetings to drive to results

- Facilitating requirements workshops and focus groups.

To become more credible as a team leader, the business analyst ought to acquire professional facilitation credentials such as those offered by the International Association of Facilitators (IAF). IAF’s work has identified the following six areas of core competency required for certification of facilitators. Each area is defined in more detail.

- Create Collaborative Client Relationships

- Plan Appropriate Group Processes

- Create and Sustain a Participatory Environment

- Guide Group to Appropriate and useful Outcomes

- Build and Maintain Professional Knowledge

- Model Positive Professional Attitude.[7]

Mediator

Transitioning from facilitator to mediator poses a challenge for new business analysts. It requires the business analyst to refrain from trying to control the team and lead the effort. The business analyst must be prepared to recognize when conflict is emerging (as it always does in teams) and be able to separate from it to mediate the situation. Although the mediator does not have to resolve the conflict, he or she must help the team members manage it. Meditation skills include:

- Conflict management and resolution

- Problem-solving and decision-making techniques

- Idea-generation techniques.

Coach

Coaching and mentoring take place at both the individual and team levels. Coaching is appropriate when trust has been established among the team members and communication is open and positive. The business analyst as coach uses experiences, perceptions, and intuition to help change team members’ behaviors and thinking. Coaching tasks include:

- Setting goals

- Teaching others how to give and receive feedback

- Creating a team identity

- Developing team decision-making skills.

Consultant

As the team begins to work well together, the business analyst transitions into the role of consultant, providing advice, tools, and interventions to help the team reach its potential. The business analyst then concentrates on nurturing the positive team environment, encouraging creativity and experimentation, removing barriers, and solving problems. Consulting tasks include:

- Assessing team opportunities

- Supporting and guiding the team to create a positive, effective team environment

- Aligning individual, team, and organizational values and strategic imperatives

- Fostering team spirit.

Collaborator

Few teams achieve an optimized state and sustain it for long periods, because such a state is so intense. At this point, both the work and the leadership are shared equally among team members. The business analyst might hand off the lead role to team members when their expertise becomes a critical need during different project activities. Collaboration skills include:

- Leading softly

- Sharing the leadership role

- Assuming a peer relationship with team members.

Clearly, project team leaders need to understand the dynamics of team development and adjust their leadership styles accordingly. Once a high-performing team has emerged, it is often necessary for the team leader to simply step aside. The following table maps the variations in leadership modes to the two team development models we have presented.

As you plan your professional development goals, it is wise for you to include training in facilitation, mediation, coaching and mentoring, consulting, and collaborating.Mapping of the Team Development and Leadership Models

Best Team Leadership Practices for the Business Analyst

Coming together is a beginning. Keeping together is progress. Working together is success.

—Henry Ford, a prominent American industrialist, the founder of The Ford Motor Company, pioneered the development of the assembly line and mass production

The business analyst has dual team-leadership roles: (1) in general, he or she helps the other team leaders (the project manager, lead technologist, business visionary) build and sustain a high-performing project team; and (2) he or she is directly responsible for building a high-performing requirements ownership team—a team of business subject matter experts (SMEs) who take ownership of the business strategy to be advanced, the business need to be satisfied, and the business benefits to be realized by the solution. In addition, the business analyst instills in the requirements ownership team the understanding that it is their responsibility to spend enough time and energy to truly understand the business, to “think out of the building” by conducting research and analysis of the opportunity, and to collaboratively create to develop an innovative solution, as opposed to simply meeting requirements.

Who Should Take the Lead?

As a member of the project leadership team, the business analyst strives to help the team members determine who should take the lead depending on the expertise needed. For example, the project manager takes the lead during planning and statusing sessions. The business analyst leads during problem definition, opportunity analysis, solution and requirements trade-off analysis, requirements negotiation and conflict resolution, cost-benefit analysis, business requirements elicitation, solution requirements elicitation, and requirements analysis, review, and validation sessions. The project manager and business analyst may jointly lead discussions centered on issue resolution and risk analysis. The business representative should assume the lead when talking about the business vision, strategy, and benefits expected from the new solution. Then the business analyst again assumes the lead when the team is validating that the business benefits will actually be realized. Likewise, the lead architect or developer (or both) leads discussions on technology options and trade-offs. The challenge is for the core leadership team to seamlessly traverse through the leadership hand-offs so as not to interfere with the balance of the team.

The Requirements Ownership Team: A 21st Century Imperative

The business analyst’s leadership role undoubtedly involves forming, educating, developing, and maintaining a high-performing requirements team and keeping the team engaged throughout the project. The first task is determining the appropriate business and technical representatives needed to navigate through the requirements activities, then securing approval to involve them throughout the project. This is no small task, since business teams are accustomed to providing minimal amounts of information to project teams about the requirements (and these often are phrased in terms of the solution instead of the business need), and then sending the team off to do the real project work. The business analyst uses her influence, negotiating skills, and credibility to secure the participation of key business SMEs throughout the project. This involves building a strong relationship with the business owner, who is often the project sponsor, as well as other key business leaders who are influential in committing the essential SMEs.

As the requirements team comes together in workshops or other working sessions, they will inevitably pass through the same team development stages as the larger project team. The business analyst must navigate the team through the challenges of each stage of team development. The goal for the business analyst is to optimize the dynamics and expertise of the business SMEs to foster an innovative and creative atmosphere for determining business opportunities and solutions. Remember: business analysts are not note takers—they are creative leaders.

What best practices should you as the business analyst employ as the requirements team leader?

- Meet face-to-face with business representatives, customers, and end users early and often.

- Devote time and energy to guide the requirements ownership team through the stages of team development, changing your leadership style as the team moves in and out of stages.

- When forming the requirements team, utilize the core team concept (small but mighty collocated teams that work collaboratively). Involve key technical SMEs (architect, lead developer, application portfolio manager) in the key working sessions of the requirements ownership team.

- Spend enough time training requirements team members on the requirements practices and tools the team will use so that they will be comfortable with the process before they jump in head first.

- Build a solid, trusting, collaborative relationship among the project team members and the requirements technical and business SMEs.

- Bring in additional SMEs and form subteams and committees when needed to augment the core requirements ownership team.

- Establish a requirements integration team to structure requirements into process groups and to manage interrelationships among requirement groups.

- Encourage frequent meetings among the core requirements and project team members to promote full disclosure and transparency as the inevitable trade-off decisions are made.

It is not enough for the business analyst to develop requirements engineering knowledge and skills. It is also important to understand—and use—the power of teams, which leads to much more creative solutions.

Creativity: A Right-Brain Pursuit

A creative team that comes up with brilliant ideas is one of the most valuable resources any organization can have. If you want to give your creative team the best possible chance for success, give them clear ground rules and then let them run free.

—Bill Stainton, TV executive producer, speaker, author

At this point, you might be questioning our assertion that business analysts should serve as creative leaders. You might be thinking that analysts are just that—analytical, logical, methodical, questioning, reasoned, and rational. Isn’t this left-brain stuff? In fact, the business analyst needs to learn how to optimize both sides of her brain. How is the business analyst to become a creativity catalyst? By using creativity-inducing tools and techniques that make use of structured, proven problem-solving and decision-making methods (left brain) and cleverly augmenting them with investigation, experimentation, and yes, experiencing a little bit of chaos along the way (right brain).

As business analysts rise to the top of their game, they will skillfully learn to balance both the left and right sides of the brains of their SMEs (see below) in addition to their own brains. They will inspire teams to invent, imagine, and experiment. But they also will have a keen understanding of the business opportunity, the customer desires, the market window, and the executive team’s tolerance for ambiguity and research. The seasoned business analyst will instinctively know just the right moment to end experimentation and have the team put a stake in the ground. They will understand the concept of last responsible moment decision-making (i.e., do not shut down experimentation and lock into a design until it would be irresponsible to delay solution construction any longer; a delay would mean that the solution would be suboptimized and the opportunity lost.)

Right Brain vs. Left Brain Preferences

Getting There: From Ad Hoc Group to Working Group to Creative Team

According to Bill Stainton, whose presentations combine “business smarts with show biz sparks” (this is a great mental model for the creative business analyst leader), the only difference between creative and non-creative people is that creative people believe they are creative.[8]Stainton suggests that it is the job of the leader of a creative team to make its members believe that they too are creative. The leader of innovative teams does this by providing:

- Direction. Set down boundaries, rules, and clear targets for the team. Some believe rules and boundaries limit creativity. In fact, clear targets focus us on the task at hand and liberate us to be creative.

- Freedom. Do not tell your team how to achieve the targets. Creative people need the space to “play, explore, and discover.”

- Stimulation. Creative people thrive in an inspirational environment, but their creativity dies in a sterile one.[9]

Commonly Understood but Little-Used Practices

The team leadership practices leadership consultant Don Clark suggests are well known, but they are not implemented often enough. A great team leader is constantly assessing the extent to which his team possesses these critical elements:

- Inspiration: Continually reinforce the importance of the creative process to the organization as well as the value of the opportunity at hand.

- Urgency: Develop and maintain a sense of urgency; this keeps the creative juices flowing and time-boxes decision-making.

- Empowerment: Keep the team informed; challenge them with fresh facts and information. New knowledge just might redirect their effort or rekindle their creativity.

- Togetherness: Teams need formal and informal time together to build constructive relationships and trust each other. One team member remarked, “We did our most creative work on a sailboat.” The team leader serves as the catalyst that brings the team together.

- Recognition: Recognize accomplishments and communicate enthusiastically about successes. Insist on working toward small wins to sustain motivation.

- An overarching goal: Although your team might have a number of goals, one of them must stand out as nonnegotiable.

- Productive participation of all members: If certain members of the team are not truly engaged, the team decisions will not benefit from their perspectives, and the team may miss out on creative ideas. Communication, trust, a sense of belonging, and valuing diversity of thought and approaches are all elements that encourage full team participation. Diversity is a vital ingredient that fosters team synergy. If team members are not all engaged in articulating new ideas and challenging each other, the team has not yet reached its most creative point.

- Shared risk taking: If no one individual fails (we all sink or swim together), then risk taking becomes a lot easier.

- Change compatibility: Being flexible and having the ability to self correct.[10]

Collaboration: The Glue That Binds Creative Teams

Perhaps the most essential element of great innovation teams is collaboration. Jim Tamm, a workplace expert specializing in building collaborative work environments and the co-author of Radical Collaboration, tells us that collaboration does not magically happen. He contends that collaboration is both a mindset and a skill set—both of which can be learned—that can make a big difference to a company’s bottom line. After almost two decades of teaching collaborative skills in highly challenged and hierarchical organizations, Tamm discovered five essential skills for building successful collaborative environments:

- Think win-win. Foster a positive attitude among your team members; recruit and reward people who are fun to work with and aren’t afraid of (and in fact, actually welcome) challenges and hard work.

- Speak the truth. Dishonesty is toxic in the workplace. Always be open and honest, and expect others to do the same.

- Be accountable. Take responsibility for your performance and interpersonal relationships. Focus on innovative solutions—the hallmark of successful teams.

- Be self-aware—and aware of others. Work hard to understand your own behaviors, and work just as hard to diagnose and optimize the behaviors of your team.

- Learn from conflict. Expect and capitalize on conflict—it happens whenever people come together. The secret to success is to use the conflict to learn and grow.[11]

The Innovation Imperative

Every organization—not just business—needs one core competence: innovation.

—Peter Drucker, writer, management consultant, and self-described social ecologist

The United States has enjoyed a preeminent position in the world economy for decades, largely riding the wave of success brought about by the world’s greatest innovators: Alexander Graham Bell, Henry Ford, George Eastman, Harvey Firestone, John D. Rockefeller, George Westinghouse, Andrew Carnegie, and of course, Thomas Edison. However, the 21st century brought with it immense global competitive pressure that is putting the U. S.’s economic domination at risk. Studies indicate that global innovation leadership is shifting away from the U.S., heading east to the emerging markets of China, India, and South Korea. Now is the time for us to revisit tried-and-true innovation skills and practices and once again seize competitive advantage. Business analysts are well positioned to play a vital role in this effort as they work with teams across the enterprise.

According to Jon R. Katzenbach, author of Teams at the Top, and Stacy Palestrant, a team is “a small group with complementary skills committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and working approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.”[12] It may be easy to define what Katzenbach calls real teams, but they are very hard to build and even harder to keep going.

Sustained Inspiration

Katzenbach and Palestrant write that teams can initially sustain their inspiration, motivation, and drive if they are presented with a compelling performance challenge. As BAs begin to work on mission-critical innovation projects, they are undoubtedly presented with a compelling performance challenge. At the outset, teams seem to ride on the wave of their instincts and desire to do good work. Real teams, however, succeed only if their leaders make sure the team members consistently apply what is referred to as the essential discipline. In a situation where performance challenges are changing rapidly, which is almost always the case in today’s Internet-speed business cycles, it behooves team leaders to continually assess team health and instill team discipline.[13](*Is this entire paragraph based on Katzenbach & Palestrant? If so, insert new note.)

A Team Culture of Discipline

As Jim Collins writes in Good to Great, it is important that organizations build a culture of discipline.[14]It is a commonly held misconception that the imposition of standards and discipline discourages creativity. A project team is like a start-up company. To truly innovate, the team needs to value creativity, imagination, and risk-taking. However, to maintain a sense of control over a large team, we often impose structure, insist on planning, and institutionalize coordination systems of meetings and reports.

The Entrepreneurial Death Spiral

As we have discussed, the risk of requiring too much rigor is that the team becomes bureaucratic. Collins calls this the entrepreneurial death spiral. He contends that “bureaucracy is imposed to compensate for incompetence and lack of discipline—a problem that largely goes away if you have the right people in the first place.” The goal is to learn how to use rigor and discipline to enable creativity. Great teams (think emergency responders and surgical teams) almost always have rigid standards; they practice the execution of those standards over and over again until they become second nature; and they work hard to examine each performance and improve the standards based upon experience. So, as Katzenbach tells us, “Team performance is characterized at least as much by discipline and hard work as it is by empowerment, togetherness, and positive group dynamics.”[15]

Quick Team Assessment

Jim Clemmer writes, “Despite all the team talk of the last few years, few groups are real teams. Too often they’re unfocused and uncoordinated in their efforts.”[16]Clemmer developed the following set of questions based on his consulting and team development work. This team assessment and planning framework can be used to help newly formed teams come together and get productive quickly or to help existing teams refocus and renew themselves. Use this simple approach to assess team performance by having your team develop answers and action plans around each question. Perhaps add a question or two about creativity, innovation, and operating at the edge of chaos.

- Why do we exist (our purpose)?

- Where are we going (our vision)?

- How will we work together (our values)?

- Who do we serve (internal or external customers or partners)?

- What is expected of us?

- What are our performance gaps (difference between the expectations and our performance)?

- What are our goals and priorities?

- What’s our improvement plan?

- What skills do we need to develop?

- What support is available?

- How will we track our performance?

- How/when will we review, assess, celebrate, and refocus?[17]

Putting It All Together: What Does This Mean to the Business Analyst?

The lesson for the business analyst is this: work hard with other project leaders to impose a culture of discipline in your project team. Build improvements into the team’s interactions, imaginings, experimentations, problem-solving, and decision-making processes at every feedback point. Become an expert at developing and sustaining high-performing teams. To do this, you need to develop your unique leadership style, one that makes high performers want to be on your team.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

Endnotes

[1]. Thomas A. Stewart, “The Corporate Jungle Spawns a New Species: The Project Manager,” Fortune (July 1995): 179–80.

[1]. Jon R. Katzenbach and Douglas K. Smith, The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 1993), 20-21.

[1]. Poppendieck, LLC, “Reflections on Development,” www.poppendieck.com/development1.htm (accessed May 2011).

[1]. Ibid.

[1]. Katzenbach and Smith, 24-26.

[1]. Bruce W. Tuckman, “Developmental Sequence in Small Groups,” Psychological Bulletin 63, no. 6 (June 1965): 384–399.

[1]. David C. Kolb, Team Leadership (Durango, CO: Lore International Institute, 1999), 9-18.

[1] International Association of Facilitators. Online at: http://www.iaf-world.org/index/Certification/CompetenciesforCertification.aspx (Accessed May 2011).

[1]. Bill Stainton, “How To Lead a Creative Team,” http://ovationconsulting.com/blog/how-to-lead-a-creative-team (accessed August 2010).

[1]. Ibid.

[1]. Don Clark, “Growing a Team,” http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/leader/leadtem.html (accessed August 2010).

[1]. James W. Tamm, “The ‘Red Zone’ Organization,” Innovative Leader 14, no. 5 (January–March 2006), http://www.winstonbrill.com/bril001/html/article_index/articles.html (accessed August 2010).

[1]. Jim Clemmer, “Harnessing the Power of Teams,” http://ezinearticles.com/?Harnessing-the-Power-of-Teams&id=109593 (accessed August 2010).

[1]. Ibid.

[1]. Jon R. Katzenbach and Stacy Palestrant, “Team Leadership: Emerging Challenges,” Innovative Leader 9, no. 8 (August 2000), http://www.winstonbrill.com/bril001/html/article_index/articles/451-500/article482_body.html (accessed May 2010).

[1] Ibid.

[1]. Jim Collins, Good to Great (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2001), 120–143.

[1] Jon R. Katzenbach and Stacy Palestrant, “Team Leadership: Emerging Challenges,” Innovative Leader 9, no. 8 (August 2000), http://www.winstonbrill.com/bril001/html/article_index/articles/451-500/article482_body.html (accessed May 2010).

Look for Next Month’s Article: Igniting Creativity in Complex Distributed Teams

[1]. Jon R. Katzenbach and Douglas K. Smith, The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 1993), 20-21.

[2]. Poppendieck, LLC, “Reflections on Development,” www.poppendieck.com/development1.htm (accessed May 2011).

[3]. Ibid.

[4]. Katzenbach and Smith, 24-26.

[5]. Bruce W. Tuckman, “Developmental Sequence in Small Groups,” Psychological Bulletin 63, no. 6 (June 1965): 384–399.

[6]. David C. Kolb, Team Leadership (Durango, CO: Lore International Institute, 1999), 9-18.

[7] International Association of Facilitators. Online at: http://www.iaf-world.org/index/Certification/CompetenciesforCertification.aspx (Accessed May 2011).

[8]. Bill Stainton, “How To Lead a Creative Team,” http://ovationconsulting.com/blog/how-to-lead-a-creative-team (accessed August 2010).

[9]. Ibid.

[11]. Don Clark, “Growing a Team,” http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/leader/leadtem.html (accessed August 2010).

[11]. James W. Tamm, “The ‘Red Zone’ Organization,” Innovative Leader 14, no. 5 (January–March 2006), http://www.winstonbrill.com/bril001/html/article_index/articles.html (accessed August 2010).

[12]. Jon R. Katzenbach and Stacy Palestrant, “Team Leadership: Emerging Challenges,” Innovative Leader 9, no. 8 (August 2000), http://www.winstonbrill.com/bril001/html/article_index/articles/451-500/article482_body.html (accessed May 2010).

[13] Ibid.

[14]. Jim Collins, Good to Great (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2001), 120–143.

[15] Jon R. Katzenbach and Stacy Palestrant, “Team Leadership: Emerging Challenges,” Innovative Leader 9, no. 8 (August 2000), http://www.winstonbrill.com/bril001/html/article_index/articles/451-500/article482_body.html (accessed May 2010).

[16]. Jim Clemmer, “Harnessing the Power of Teams,” http://ezinearticles.com/?Harnessing-the-Power-of-Teams&id=109593 (accessed August 2010).

[17]. Ibid.

As businesses acknowledge the value of business analysis – the result of the absolute necessity to drive business results through projects – they are struggling to figure out three things:

As businesses acknowledge the value of business analysis – the result of the absolute necessity to drive business results through projects – they are struggling to figure out three things:

With so much riding on successful projects, the business analyst is emerging to fill the gap in creativity, analyze the business and the competitive environment, and provide the expert facilitation needed to achieve

With so much riding on successful projects, the business analyst is emerging to fill the gap in creativity, analyze the business and the competitive environment, and provide the expert facilitation needed to achieve