Solve it with Science

Remember those days in elementary school science class when the teacher would stand up in front of everyone and ask a question that required solving? The question was always designed to get the neurons in our brains firing, and begin brainstorming solutions to the problem. During those brainstorming sessions we’d eventually develop a problem statement or hypothesis, which was synonymously referred to as a hunch amongst the kids in class. Whether we realized it or not, our hunch or problem statement would become the foundation of our problem-solving process; the postulation as to why we felt the subject matter in question was occurring, and the possible causation.

Eventually we’d start going through the motions of testing our hypothesis; identifying our manipulated and controlled variables in hopes that it would provide us with a responding variable that would confirm our hunch. If at the end of our experiments we found that our theory wasn’t supported, then we’d develop a new hypothesis and start the process again.

So with that said, couldn’t a simplistic view of solving problems the way we used to when we were kids be applied to our problems today? The use of this basic method of theorizing and experimenting can become an intricate tool in solving problems that plague or hinder the success of a project.

This article is designed to remind and re-engage you in a thought process that was taught to us at a young age and that can help you tackle the problems impacting your project today. What this article is not designed to be is an exercise in technical jargon or buzzwords, but one focused more on the utilization of simple logic when trying to figure out the root cause of an issue.

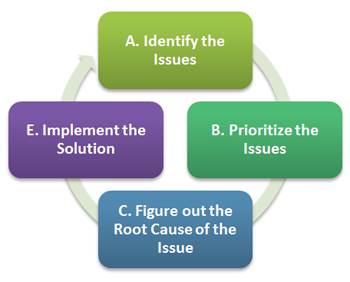

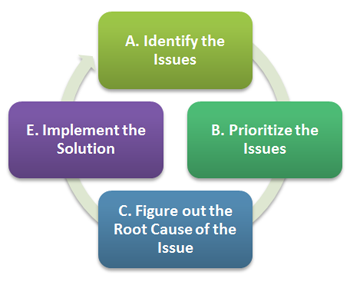

No matter what the issue is, a similar thought process should be running through all our minds when identifying and responding to a problem:

Figure 1

A. Identify the Issues

Begin by understanding what problems have been plaguing the project (e.g., a lack of project charter, poor team member participation, etc.). A suggested approach is to go through the original plan for the project and perform a gap analysis of where things should be versus where they are today. As a member of the team, or as project manager (“PM”), you should have a good idea of what’s been slowing down the project. Consideration should also be given to collaborative discussions with the team that could also bring to surface issues that may not be apparent to all members or the PM but could have a material impact on the success of the project.

Once you’ve gone through and listed potential problems, the next suggested step is to risk rank each issue to determine their importance and resolution priority.

B. Prioritize the Issues

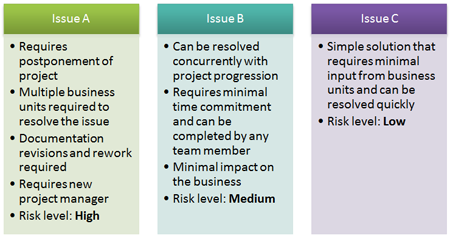

To determine which issues to tackle first, the suggested approach is to risk rank each issue and prioritize each based on complexity and impact. In this context, complexity can be viewed from many perspectives. But to provide simplicity and ease of thought, consider viewing it from a component standpoint (e.g., how many information inputs and outputs are impacted by the problem, how many parties or business units are impacted, etc.). For example, compare the following three issues:

Complexity:

Comparing each issue, it’s easy to identify that issue A is more complex than issue C, involves a greater degree of effort to resolve, and impacts more business units and information outputs than issue C.

Now that we have a basic understanding of complexity, let’s move on to the impact component of the risk ranking exercise.

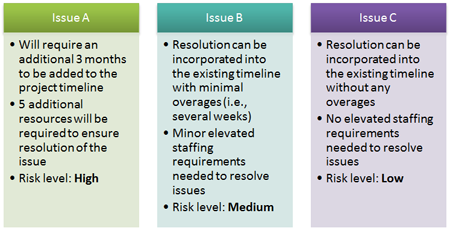

Impact can be interpreted as the level of damage the issue can cause if it goes unresolved. The damage, for all intents and purposes, is most easily understood when quantified in terms of time required for completion and effort expended; this understanding translates nicely with project timelines and helps provide clarity when the project and identified issues are monetized to the project sponsor. Consider the same issues above, but this time with impact as the risk consideration:

Impact:

With an understanding of complexity and impact, the final step is to map each against a risk grid. The grid visualizes where your issues rank and helps to vet which issues should be tackled first, from highest to lowest risk. A typical grid that could be used is as follows:

Figure 2

|

Risk Ranking |

Complexity |

|||

|

Low |

Medium |

High |

||

|

Impact |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

|

Medium |

Low |

Medium |

High |

|

|

High |

Medium |

High |

High |

|

Using the grid above, you should now be able to generate a list of issues that are prioritized based on the level of complexity and the overall impact they can have if left unresolved.

C. Figure out the Root Cause of the Problem

Now that you know which issues require immediate attention, the next step is to postulate the cause of the problem, because understanding why the problem is occurring or has occurred will be the only way to develop insight into developing a solution. For example, if the top-ranked risk for your project is that team members no longer attend project meetings, the first step is to develop a hypothesis as to why this may be occurring. The key of the hypothesis is stating the effect and the proposed cause that requires confirmation through experimentation, whether it is confirmed empirically or simply with reasons jotted down on a bar napkin. If, through your hypothesis and experimentation, you determine that no one is attending the meetings (effect) because food isn’t provided to attendees (cause), you can now move towards resolving the issue (i.e., provide food at meetings). The simplicity of the example may seem a bit ridiculous, but you’ll be surprised as to the simple cause of some of the problems impacting your projects.

D. Implement the Solution

The final step when trying to resolve issues is to implement the solution developed during the root cause analysis process. It’s during this time that you’ll be able to tell whether the hypothesized solution will in fact work (i.e., does providing food at meetings actually result in more people attending?). If during this process and the post-implementation of the solution there exists a gap between what is expected versus what actually results, there may be a need to reinitiate the problem-solving process (i.e., repeat step C.)

If the problem is large or complex enough with multiple variables, the above process can become quite extensive but the baseline principles will still hold the same.

To summarize, thoughtful thinking throughout the problem-solving process is essential to the success of resolving issues in a timely and effective manner. It’s important to be cognizant of your actions and activities throughout a project. Emphasizing a greater effort in planning with a preventative mindset in place aims to ensure that problems won’t arise due to a lack of project charter, multiple project sponsors, etc. If, unfortunately, you are experiencing problems with the project, barring any unusual or extreme circumstances, consider the steps above to help devise a simple and methodical strategy for resolving issues threatening your projects completion.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

Neil Karan, CFE, CISA is an experienced financial process and IT auditor who provides direction and guidance for audit and project programs. His areas of expertise include business process effectiveness and efficiency programs, operational process design and financial/IT integrity audits.