Business Analysis Scenarios; Understanding the Business Interactions

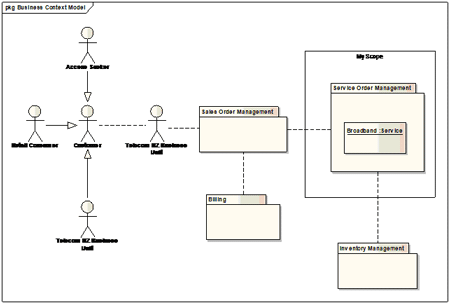

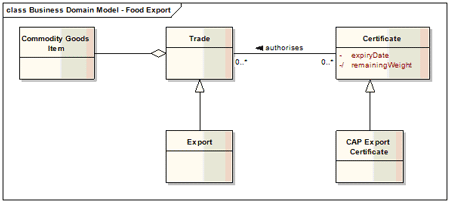

In previous articles we examined the use of a business context model, and which concepts exist and what is true, using a business domain model. And we looked at how business behaves in the business analysis process article.

This article discusses the role of Business Scenarios to express connections between people and business elements and suggests a way to model them. Even to this day, the clarity and beauty of the jewels of truth of a business are frequently obfuscated in an avalanche of inexplicit verbiage (ha ha!) – and the poor old techies have to pick out the gems from the piles of verbal diarrhea disguised as ‘documentation’.

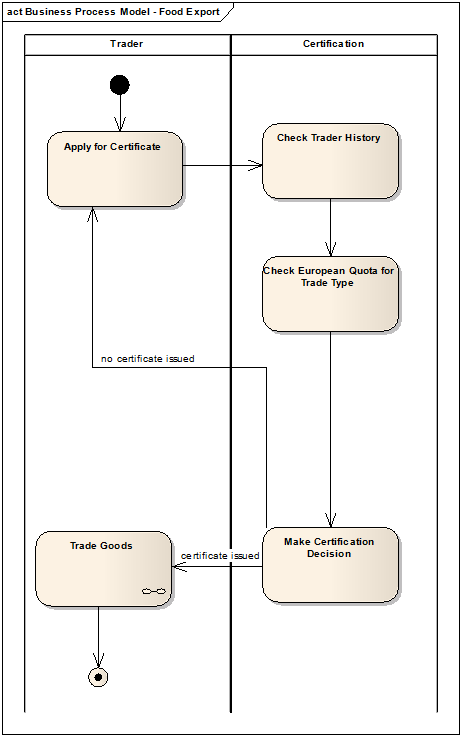

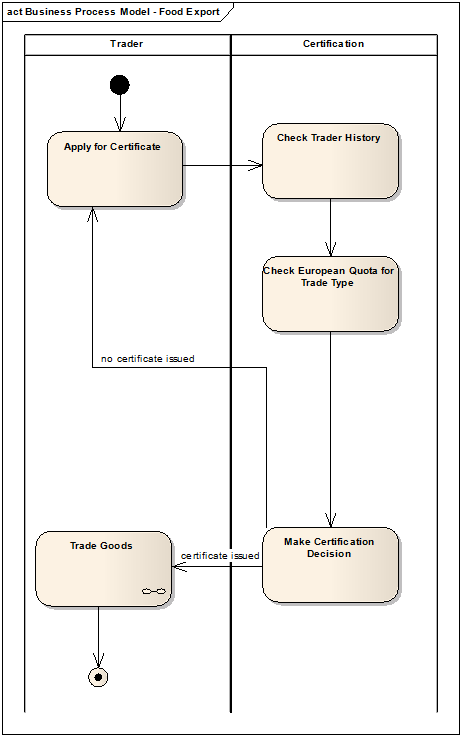

A business scenario can be used to:

- Understand the business interactions.

- Prototype or storyboard a piece of software from a business point of view without presenting screens and buttons which distract from the point of the exercise, thereby keeping the design activity separate.

- Test the completeness of requirements, thereby finding gaps in the logic understood so far. For instance:

- Test for completeness a single path through a business process or use case

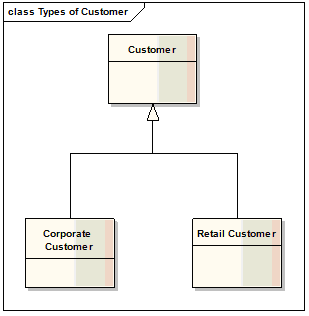

- Find characters in the story (domain classes) that have been missed and their responsibilities

- Understand changes to characters in the scenario (state changes)

- Understand a ‘user story’

- Use as a test case for a new system component

- Take notes as an observer or to further our own understanding; a tool for asking questions.

The aim of a scenario is to understand and communicate a single interaction between the people, systems or anticipated logical components of a business or system. In other words, a business scenario is simply a conversation between people or things/objects in the business.

Scenarios are also a good tool for testing theoretical business processes and domain models by using real-life examples or instances of a situation and the people in it. Although we are specifying behaviour in a business scenario; specifying one single real-life instance renders business scenario modelling a separate tool from modelling business process or use cases.

So how do we start building a business scenario? Using the idea of holding a conversation, imagine that all the things that exist in the business are people or invent people that can talk to other people. For example, I need a way to handle billing once I’ve placed an order. I don’t know what the concepts are yet for billing but I do know that there exists something called Order. Imagining that Order is a person, it will need to have a conversation with some other thing or person. I’m going to call it the Billing Manager (a logical component because I don’t know enough to break that down yet). Now these two ‘actors’ in the business process can have a specific dialogue (say, a single path through a business process or use case if these have been specified already).

Business scenarios can be written as a set of scenario clauses of requests and orders moving around the business using the following grammatical construct: – subject verb noun object

Example Scenario:

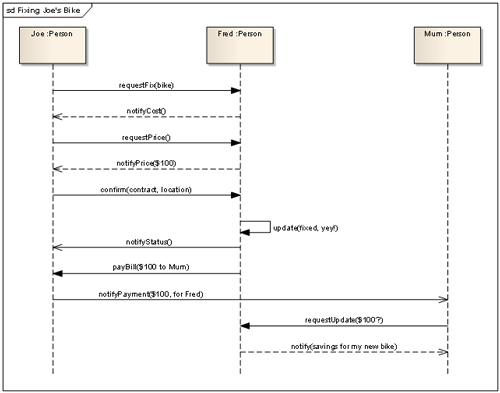

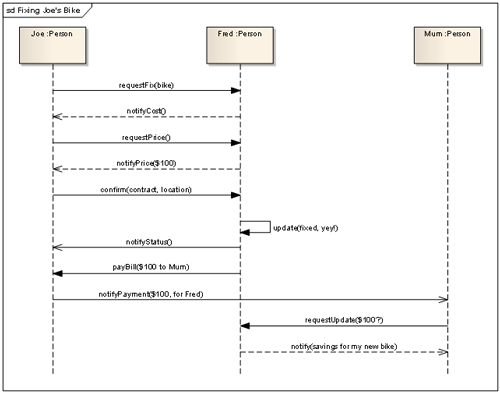

Joe asks “will you fix my bike?” to Fred

Fred replies “yeah, if you pay me” to Joe

Joe asks “how much?” to Fred

Fred replies “$100 mate” to Joe

Joe says “OK” to Fred

Joe gives bike to Fred

Fred fixes bike

Fred says “I’ve fixed your bike. Please give the $100 to Mum” to Joe

Joe says “thanks, I will” to Fred

Joe pays $100 to Mum

Mum asks “what’s the $100 for?” to Fred

Fred replies “savings for a new bike” to Mum

This is a perfectly valid way of expressing a business scenario. However, the old problems crop up. We have written “Joe” nine times instead of once, “Fred” 11 times instead of once and written “Mum” four times instead of once, thereby increasing our workload. We cannot reuse what we have created in this scenario To use or reuse “Joe” say, in other artefacts; we have to type “Joe” or copy “Joe” each time. In addition, the knowledge gained here will be lost in a document and difficult to find later on, as opposed to maintaining business architecture in a good modelling tool allowing us to simply drag Joe into the picture next time he crops up in conversation. The model element “Joe” would not be a modified clone. It would be the one and the only Joe.

One way of introducing stakeholders to modelling business scenarios is to begin writing it as above on a whiteboard, and then convert it into a diagram by erasing the object names on the left and right sides, and by adding the direction (arrows) of ‘conversation’ and the people (object lifelines) involved as follows:

| Joe | Fred | |

| “will you fix my bike?”→ | ||

| ←“yeah, if you pay me” | ||

| “how much?”→ | ||

| ←“$100 mate” |

Messages are represented by an assortment of arrows (as with all modelling techniques, I recommend that the reader researches the notation available) but basically, the messages sent are either calls (an order or request) for a service of another object or returns (answers) to the calls. (Note that services offered by an object are operations on a class.)

Here is the scenario expressed as a UML sequence diagram:

I prefer to use the Unified Modelling Language (UML) because:

- It is broadly accepted as a worldwide standard formal notation,

- It allows me to cover all the types of modelling I need to do with only one notation

- I can use an existing standard notation with my business audience rather than impose one or more non-universally understood notations that colleagues and I have invented.

- I can maximise the reuse of model elements, reduce my workload and eliminate inconsistencies and errors in terminology, and in notation, across all diagrams.

In my experience, business and technical audiences love the precision and speed of describing the business given by a business analyst who can think in an abstract and logical way, and who uses meaningful labels for model elements. The only exception I have come across was a business owner who claimed to be a verbal thinker and who found it difficult to review a diagram later. However, her complaints to the business analysts were about endless repetition and inconsistencies in text and one feedback comment said ” …should not ignore the business scenarios analysis!” and another “I expected to see those stick diagrams …”.

My recommendation is to use UML sparingly and pragmatically, referencing help manuals to avoid breaking the rules as far as possible. I use only four to five symbols in a workshop session – easily digested by a high calibre business audience. My intention in a workshop is not to teach UML to my business. I may not even mention UML, but simply reassure the audience that I am using the current standard notation to the best of my knowledge for describing business. As I record (much more quickly than I could in prose) what is understood and agreed, I ‘speak’ the symbols as I draw them. Later, when I have formalised the model, I talk it through with those who would like another viewing. My other rule is never to send or hand over a model without having gone through the above process with the business audience.

Back to scenarios: a respected solution architect colleague told me that allowing a business analyst to do sequence diagrams is like handing a carving knife to a toddler. I protested but found myself wondering if he was right. Given the general propensity in organisations to jump into solution mode and talk about systems, he may have seen a number of business analysts stepping on the toes of the solution team instead of focussing on business concepts and objects when modelling, albeit not ignoring constraints imposed by existing solution components. I’ll come back to this point.

As with any modelling technique, it is important to judge when it would be appropriate to use, as there would not be time to develop every possible business scenario. To scope this work, think about the core business services that respond to the goals and expected outcomes of important external stakeholders. On the other hand, I know a business analyst who uses this tool by preference as a starting point for his understanding. If you do use them, then I would recommend modelling the successful happy day scenario i.e. what should happen 80% of the time, and a few major and typical exception scenarios for each major domain of the business. Certainly, in the book I’d like to write, they should be created by the business and testers with the help of the business analyst. For the advanced modeller, I recommend researching the principles of distributed control and encapsulation to reduce the impact of future changes by keeping related behaviour and data together.

Back to my point. Let’s not forget, a business analyst’s role is to analyse the business, describe it and its intentions. In this and the articles referred to at the start, we have focused on understanding, specifying and communicating the problem, the scope and the requirements of business change. If we stick to business concepts and business speak, we won’t run the risk of scaring our audiences with models of a technology bent. We need to record the business talk in a sophisticated and useful way, and keep it looking like a real human conversation.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below

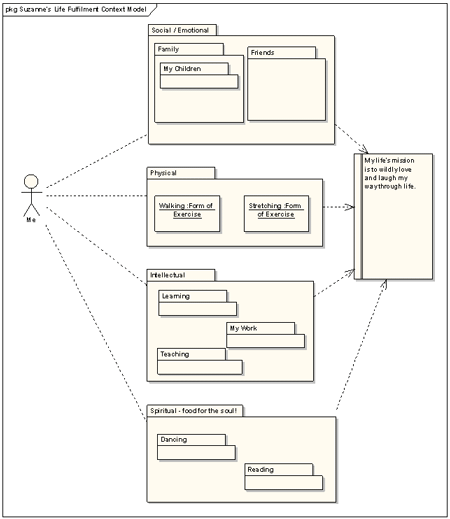

Suzanne Jane Maxted BSc.(Hons), MBCS CITP, is a business architect and analyst with 17 years experience from around the world. She is an accomplished business modeller, workshop facilitator and presenter. Suzanne coaches business analysts and project managers, and is a regular contributor to the Business Analyst Times magazine, with extensive hits and positive feedback from readers. In 2008 and 2009, she was a speaker and panel member at the BA World Symposium in Wellington, NZ. Suzanne fills her spare time teaching and performing dance (performed NZ Dance Festival 2007, Wellington Cuba Street Carnival 2009) and having fun with her two little children. She can be reached at [email protected]

Copyright © Suzanne Jane Maxted, 2010