Best of BATimes: The Quest for Good Requirements

The main responsibility of the analyst is the discovery, analysis, documentation, and communication of requirements. A requirement is simply a feature that a product or service must have in order to be useful to its stakeholders. For example, two requirements for a customer relationship management system might be to allow users to update the payment terms for an account and to add new customers.

In this article, we will look at the different aspects of the requirements management process and the lifecycle of requirements.

Definition of a Requirement

A more precise definition is provided by the IEEE Glossary of Software Engineering Terminology and the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge® (BABOK®). Both define a requirement as a

- condition or capability needed by a user to solve a problem or achieve an objective.

- condition or capability that must be met or possessed by a system or system component to satisfy a contract, standard, specification, or other formally imposed document.

- documented representation of a condition or capability in (1) or (2).

Not all requirements are at the same level. Some might be high level requirements expressed by the business sponsor (e.g., reduce the cost of invoicing customers), others might be very specific requirements that describe a function needed by a particular user (e.g., allow me to click on a customer name and then display that customer’s account history).

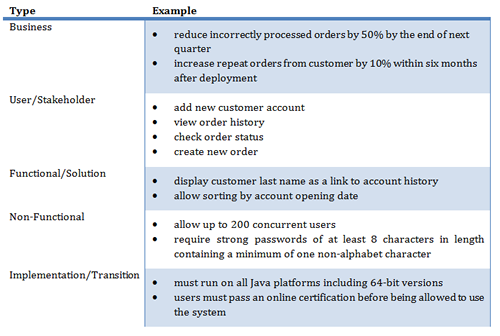

The BABOK® defines the following requirements types: business, user (stakeholder), functional (solution), non-functional (quality of service), constraint, and implementation (transition).

Note that these terms are overloaded and often have different definitions within some organizations. For example, a user requirement is referred to as a business requirement in some organizations and a business requirement is sometimes called a business goal or project objective. Functional requirements are also often called technical requirements, detailed requirements, or system requirements. So, it is important to understand the semantics of the terms being used. If in doubt, ask, but don’t assume. In fact, publish a glossary of terms to clarify the meaning of terms that are used by the project team.

Examples of Different Types of Requirements

To clarify the different kinds of requirements types, let’s take a look at some examples for each type.

Table 1. Requirements Examples

Scope

The scope of a project refers to the agreed upon set of features that the final product will contain. Scope creep is a common occurrence and it describes the propensity of scope to expand as stakeholders add requirements during the project without regard to its impact on budget, schedule, and deliverables. The project manager must work with the stakeholders to get agreement on the scope.

Stakeholders

The stakeholders are the main source of requirements. They have specific needs that the analyst must identify. This is easier said than done: often stakeholders are not quite sure what they need and they often don’t know how to express what they need. It is the analyst’s job to help uncover the requirements of the stakeholders.

A stakeholder is anyone who has an interest in the successful outcome of the project, including project sponsors, users, business executives, managers, developers, clients, customers, vendors, and government or regulatory agencies.

Eliciting requirements is surprisingly hard work. Stakeholders often do not know exactly what they need and eliciting the requirements can be quite challenging. As Fred Brooks has stated so poignantly in his seminal essay “No Silver Bullet: Essence and Accidents of Software Engineering”

“The hardest single part of building a software system is deciding precisely what to build. No other part of the conceptual work is as difficult as establishing the detailed technical requirement, including all the interfaces to people, machines, and to other software systems. No other part of the work so cripples the resulting system if done wrong. No other part is more difficult to rectify later.”

He goes on to say that in a systems development project there are two kinds of complexities that must be managed: accidental and essential (or inherent).

Advertisement

Much of software engineering is focused on reducing accidental complexity, which is the complexity that we add to a project by way of the tools and programming languages that we use. For example, writing code in C is much harder than Java and writing code in Java is much harder than doing a “mashup” with web components.

While it is good to focus on reducing accidental complexity, much of the complexity of a project is rooted in essential (or inherent) complexity. Essential complexity is the difficulty of the problem itself: launching a rocket into orbit is hard no matter what programming language you use. The techniques studied in this book are about managing essential complexity.

Brooks also argues that systems are best developed incrementally. Start with something small that you understand and improve and expand it rather than building the penultimate version at the outset. This approach is the foundation for iterative and agile methods.

Requirements Management

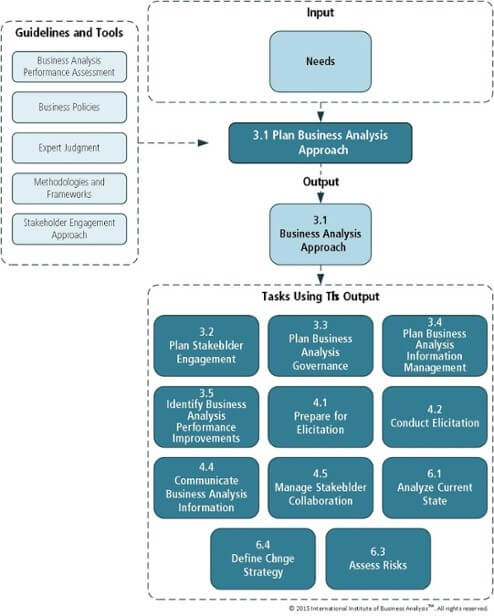

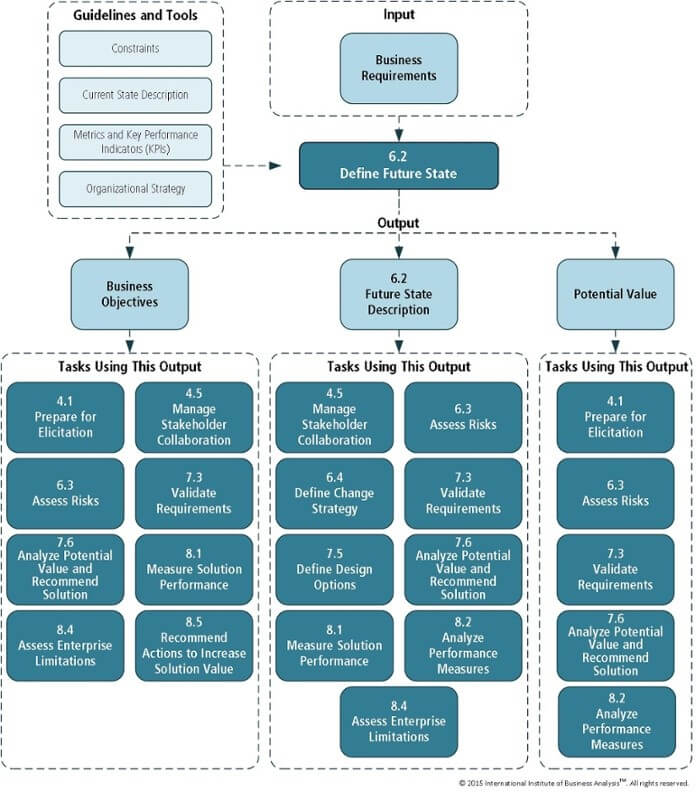

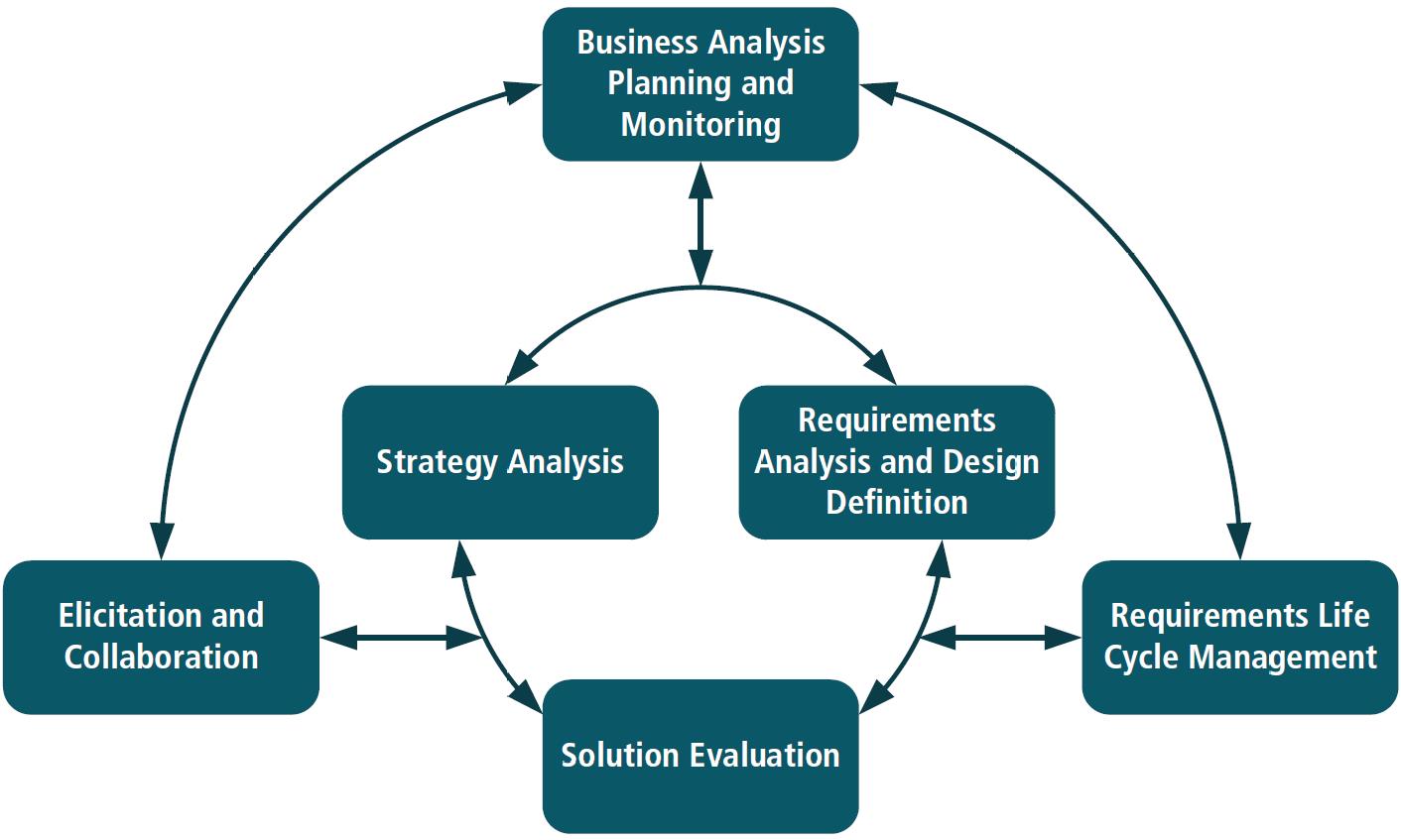

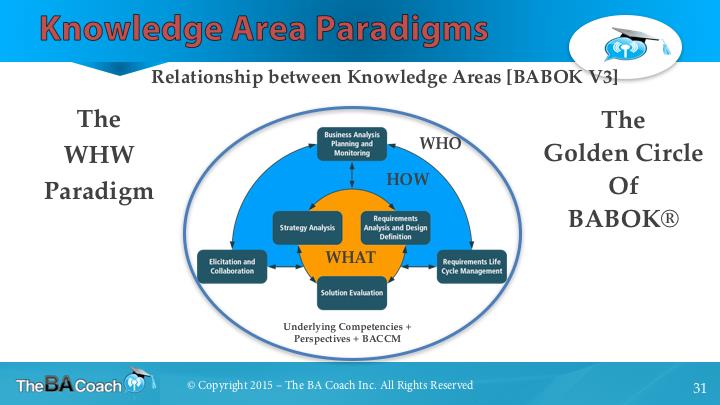

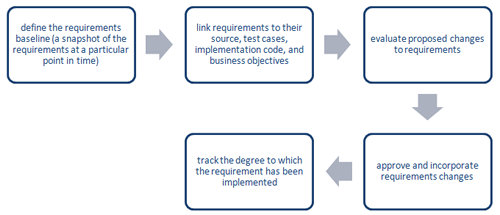

Requirements management is the process of defining and maintaining the requirements that form the agreement between the project team and the stakeholders. A requirements management plan (RMP) is a document that defines the process, procedures, and standards for eliciting, documenting, storing, and updating the requirements. The typical requirement management activities include the following:

Figure 1. Requirements Management Activities

Requirements Management Activities

Requirements management is generally supported by the use of requirements tracking or requirements management tools. There are numerous commercial, free, and open source tools that can be used.

Requirements Process

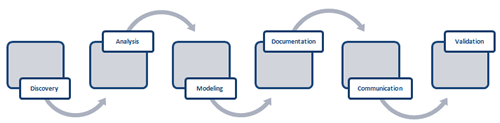

The process of requirements specification can be broken down into discovery (elicitation), analysis, modeling and documentation, communication, and validation (see Figure 2.) As part of the process, the project team must also negotiate the relative importance of each requirement, so that an appropriate prioritization can be established. The requirements that are considered to be implementable within the allocated time and budget are called the project scope or simply scope.

The project team generally implements the requirements in order of priority, starting with the most important ones. The reason is simple: most projects have limited time and budget and commonly not all requirements can be addressed. By the time we run out of time and money the stakeholders would want the most important requirements taken care of. While this sounds simple, establishing and negotiating the priorities of requirements can often be very difficult and politically challenging. Stakeholders don’t want to prioritize for fear of not getting what they want; the project team does not want an unlimited scope as they know that they likely cannot accomplish everything with the allotted resources.

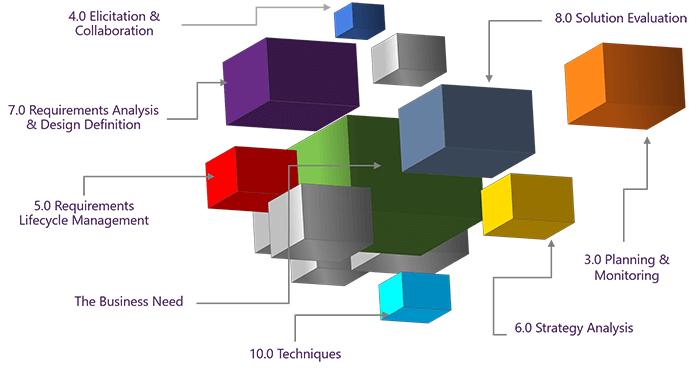

Figure 2. Requirements Management Process

Stakeholder Obligations

For an IT project to be successful, the stakeholders have certain responsibilities:

- they must spend the time with the analyst and educate them about their business and help them understand their objectives

- they need to allocate the time necessary to provide clear requirements and validate the requirements in a timely fashion

- they must precisely describe their requirement; vaguely stated requirements are not implementable and documenting them is a waste of time

- they must provide feedback when needed

- they must provide additional information in a timely fashion

- they must prioritize the requirements

- they must respect the estimates for time and budget provided by the project team and resist the urge to “negotiate”

- they must inform the project team of changes to requirements as soon as they occur

The analyst must continually remind (in subtle ways, of course) the stakeholders of their responsibilities. If the stakeholders don’t live up to them, then that introduces project risks which must be made known to the projects manager and included in the project’s risk catalog.

Requirements Elicitation and Discovery

To discover requirements, the analyst applies a variety of techniques. The steps in requirements elicitation are generally as follows:

- Plan the requirements elicitation process and how the team will document and validate the requirements. This plan is referred to as the Requirements Management Plan (RMP) and is considered a key document for project planning.

- Write a Project Charter or Project Mission Statement containing the business requirements and the overall scope of the project. Often a Context Diagram is provided to clarify the scope of the system development effort. All stakeholders must agree to the vision for the project. Some organizations refer to this document as the Business Requirements Document (BRD). Use brainstorming and interviewing to arrive at the key business requirements.

- Identify the key users and their usage characteristics and select a proxy for each user that can present the requirements for that class of users. These “user representatives” will be consulted throughout the requirements elicitation effort.

- Collaborate with the user representatives to identify use cases and then analyze those use cases to derive the detailed functional requirements for the product.

- Analyze any events to which the system must respond, such as input from hardware devices or messages from other systems.

- Identify any other stakeholders who might provide requirements or constraints.

- Convene requirements workshops in which users work together for a few days to explore user needs and to agree on the requirements. Requirements workshops are a way to reduce the amount of time it takes to find all the requirements by getting everyone together at the same time. Joint Requirements Planning (JRP) and Joint Application Development (JAD) are examples of facilitated requirements workshops.

- Shadow users as they perform job tasks and use the results of the observations to identify needs and to understand business processes. Document these insights in flow charts or UML Activity Diagrams.

- Hold feedback sessions during which users can provide feedback on issues or problems with the current system. The results can be used to formulate requirements on how to enhance the system. Looking at problem reports from the help desk can be particularly insightful.

- Build a prototype that demonstrates the requirements and provides realistic feedback to the users.

- Identify, document, and address any risks that might have a negative impact on the project, i.e., that might cause a delay in delivery, an increase in budget, or a reduction in scope.

- Validate the requirements through walkthroughs and other formal or informal meetings with stakeholder to assure that the right requirements have been discovered.

Requirements Analysis

As soon as requirements have been identified, they must be analyzed to ensure that they are correct, not in conflict with each other, and that they are precisely understood by all stakeholders. During analysis, the requirements must be decomposed into sufficient detail so that the project team can accurately estimate effort for implementation and assure that the requirements are indeed feasible.

Analysis Artifacts

During analysis, the analyst constructs a number of textual, digital and visual artifacts, including:

- context diagrams

- use case model

- conceptual data models and data dictionary

- user interface model

- business process models

- prioritized requirements catalog

- business rule catalog

- prototypes (horizontal discovery as well as vertical feasibility prototypes)

Requirements Documentation

To communicate the requirements to the stakeholders for validation and to provide the development team with a thorough understanding of what must be done, the analyst must write a requirements specification. This is simply called the requirements package as there are no industry standards for the format of that specification. Every organization has adopted a different document template. It is important, however, that an organization has a standard document template. The template must be flexible as no single structure will fit all projects.

The successful analyst knows how to select the right documentation techniques and does not limit himself to just one documentation approach, such as wireframes, use cases, or narrative requirements. He blends the different approaches to specify all requirements clearly, unambiguously, and concisely.

While writing documentation is generally not a value-added activity from the user’s perspective, it is a necessary mechanism to mitigate certain project risks. The amount of necessary documentation is dependent on the specific risks that are present, particularly when projects are implemented by outsourcing partners, distributed teams, or when access to stakeholders is limited or sporadic.

Requirements Validation

Requirements must be validated prior to implementation to assure that they are correctly understood and still valid lest the team wastes precious resources implementing functionality that is not needed. Validation is achieved through several means, including:

- Formal and informal inspection: In this approach, the project team meets and walks through the requirements package, including any visual and executable models.

- Stakeholder reviews: Present the requirements, models, and prototypes to the stakeholders for review and validation. At the conclusion of the review, the stakeholders “sign-off” on the requirements to indicate their approval.

- Acceptance criteria definition: For each user requirement (generally expressed as a use case), define post conditions so that tests can be constructed that verify that the requirements have been met.

Writing Effective Requirements

Documenting requirements is an essential part of the requirements process. Over the years, many approaches to documenting requirements have been developed. Among the more prominent recommendations is IEEE Standard 830, which contains the recommended practices for writing software requirements specifications (SRS).

Requirements that are useful, exhibit several important characteristics:

- complete: the requirement must contain all the information necessary to allow the project team to fulfill the requirement

- accurate: the requirement must be correct; validation is generally done through reviews with stakeholders; an accurate requirement cannot be in conflict with another requirement

- testable: the requirement can be verified through a test

- feasible: the requirement can be implemented; there is no technical or other impediment that make the requirement undoable

- necessary: the requirement must describe a feature that the stakeholders actually need; it must relate to a business objective

- unambiguous: the requirement must be described in a simple and concise manner that guarantees that there are no differing interpretations of what the requirement means

- prioritized: the requirement’s degree of necessity relative to other requirements has been established through stakeholder consultation

Documentation Formats

Requirements are commonly written as simple narrative statements. User requirements are best expressed as more elaborate documents. A common format for documenting user requirements are use cases. In addition, constructing visual models simplifies communication of complex requirements. A visual model, such as a UML diagram, can more precisely describe requirements than a written paragraph. It is also easier to discover mistakes in a diagram than a lengthy narrative. A requirements specification typically includes a combination of narratives, use cases, and visual models.

Requirements Identification

All requirements must be labeled so that it is easy to refer to them through a unique handle rather than its description. The following conventions are often used:

- User Requirements are expressed as use cases and use the prefix UC, e.g., UC1.

- Functional Requirements use the prefixes R or FR, e.g., R92, FR876

- Business Requirements use the prefix O (for objective), e.g., O2

- Business Rules use the prefix BR, e.g., BR12

- Non-Functional (or Quality of Service) Requirements also use the prefix R, although some prefer to use NFR, e.g., R14 or NFR23

Requirements Traceability

Requirements must be traceable. That means for any requirement, one must be able to ascertain its source and its realization, i.e., a reason why the requirement exists and a guarantee that the requirement has actually been implemented. Generally, analysts construct a matrix that traces each requirement to implementation, test cases, and sources. The source of a requirement is generally some stakeholder but might also be a regulation or mandate.

Requirements Approval

Many organizations have a formal process of “sign-off” or approval where the customer or project sponsor formally agrees to the requirements that have been captured. While it is somewhat formal, sign-off must be viewed as a project milestone rather than a formal contract. Requirements very likely will still change after sign-off. After all, the business does not remain static; things change constantly in the business world. Project teams must adopt a requirements change procedure that stakeholders can fall back on when a requirement does indeed change. Naturally, the project manager must explain to the stakeholders that a change to the requirements (either by adding, modifying, or removing a requirement from the specification) likely will have an impact on the project’s schedule, budget, and delivery milestones.

While it is desirable for the project team that requirements are eventually “frozen” it is not realistic. The project team should be prepared to continually manage the requirements scope: scope is not static, it is dynamic and the development lifecycle must accommodate the dynamic nature of requirements. Because of that inherent dynamic, agile methods have become more appealing to many organizations. Agile methods acknowledge that requirements change and therefore they do not force a formal “sign-off” and “freezing” of the requirements. Scope is managed much more flexibly and informally in agile projects.

Conclusion

In this article, we summarized the important aspects of gathering, analyzing, documenting, communicating, and validating requirements. The techniques provided should serve as a foundation for your own best requirements management practices.

Published: 01/25/2011

Dr. Martin Schedlbauer, consultant and instructor for the Corporate Education Group, is an accomplished business analysis subject matter expert, and has been leading and authoring seminars and workshops in business analysis, software engineering, and project management for over twenty years. Beyond that, he coaches his clients in business analysis practices, process modeling, and lean project management. When he is not working with his clients or delivering workshops for CEG, he lectures at Northeastern University in Boston in his capacity as Clinical Professor.

[1] Brooks, F., “No Silver Bullet: Essence and Accidents of Software Engineering”. IEEE Computer, 20 (4), April 1987, pp. 10 – 19.

[2] A mashup is a re-combination of available web components to provide powerful new functionality using simple visual editors and little programming. As examples, see Yahoo pipes and Google mashups.