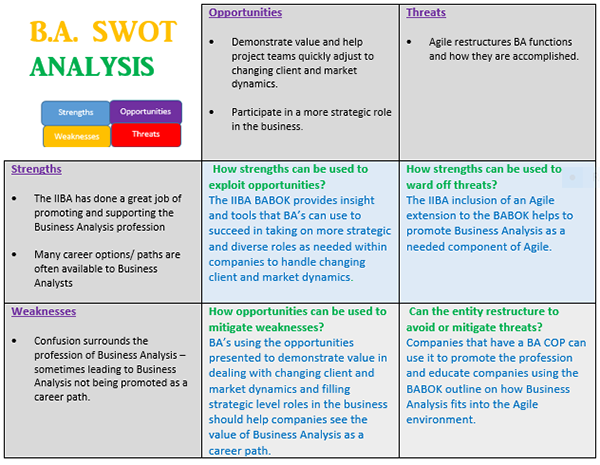

SWOT of Business Analysis

Out of curiosity about the future of a career path that I have been on for more than 2 decades, I have decided to create a SWOT outline of business analysis.

Related Article: 5 Things I Wish I’d Known When I Started as a Business Analyst

SWOT is an acronym for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats—and is a structured planning method that evaluates those four elements:

- Strengths: characteristics of the entity that give it an advantage

- Weaknesses: characteristics that place the entity at a disadvantage

- Opportunities: elements that the entity could exploit to its advantage

- Threats: elements in the environment that could cause trouble for the entity

In creating the SWOT outline, the International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA) BABOK definition of Business Analysis will be used:

According to the BABOK Guide v3, “Business Analysis is the practice of enabling change in an enterprise by defining needs and recommending solutions that deliver value to stakeholders. Business Analysis enables an enterprise to articulate needs and the rationale for a change, and to design and describe solutions that can deliver value. “

Let’s get started!

Strengths:

The IIBA has done a great job of promoting and supporting the business analysis profession. It has given it a voice globally. It also supports the recognition of the profession and works to maintain standards for its practice and certification. It has also provided a model for the formation of regional IIBA communities and Business Analysis Community of Practice entities (i.e. BA CoPs) within companies.

Many career options/ paths are often available to business analysts. The nature of business analysis often involves working with the business to identify business needs, problems, and opportunities while also working with Information Technology teams to define, design and implement solutions. Also, they often have to interact with multiple levels of an organization; strategically, tactically and operationally. Therefore, they gain experience in supporting and contributing to corporate direction, the organization’s enterprise architecture, stakeholder needs and business processes. This wealth of access that business analysts have within companies often place them into a position of having a career path choice in the business and/or Information Technology (IT) realm.

Weaknesses:

Even with the formation of the IIBA and the life of the business analysis profession spanning decades, there is still confusion in the business community around the profession of business analysis, even in regards to the basic question of; “What it is?” I consider this lack of knowledge and confusion to be a weakness because in many companies it leads to business analysis not being promoted as a career path but instead business analysts are being encouraged to take other career paths available in the company as a form of promotion. As stated above as a strength, BAs often have many career path options in the realm of business and/or IT, but for those who want to make business analysis a long time career, promotion can be difficult. I will say that things seem to be improving on this front. I think that knowledge is being gained by the uprise of BA CoP (Business Analysis Community of Practice) entities. They give focus to the BA profession within companies and often with this focus comes recognition of the profession as a career path and its value provided to the company.

Opportunities:

Today, more than ever project teams have to deal with customers that are more than likely extremely knowledgeable about technology and their business processes and how they interact. They are also more demanding, wanting more authority and freedom in the decision-making process. This has led to shifts in business models, support provision needs, requirement elicitation methods and solution recommendations. Business analysts have the opportunity to drive accelerated change management in dynamic markets, filling a more strategic role in regards to enterprise architecture, demonstrating value and helping project teams quickly adjust to changing client and market dynamics.

Project organizations also have to ensure project deliverables are validated against both project requirements and the strategic requirements of the business at the business unit and/or corporate levels. This is to ensure a link exists between strategy and execution. The business analyst can be of great value in working with customers and project teams to keep them aligned in regards to business value to be delivered and how.

Threats:

Because threats are elements in the environment that “could” cause trouble for the entity, in this case, business analysis, I am listing agile as a threat. This is “not” in the sense of it eliminating the business analyst functions from the team. The IIBA has added an agile extension to the BABOK guide which provides an outline of how practices, tools, and techniques can be used by business analysts working in agile environments, and I will concur that there is definitely a need for business analysis functions on agile teams. I will say that agile environments often institute changes to the BA functions and/or how they are accomplished. In some cases, the BA functions may be distributed among other members/roles of the agile team. In some cases, the BA could be asked to fill the role of a product owner or coach. Even though the product owner and coach roles may utilize some of the BA core competencies defined in the BABOK, often these roles require more focus on vision/roadmap definition, return-on-investment (ROI), pricing/licensing for the product, which gravitates more toward the use of management competencies rather than BA competencies.

Diagram 1: