The close of one year tends to encourage us to reflect on what has occurred in business analysis and project management during the past year and think about future trends. To summarize the trends we saw in 2013, the need for project managers and business analysts to be trusted advisors and to influence stakeholders, whether on an Agile or more traditional project, has not disappeared. The same can be said for the demands to balance distributed teams’ needs for efficient and effective communication tools with organizations’ needs for consistency and security.

The close of one year tends to encourage us to reflect on what has occurred in business analysis and project management during the past year and think about future trends. To summarize the trends we saw in 2013, the need for project managers and business analysts to be trusted advisors and to influence stakeholders, whether on an Agile or more traditional project, has not disappeared. The same can be said for the demands to balance distributed teams’ needs for efficient and effective communication tools with organizations’ needs for consistency and security.

Below are the seven new trends we see in the Project Management and Business Analysis fields for 2014.

1. Continued frothing-at-the-mouth enthusiasm for anything “Agile.”

The “Agile” bandwagon hardly seems to be abating. Whether organizations have really adopted agile, or they have stuck their toe into the shallow end of the “Scrum-but” pool, appetites for big, waterfall-type projects have diminished all around. This concept is further reinforced in the PMBOK® Guide – 5th Edition, released a year ago, which identifies phase-to-phase relationship and project life cycle options that account for waterfall, agile, and everything in between. So even for the PMs who haven’t had exposure to a real agile environment, there is more comfort with the idea that many of the tools and techniques that have served them well in the past can be applied on all types of projects.

PMs will increasingly find it an easy sell to break projects into subprojects or smaller projects, whatever the project life cycle and approach. They know too well the cost of trying to define and control many large projects, and they know their stakeholders would rather see smaller deliverables sooner. It’s not agile, per se, but more, smaller projects will resonate strongly with stakeholders as they define what project success really means to them.

The BA world is equally rabid about Agile, seeing the release in 2013 of the Agile Extension to the BABOK® Guide, ver. 2. Version 3.0 of the BABOK due out in 2014 will have an Agile Perspective, and we won’t be surprised if IIBA produces an “Agile Practitioner” sub-certification akin to the PMI-ACP certification from PMI.

2. Use cases will enjoy a resurgence, particularly on Agile projects.

Five years ago we wrote that we expected “Slightly less reliance on use cases and more movement towards user stories.” While many traditional projects have favored the use case technique these past five years, it is only recently that we have noticed an upsurge in the interest in and questions about use cases on Agile projects. And no wonder use cases are gaining traction. User stories, the most common format for writing Agile requirements, are usually created at a high-level of detail. In order for the delivery team to estimate the story during sprint planning and then build the story, it often has to be elaborated in more detail. This elaboration, called grooming the product backlog, provides enough detail about the story so the team can move forward. This is not an attempt to elicit all the requirements up front, but rather to minimize delays caused by poorly defined requirements.

Many Agile teams are beginning to realize that an effective tool for this grooming is the use case, which provides critical information, such as when the user story begins, when “done is done,” and what criteria have to be met to be accepted by the product owner. They are also seeing the importance of the use case narrative in describing decisions and paths that ultimately lead to the navigation, edits, and messages required for software user interfaces. Sure, teams can obtain this information by impromptu conversations with the product owner, but many Agile teams are starting to realize that the use case structure is ideal for getting the user story done more quickly and completely.

3. Business Analysis Focus on Design.

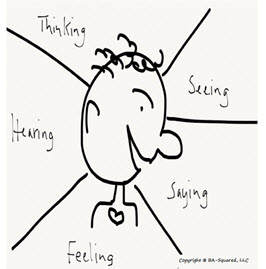

A trend that will continue into 2014 is the notion that business analysis work involves design. Much of the BA’s work includes fashioning solutions, so it is natural to think of this as design work. To some extent the discussion is semantic, in that business analysis has long included design work but using different terms, like “to-be requirements” and “logical design.”

In developing the 3rd edition of the BABOK® Guide, due to be released in 2014, The IIBA® has given “Design” an equal place at the business analysis table. It describes design as “a usable representation of a solution.” (See the article on the IIBA web site.) The technical community may take issue with business analysts doing “design” work, but one thing is clear: the BA community is laying claim to part of the design space and we’re not looking back. Look for an article from us on this topic soon.

4. Increased use of the “cloud” and the need for business analysis in choosing cloud solutions.

Cloud computing will continue to have an allure of the promise to reduce investment in infrastructure and operations. However, it’s been a tense year for those monitoring data security and privacy. Organizations may be increasingly “angsty” about organizational and project information being stored “out there,” but the reality of needing to make information easily available to distributed team members is going to continue to trump those concerns for the coming year as project managers and teams increase use of the cloud for storing and sharing project data.

However, we believe that because of security concerns, organizations’ willingness to analyze their security requirements and to align those requirements to the potential cloud solution’s security features will grow, translating into the need for more analysis of overall requirements prior to investing in new cloud solutions. The growth of cloud technology has created a plethora of options for organizations, so in order to maximize the investment and achieve the greatest value, organizations will use business analysis to evaluate prospective cloud solutions.

5. Less email, more connecting.

The lack of employee engagement is a hot topic these days, and the costs are as significant for the projects in those organizations as they are for the organizations at large. Furthermore, many, if not most, projects use geographically distributed team members, making the obstacles to engagement considerable. We expect that project managers and business analysts are going to spend more planned time in the coming year making an effort to connect with stakeholders, including team members. Fortunately, the number of synchronous communication tools (audio and video) continues to grow, which will increasingly render email a less desirable medium. For those without access to new tools, this may be the year that picking up the phone finds new favor among team members. Overall, those who can let go of the perceived need to document every conversation will reawaken to the intrinsic benefits of communicating with higher-context media other than email which uses only the asynchronous exchange of written words.

6. Business analysis will focus on communicating first and documenting second.

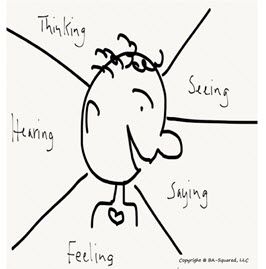

More organizations are realizing that the business analyst brings more value to the organization when they have exceptional skills to listen, observe, question, and probe for the real needs rather than simply producing documentation. As we noted last year, these skills must also include the ability to influence stakeholders in order to get the participation needed for understanding and acceptance of the recommended solution. Further, they must be able to communicate the results of the analysis back to the stakeholders in a way that promotes understanding and gains acceptances and buy-in. We predict that more organizations will jump on the need for “just enough” documentation, realizing that great communication targeted to the group or individual will go much farther than a 500-page requirements document.

7. Project managers will focus on requirements management.

In 2009 we predicted: “There will be a greater emphasis on requirements in Project Management.” This focus has mushroomed during these past five years, in part because PMI has shown a greater interest in requirements activities. The continued expansion of the Collect Requirements section in the PMBOK Guide®– 5th edition, as well as the creation of the PMI Requirements Community of Practice with its numerous webinars and articles on requirements management, has encouraged project managers to become immersed in requirements activities. We anticipate that we will see a new Requirements Management certification from PMI. After all, since PMI has completed a role delineation study, can a related exam be far behind?

Don`t forget to leave your comments below.

About the Authors

Andrea Brockmeier is the Director of Training Services at Watermark Learning. She has over 20 years of experience in project management practice and training. She writes and teaches courses in project management, including PMP® certification, as well as influencing skills. She is actively involved with the PMI® chapter in Minnesota where she has been a member of the certification team for many years. She has a master’s degree in cultural anthropology and is particularly interested in the dynamics of global, virtual teams.

Vicki James is the Director of Business Analysis for Watermark Learning. She is responsible for developing and maintaining Watermark Learning’s Business Analysis Training programs and serving as an instructor for both live in-person and virtual online classes. Vicki has more than 15 years’ experience in the public and private sectors as a project manager, business analyst, author, and independent industry consultant and trainer.

Elizabeth Larson, PMP, CBAP, CSM, PMI-PBA is Co-Principal and CEO of Watermark Learning and has over 30 years of experience in project management and business analysis. Elizabeth’s speaking history includes repeat presentations for national and international conferences on five continents.

Elizabeth has co-authored five books on business analysis and certification preparation. She has also co-authored chapters published in four separate books. Elizabeth was a lead author on several standards including the PMBOK® Guide, BABOK® Guide, and PMI’s Business Analysis for Practitioners – A Practice Guide.

Richard Larson, PMP, CBAP, PMI-PBA, President and Founder of Watermark Learning, is a successful entrepreneur with over 30 years of experience in business analysis, project management, training, and consulting. He has presented workshops and seminars on business analysis and project management topics to over 10,000 participants on five different continents.

Rich loves to combine industry best practices with a practical approach and has contributed to those practices through numerous speaking sessions around the world. He has also worked on the BA Body of Knowledge versions 1.6-3.0, the PMI BA Practice Guide, and the PM Body of Knowledge, 4th edition. He and his wife Elizabeth Larson have co-authored five books on business analysis and certification preparation.

I just returned home for BA World Dallas and had some great conversations, including some during my presentations. During my Business Analysis is Dead, Long Live Business Analysis talk, which is based on my blog of the same name, I was discussing how I see the Business Analyst space changing. The old way of doing business analysis is dead, the new way is alive and well, just different. I asked the attendees how they see their role and a response I received was “We are the bridge between the business and IT.” With a booming voice, helped out by the microphone I had, I yelled “WRONG!” To the responder’s defense, I understood what he was saying…I just used it as an entry point to my make my case. And now, here is my case!

I just returned home for BA World Dallas and had some great conversations, including some during my presentations. During my Business Analysis is Dead, Long Live Business Analysis talk, which is based on my blog of the same name, I was discussing how I see the Business Analyst space changing. The old way of doing business analysis is dead, the new way is alive and well, just different. I asked the attendees how they see their role and a response I received was “We are the bridge between the business and IT.” With a booming voice, helped out by the microphone I had, I yelled “WRONG!” To the responder’s defense, I understood what he was saying…I just used it as an entry point to my make my case. And now, here is my case!

It is customary that at the start of a new year people reflect upon the past and look into the future. I believe you will agree some people are better at both activities than others. In fact, recently

It is customary that at the start of a new year people reflect upon the past and look into the future. I believe you will agree some people are better at both activities than others. In fact, recently

The close of one year tends to encourage us to reflect on what has occurred in business analysis and project management during the past year and think about future trends. To summarize the trends we saw in 2013, the need for project managers and business analysts to be trusted advisors and to influence stakeholders, whether on an Agile or more traditional project, has not disappeared. The same can be said for the demands to balance distributed teams’ needs for efficient and effective communication tools with organizations’ needs for consistency and security.

The close of one year tends to encourage us to reflect on what has occurred in business analysis and project management during the past year and think about future trends. To summarize the trends we saw in 2013, the need for project managers and business analysts to be trusted advisors and to influence stakeholders, whether on an Agile or more traditional project, has not disappeared. The same can be said for the demands to balance distributed teams’ needs for efficient and effective communication tools with organizations’ needs for consistency and security.