Use This Simple Technique to Quickly Understand an Organization

As a Business Analyst, your work is generally concerned with developing an understanding of an organization, and then communicating that understanding in ways that are efficient and actionable. Use this simple technique, outlined below, to quickly understand the aspects of an organization that are typically of interest to a BA.

MODEL OF AN ORGANIZATION

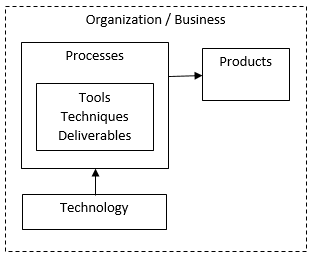

The technique assumes the following model of an organization:

- The organization is engaged in a business

- The organization offers products

- Product development, production, sales, delivery, maintenance, etc. are accomplished through processes

- Processes may include tools, techniques, and deliverables

- Processes may be supported by technology

The figure below that illustrates this model:

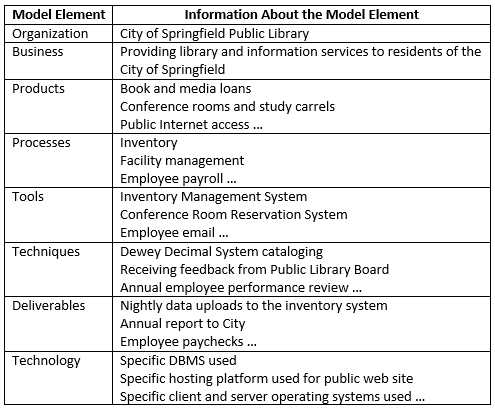

Using the example of a city public library, let’s examine the model in more detail.

ORGANIZATION PERSPECTIVE

The model is general and applies to organizations at all levels. For example, it can apply equally to any of the following:

- A city public library

- A branch of the library

- The library’s payroll department

- The library’s IT department

- The IT department’s database team

Each of these organizations is engaged in a different business. For instance:

- The city public library is in the business of providing library and information services to residents of the city.

- The branch library is in the business of providing a subset of these services to a community within the city.

- The payroll department is in the business of issuing paycheques to library employees.

- The IT department is in the business of building, operating, and maintaining technology for the library. This technology supports processes (like inventory), tools (like employee email), techniques (like Dewey Decimal System cataloging), and deliverables (like employee paycheques).

- The database team is in the business of building, operating, and maintaining databases for the library. For example, it might currently be working on an upgrade to the library’s DBMS.

PRODUCT PERSPECTIVE

One organization’s product can be another organization’s process. Or tool. Or technique, deliverable, or technology.

For instance, the library might purchase new bar code scanners for its inventory management system. From the library’s perspective, the scanners are tools. But from the scanner company’s perspective, the scanners are products.

The scanner company likely has processes for development, production, sales, delivery, and maintenance of bar code devices. For instance, one of its tools might be an automated order entry system.

Let’s say that the scanner company has engaged a consultant to help improve its order entry process. From the scanner company’s perspective, the order entry process is, unsurprisingly, a process. From the consultant’s perspective, the order entry process is a product. And so on.

THE TECHNIQUE

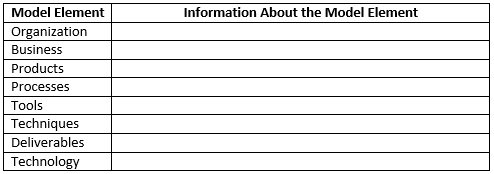

The technique is this – Make a table using the following template, which is based on the organization model. Fill it in with information about the organization. Discover this information using whatever techniques are at your disposal (observing operations within the organization, conducting interviews with employees of the organization, studying documentation, etc.). This may or may not be easy to do, but the “doing” is the most important part; it is where you will organize and clarify your thinking about the organization. (However, the resulting artifact may itself be useful, as described later on.)

Following is a partially completed table based on the public library example:

SOME USES OF THE TABLE

Scenarios in which this technique could be useful to you, as a BA, include:

- You are starting a new job, either with your current employer or with a new employer: Use this technique to assess what you need to know in your new position.

- You are assigned as a consultant to a new client: Use this technique to develop a high-level summary of the client’s “as is” organization.

- You have just hired on with an IT startup: Use this technique to identify what processes, tools, and technologies are currently in place, and which ones need to be defined.

- You are job hunting: Use this technique to define the gap between an advertised position and your own competencies; this is a variation of assessing training needs.

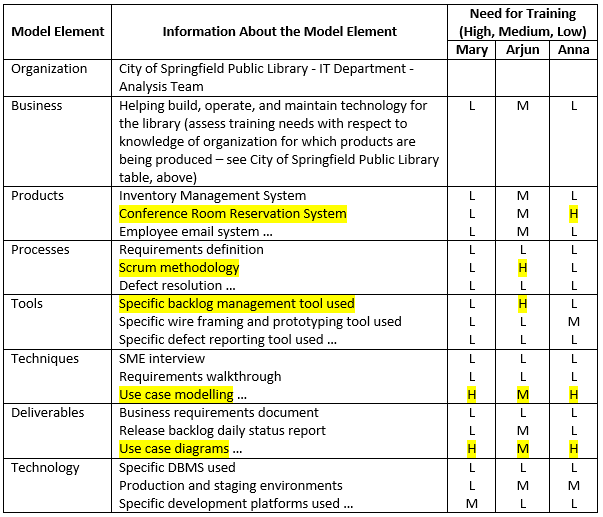

- You are asked to assess the training needs of your team. Use this technique to define the gap between team member competencies with respect to your team’s products, processes, tools, etc. Simply expand the table to include columns for each team member. Enter an assessment of each team member’s competencies and clearly assess where the training needs are.

An example of a training needs assessment, using our library example, could like like this:

From the training assessment table, we can surmise the following:

- Arjun has the greatest training needs. It looks like he may be new to library work. It also looks like he is new to Scrum.

- Anna has need of training in the Conference Room Reservation System (maybe she has previously specialized in the Inventory Management System).

- All three team members are in need of training in use case modelling.

THAT’S IT!

The model and technique are pretty straightforward. I’ve found it useful in various settings but also have gotten into seemingly circular arguments about it. For example: “Why isn’t there an arrow from Technology to Products? Technology supports Products, right?”

If you find that the additional arrow helps, by all means use it. In my thinking, though, each Product is ultimately a Deliverable of some Process. Since Deliverables are supported by the Technology, no arrow is needed.

In any case, I’d like to hear your comments about (and criticisms of) the model and the technique! I hope you find it useful.

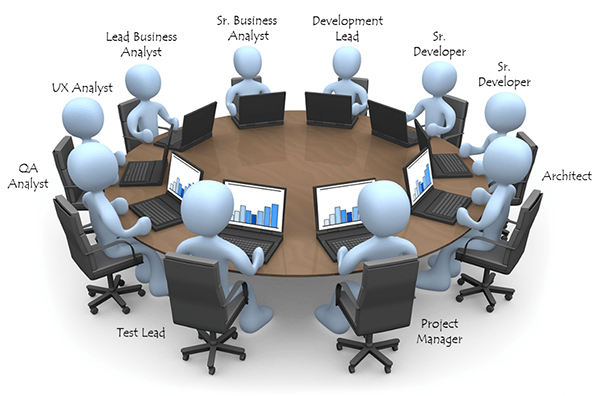

Figure 1: Team built based on roles or titles

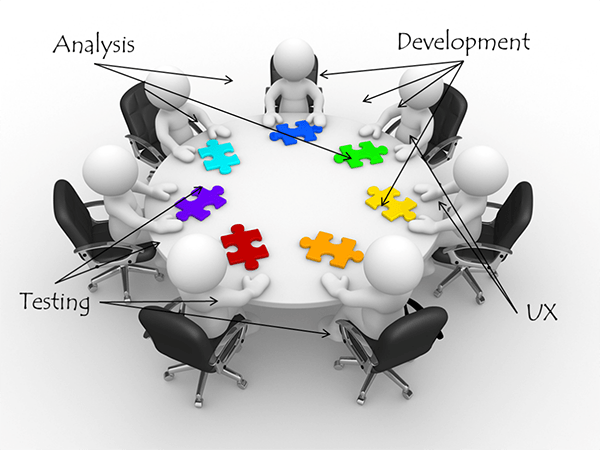

Figure 1: Team built based on roles or titles Figure 2: Team built based on capabilities

Figure 2: Team built based on capabilities

Why are some business analysts better than others? Is it only experience that sets the best apart from the rest or there are some other qualities that separate the “men from the boys”? How do the most successful analysts implement the necessary changes in an organization and make it a habit to recommend solutions that deliver incremental value to all stakeholders of the business?

Why are some business analysts better than others? Is it only experience that sets the best apart from the rest or there are some other qualities that separate the “men from the boys”? How do the most successful analysts implement the necessary changes in an organization and make it a habit to recommend solutions that deliver incremental value to all stakeholders of the business?