When is a so-called requirement really required? And is it the “right” requirement? The answers depend on many facets: stakeholders, value, planning horizon, and so on. This article explores using options as a means to identify high-value requirements, at the last responsible moment.

Our previous article in this series, “Turning Competing Stakeholders into Collaborating Product Partners,” describes stakeholders as product partners –representatives from the customer, business and technology groups who collaboratively discover and deliver high-value product solutions.

My Requirement May Be Your Option

Product requirements are needs that must be satisfied to achieve a goal, solve a problem, or take advantage of an opportunity. The word “requirement” literally means something that is absolutely, positively, without question, necessary. Product requirements must be defined in sufficient detail for planning and development. But before going to that effort and expense, are you sure they are not only must-haves but also the right and relevant requirements?

To arrive at this level of certainty, the product partners ideally start by exploring the product’s options. What do we mean by an option? An option represents a potential characteristic, facet, or quality of the product. The partners use expansive thinking to surface a range of options that could fulfill the vision. Then they collaboratively analyze the options and collectively select options, based on value.

During discovery work, the partners may find that some members see a specific option as a “requirement” for the next delivery cycle, whereas others consider it a “wish list” item for a future release. Such was the case in a recent release planning workshop. The team wrestled with a particular option, questioning if it could deliver enough value to justify the cost to develop it. The product champion explained why the option was a requirement—without it the organization was at risk for regulatory noncompliance. Once the others understood this, they all agreed it would be included in the release.

In a different planning workshop, the systems architect raised the option of using biometric technology to reduce security threats. After carefully considering a variety of factors, including the cost and organizational readiness, the team chose to defer the option.

Count to Seven

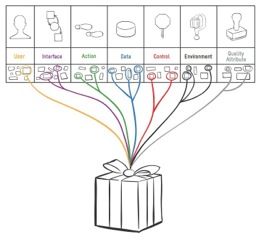

Both agile and non-agile teams often unconsciously limit analyzing the options. Many teams zero in on stories, learning about the users and their actions. Other teams dig into processes or data, or sometimes both of them. But every product has multiple dimensions, seven in fact. Discovering options for each of the 7 Product Dimensions yields a comprehensive, realistic view of the product.

| Product Dimension |

Description |

| User |

Users interact with the product |

| Interface |

The product connects users, systems, and devices |

| Action |

The product provides capabilities to users |

| Data |

The product includes a repository of data and useful information |

| Control |

The product enforces constraints |

| Environment |

The product conforms to physical properties and technical platforms |

| Quality Attribute |

The product has certain properties that qualify its operation and development |

Table 1: The 7 Product Dimensions Yield a Comprehensive Understanding of the Product

The previous article in this series described the Structured Conversation, where the stakeholders, acting as product partners, explore product options across the 7 Product Dimensions, evaluate the possibilities, and make tough choices based on value. Remember, every product option cannot be delivered right now.

Exploring across these 7 Product Dimensions prevents difficult downstream problems. A recent client was struggling with just such a blockage. Running their product on multiple platforms was causing delays that put them behind in their market. As they explored the Environment dimension, they considered browsers and database management systems possibilities. Their analysis factored in the most valuable options from the other six dimensions, including the location of the users, the actions that would be supported and the necessary data. They then selected a cohesive set of options across the 7 Product Dimensions to craft a candidate solution. They were able to make what had once seemed a difficult decision in a matter of minutes. By exploring across the 7 Product Dimensions, their painful problem was resolved with a clear, holistic set of requirements.

Figure 1. A product encapsulates a cohesive set of high value options

Image Source: Discover to Deliver: Agile Product Planning and Analysis, Gottesdiener and Gorman, 2012

Look Far and Near

The partners need to realistically determine when an option will deliver its greatest value.

Our previous article in this series outlined three planning views. The timeframes may vary from team to team, but general speaking they are as follows:

- The Big-View is the long-term view or product roadmap (generally one to two or more years). The partners envision generalized, high-level options for the product. Options for the big-view could be considered “boulder” size, or in user story terms, as epics.

- The Pre-View focuses on the next product release (say one or two months). To continue the analogy, these options are “rock” size, or user-story size.

- The Now-View concentrates on the next product increment (from a day up to a month). The selected options are fine-grained, “pebble size” and defined in sufficient detail for development. They are no longer options but requirements, ready for immediate development.

An aside: We have used the “boulder, rock, pebble” analogy for many years to distinguish granularity in each view, for each of the 7 Product Dimensions.

An agile team keeps the product options “open.” In each view they wait until the last responsible moment to evaluate the options’ value and allocate high-value ones to the next planning horizon. They are prepared to adjust their choices for a variety of conditions, including changing market conditions, emerging technologies, and so on.

From Options to Requirements

Discovering product options enables the product partners to collaboratively and creatively explore a range of possibilities. This expansive thinking opens up product innovation, experimentation, and mutual learning.

By holistically exploring options for the 7 Product Dimensions the partners grasp the entirety of the potential range and can choose the options that deliver the highest value. Using the appropriate planning view (Big, Pre, Now), they narrow the scope. When an option is allocated for immediate delivery it is consider a requirement.

As a recap, we characterize a “right requirement” as one that is:

- Just in time, just enough. It is essential for achieving the business objectives, in this time period.

- Realistic. It is capable of being delivered with the available resources.

- Clearly and unambiguously defined. Acceptance criteria exist that all partners understand and will use to verify and validate the product.

- Valuable. It is indispensible for achieving the anticipated outcomes for the next delivery cycle.

In this series’ next article we focus on value—how the product partners define and use value to select options needed to deliver high-value products.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

About the Authors:

Mary Gorman, a leader in business analysis and requirements, is Vice President of Quality & Delivery at EBG Consulting. Mary coaches product teams and facilitates discovery workshops, and she trains stakeholders in collaborative practices. She speaks and writes on Agile, business analysis, and project management. A Certified Business Analysis Professional™ and Certified Scrum Master, Mary helped develop the IIBA® Business Analysis Body of Knowledge® and certification exam, and the PMI® business analysis role delineation. Mary is co-author of Discover to Deliver: Agile Product Planning and Analysis.

Mary Gorman, a leader in business analysis and requirements, is Vice President of Quality & Delivery at EBG Consulting. Mary coaches product teams and facilitates discovery workshops, and she trains stakeholders in collaborative practices. She speaks and writes on Agile, business analysis, and project management. A Certified Business Analysis Professional™ and Certified Scrum Master, Mary helped develop the IIBA® Business Analysis Body of Knowledge® and certification exam, and the PMI® business analysis role delineation. Mary is co-author of Discover to Deliver: Agile Product Planning and Analysis.

Ellen Gottesdiener, Founder and Principal of EBG Consulting, is a leader in the collaborative convergence of requirements + product management + project management. Ellen coaches individuals and teams and facilitates discovery and planning workshops. A Certified Professional Facilitator and a Certified Scrum Master, she writes widely and keynotes and presents worldwide. In addition to co-authoring Discover to Deliver: Agile Product Planning and Analysis, Ellen is author of Requirements by Collaboration and The Software Requirements Memory Jogger.

Ellen Gottesdiener, Founder and Principal of EBG Consulting, is a leader in the collaborative convergence of requirements + product management + project management. Ellen coaches individuals and teams and facilitates discovery and planning workshops. A Certified Professional Facilitator and a Certified Scrum Master, she writes widely and keynotes and presents worldwide. In addition to co-authoring Discover to Deliver: Agile Product Planning and Analysis, Ellen is author of Requirements by Collaboration and The Software Requirements Memory Jogger.

Ellen Gottesdiener

Ellen Gottesdiener

Strategic planning is an exercise in gathering and documenting information about the past, present and future of your business. Strategic planning helps determine where you want to go over the next few years, how you are going to get there and how to recognize when you’ve arrived.

Strategic planning is an exercise in gathering and documenting information about the past, present and future of your business. Strategic planning helps determine where you want to go over the next few years, how you are going to get there and how to recognize when you’ve arrived.

Many BAs ask me where to get the business requirements when no one has done Enterprise Analysis or even a simple “

Many BAs ask me where to get the business requirements when no one has done Enterprise Analysis or even a simple “