Faultless Facilitation – Leveraging De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats

BA’s guiding, challenging, soft and squishy, crucial, and team-based conversations

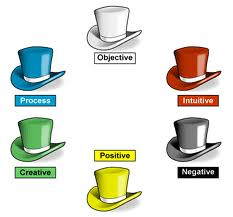

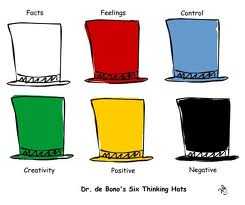

De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats

In my last post on facilitation, I shared some general principles for facilitating technical outcomes in software teams. Much of the focus was on creating just the right atmosphere so that team members shared their opinions and made thoughtful, team-based decisions.

In this post, I want to share Edward De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats model and how it can help you in facilitating much richer discussions surrounding your technical decision-making. But first, I want to share another facilitative model with you, though it’s more of a dynamic that occurs between individuals and teams who are trying to create new products, solve new problems, add features, or generally compete in their respective markets with creative solutions that drive customer value.

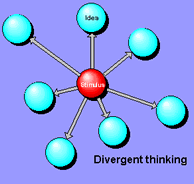

Divergent vs. Convergent Thinking

Divergent – many possible answers |

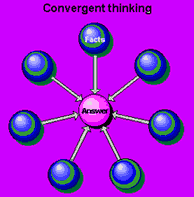

Convergent – one answer |

One way to think about any team-based discussion that needs to lead towards a decision is that it occurs in two phases. The first phase is focused on divergent thinking. In divergent thinking, you want to get ideas on the table, so consider this team-level process as equivalent to brainstorming.

When brainstorming, you want to get ideas and options on the table. You don’t want to judge, prioritize or analyze them. You simply want to generate as many as possible. If your divergent timeframe is too limited then team members will feel as if they haven’t had a fair sharing or vetting of their ideas.

As a facilitator, letting a team ramble on or throw around crazy ideas is a perfectly sound thing to do. In fact, if you don’t do it, it will lead to less buy-in and less permanent decisions. Quite often, you’ll want to leave half of your meeting time-box for divergent conversation in order to foster engagement across the entire team.

Then, mid-way through the meeting, you need to turn the discussions around and focus more on convergent thinking. That is, you want the team to start winnowing down ideas and converging on a single decision or at least a very small subset of options to decide upon later.

If you recall, I presented some decision-making tools in my last post. For example, as part of closing down or converging on an option, you could do some of the following:

- Vote on the options on the table; define loose, strong or unanimous majority before voting.

- Prioritize the options, keeping the top 2-3 in play for a second round of discussion.

- List pros/cons for each option, leading towards prioritization and elimination.

- SWOT (Strength, Weakness, Opportunities, Threats) analysis for the top 2-3 options, then discuss and converge on a selection.

- Select a decision-leader to lead the convergence discussion; if resulting discussion exceeds your time-box, decision-leader decides.

Usually, the above are led by the facilitator who is at the front of the room, actively collecting data from the team at a whiteboard or flip chart and converging towards a decision.

It’s this oscillation between divergent and convergent thinking that is the hallmark of good facilitation when making important or groundbreaking decisions. Striking the balance between over/under discussion and fostering a whole-team view is crucial. I usually allocate set times for divergent, interim, convergent, and decision-making close as part of this exercise, even allowing these themes to cross over multiple meetings.

Now that I’ve set the stage for this process, let’s move back to the thinking hats…

Back to the Thinking Hats

So what does this notion by De Bono have to do with team facilitation, and in particular, technical team-based decision-making?

Depth to our decisions

First, it gives us a breadth of perspectives to examine our options. For example, the White Hat is the data, facts and figures hat. If we were making a decision on database architecture to support our performance needs, it would be incredibly important for someone on the team to adopt the White Hat and mine the team (and customers, stakeholders and analysts) for performance-specific targets that are required for the architecture. In this case, hand-waving and conjecture isn’t helpful. What’s necessary is hard numbers and targets, something the White Hat perspective would foster and drive towards specifics.

Breadth or perspective to our decisions

As we’re reviewing and discussing something as a team, quite often we focus on a single or small set of the hats. For example, the Green and Yellow Hats often begin the discussion of new ideas or approaches for a specific design or architectural element, with Green driving the creative ideation part and Yellow the logic and positive part of the approach. If these two are the only hats that drive a decision, then the team missed four other perspectives in making their choice.

While this might not lead to a bad choice, the result will be narrowly conceived and narrowly considered. If someone on the team played the part of Devil’s advocate then they put on the Black Hat to consider some of the negative possibilities that could result from the decision. They criticized major and even minor points, trying to get everyone to consider this perspective and then respond with alterations or alternatives to the original design.

I like to think of each hat as testing the steel of an approach—tempering it and making it stronger. The more hats you use in your facilitation (divergent discussion, convergent discussion and decision-making), the broader your view is towards the problem and the broader your solutions.

Team-based influence

Quite often it’s difficult for some team members to raise issues in public. This is particularly evident in teams with strong personalities. Often, if a strong team member brings up an idea, say a Green Hat idea, many on the team will feel too intimidated to play Devil’s advocate or bring up any criticism because of the Green Hat member’s position in the team, their authority or their strength of personality.

The hats can actually dilute the personal nature of the commentary in these situations in that you’re not attacking the individual or their idea, but are simply putting on a hat and trying to fulfill its purpose. It abstracts individuals from personal engagement and quite often it strengthens their ability to bring out alternative positions that they would normally not be willing to do.

In practice, you see team members engaging the hats in this way. For example, if someone wants to bring up a criticism, they’d say, “as a Black Hat, I think the design lacks fault tolerance in the back end because of the limitations of the message-broker we’ve chosen…,” which challenges the idea and clearly not the individual.

The hats themselves

The hats often lend themselves to a flow of discussion. I’ve laid that flow out below in the order in which I present the hats themselves. Not that you have to precisely follow this flow, but it does have a sense of symmetry to it as you’ll see after going through it.

While I do recommend that you try and engage all of the hats, there are no Six Thinking Hat police that will come into your meeting, declare a violation and haul you away. Trust your team and use your best judgment in determining which hats are appropriate for a specific decision.

White Hat

Objectives; Facts; Requirements

Quite often, laying out the facts will help drive team decisions. In software, this often takes the form of requirements, use cases or user stories. White Hat discussion usually occurs in the beginning and rarely needs to be initiated. However, part of the hat is going back to the facts and refining them. In the case of functional requirements, perhaps look for tradeoffs and phasing to meet customers’ key goals.

Green Hat

Creative; Ideas

This is truly the brainstorming hat. In agile teams, this is the predominant hat, as the team works to be inclusive, respectful and attempts to get all viable ideas on the table. It’s the essence of planning and value poker as well where you get the teams’ opinions out in the open to drive discussion. This is also the creative hat, where different ideas aggregate into more creative solutions—the more the merrier.

Yellow Hat

Positive; Benefits

To use a common use case term, this is the “happy path” case for the requirement or the design that reflects the easiest implementation or has the greatest potential on the surface. It’s a great hat to explore early to gain momentum in your divergent thinking as many options will often surface for more analysis. The other side of this hat is exploring the benefit or potential of the idea—it’s business case or ROI.

Black Hat

Negative; Criticism

As I mentioned earlier in the post, the Black Hat or Devil’s advocate perspective can be incredibly useful in honing your designs and solutions. It usually refines the Yellow Hat perspective in the edge cases, creating a more robust, and error- and fault-tolerant solution. It’s also one of the most familiar of the hats for the team to leverage.

Red Hat

Emotional; Reactions

Quite often in software it’s not the logical flow that attracts customers or gets them excited. Usually, it’s something emotional or unexpected. The Red Hat is the one that reminds you to do customer focus groups and to do research within your U/X team so that you focus on those “delighters” that excite and gain an emotional reaction from your customers. It also exemplifies your gut feelings when making decisions.

Blue Hat

Rational; Conclusions

This is the decision process hat, so the facilitator often wears this hat by default. It also focuses on documentation, maintaining roles and responsibilities, and driving the teams towards conclusions. In the case of roles, this hat holds the team responsible for the role of who is responsible for architectural decisions, perhaps an architect or team leader, and who can weigh in with alternatives.

Wrapping Up

I hope you found this post and its predecessor useful. I also hope they inspire you to work on your facilitation skills—particularly if you’re part of an agile team. Why? Because many teams spin and spin around discussions and desperately need quality facilitation. I hope you can broaden your role to help fill this need.

I’ve found that Edward De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats model can truly help your facilitation within your teams by fostering depth and breadth in your decision-making. For now, I sincerely hope your decisions improve in their quality!

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.