Recruitment Metrics for BA Teams

Being involved in BA recruitment is a big responsibility. It’s hard to recruit right now, and it’s easy to blame the competitive market and skills shortage. It’s tempting to leave measurement and metrics to HR teams, but there are a number of key concepts all those involved in BA recruitment need to understand.

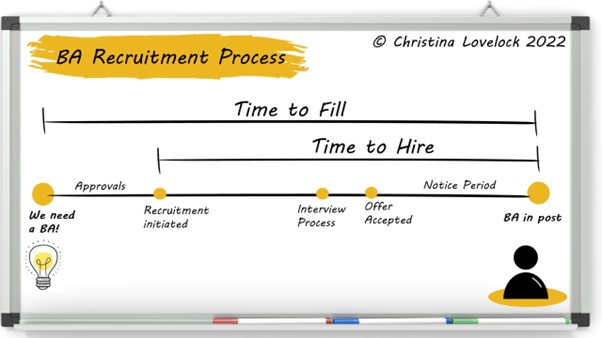

Time To Fill

From the point we become aware that a new or replacement BA role is needed, a clock starts ticking. Whether someone has handed in their notice, or a new project has emerged, we now have a gap that needs to be filled. It is so important to understand our average time to fill (TTF) for each role on the BA career path, as this aids decision making, including the use of short term resources such as consultants, contractors and secondments.

Typically more senior roles take longer to fill, because the talent pool is smaller and the demand greater. Having internal talent pipelines reduces the TTF and creates internal progression routes and clear BA career pathways. Ensuring these are in place improves knowledge retention, employee loyalty and morale and serves as an attraction factor for BAs outside the organization.

TTF includes internal processes of gaining agreement and approvals, getting a role posted and engaging with recruiters. This is often a hidden time over-head, and usually an area where organizations can speed up their recruitment.

Time To Hire

This marks the time between making a role available for applications and having someone in post. It includes the interview process and the notice period of the candidate.

Recruiting managers often put pressure on candidates to try to reduce their notice period. This is unfair, when it is the only period of time in the whole process which is outside of the recruiting organizations’ control. If we want people in faster, we should look to improve our own processes! Sometimes organizations exclude notice periods from their time to hire metric, to stay focused on the elements within their control.

Knowing the average time to hire helps us keep stakeholders informed, and contributes to better planning and onboarding.

Advertisement

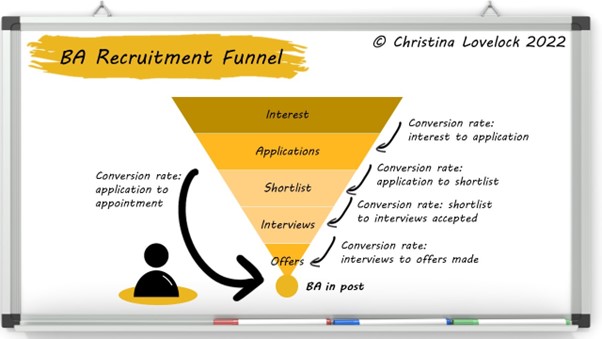

Conversion

At each stage of our recruitment process people drop out or are ruled out. This can be visualized as a recruitment funnel. Understanding the conversion rates between different steps in the process allow us to answer question such as:

- How many applications do we typically need to find one appointable BA? [conversion rate from application to accepted offer].

- How many candidates accept our offer? [conversion rate from interview to accepted offer].

- What can we do to improve our conversion rates? (Faster processes? Better marketing of roles? Better communication with applicants?…)

If we understand where in the process we are losing people, and really consider the candidate experience, we increase the chances of a successful recruitment outcome, and save both time and money. Different organizations have different levels of formality, and may include more or less interview rounds and steps in the process. However formal or informal, it is valuable to understand the key conversion rates.

Attrition/Turnover

This is the rate which we lose BAs from the team over a given period. Not all attrition is bad, we need to support people to move to new and appropriate roles, and we need to allow BAs with new ideas and different experiences to join the team. Generally an attrition rate of less than 10% is considered healthy for team stability and business continuity.

Retention is the opposite measurement to attrition. This is the percentage of the team that stay during a given period. Focusing on ‘increasing retention’ is a more positive framing of the issues than ‘reducing attrition’. Recruitment is expensive, the cost of replacing BAs is far more than the cost of investing in appropriate initiatives which retain talented BAs in the organization. By asking and listening to what individual team members want from their role and employer we can increase retention rates (money will be a key factor, but not the only one!).

Tenure

This means understanding how long people stay with us and can be considered at different levels:

- Average length of time in each role/grade within the BA structure

- How long people stay within the BA team

- Total amount of time spent within the organization.

This is helpful to understand the rates of progression within the team. If we have entry level/development roles within the team, how long before people typically progress to a practitioner role? It allows trends and patterns to be explored. If we find people either stay less than 1 year or more than 10 years, what insights can be gained? What does that tell us about our recruitment and retention processes?

With further analysis we can understand the push and pull factors which keep BAs within the team or encourage them to look elsewhere. It also allows us to consider what internal development routes we offer into related professional disciplines.

Conclusion

In this competitive market, with increased demand for business analysis skills and the ‘great resignation’ making people consider their options, BA teams need to fully understand our own processes and look for improvements. A greater focus is needed on recruitment and retention, and we can no longer rely on ‘recruiting as we always’ have to make great appointments and grow our teams.