What makes business analysis on a project effective?1 Is it just about allocating a business analyst (BA) to the project to produce business analysis deliverables on time, or is it about effectively communicating and engaging with stakeholders? While both are tactical prerequisites, we believe that engaging with stakeholders is key to any effective project implementation.

Research proves that, in the long term, effective stakeholder engagement is good for any business.2 Organizations with a greater awareness of stakeholder interests and higher stakeholder engagement patterns are more likely to avoid crisis, simply because they’re in a better position to leverage opportunities and anticipate risks.3 Several compelling studies across industries on the impact of good stakeholder relations demonstrate that, over time, organizations focusing on building stakeholder trust are more resilient across indicators of value such as financial resilience, sales, cost reduction, time to market and control of operating costs.3, 4

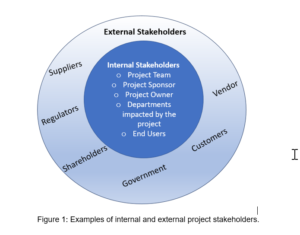

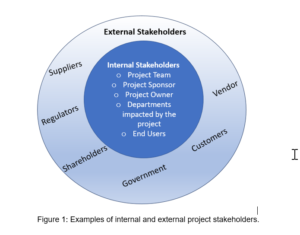

So, who are the stakeholders? Stakeholders are individuals, or groups of individuals, who either care about, are actively involved in or have a vested interest or a stake in the project’s success. They can also affect the project BA’s ability to achieve his or her own goals.5 Stakeholders can be internal or external.

Internal stakeholders may include top management, project team members, a BA manager, peers, a resource manager, end-users, and internal customers/delivery partners. External stakeholders may include external customers, governments, contractors and subcontractors, regulators, and suppliers/vendors.

Stakeholder engagement is the practice of interacting with and influencing project stakeholders to drive the overall success of an initiative. Stakeholder expectations and perceptions, as well as their personal requirements, concerns, and agendas, influence projects, determine what success looks like, and impact the achievement of an initiative’s overall outcome. Successful stakeholder engagement is vital to effectively delivering value on a project.

Whether internal or external, the first thing to identify is whether BAs effectively engage with project stakeholders. This paper explores different levels of stakeholder engagement and the approaches that will enable a productive association and result in project success. Typically, stakeholder engagement falls into three broad models: high, moderate, and low engagement.

Advertisement

High engagement model

Stakeholder engagement is at its peak, in this model, meaning that BA and stakeholder thought processes align on project objectives, definitions, and benchmarks of success. They work in tandem to drive the project to its intended conclusion in an efficient and timely manner. This model is highly interactive. Ideas and suggestions from both sides are exchanged to evaluate the pros and cons and resolve any differences of opinions objectively through a process of mutual consensus. There is mutual respect, trust, and a sense of ownership over the decisions being made and risks being taken.

In short, this is the ideal scenario. In this engagement model, the stakeholder clearly communicates expectations, actively participates in project requirements, promptly responds to questions and communications, and engages with the BA and shows genuine interest in the analyst’s work.

Best practices to help a BA sustain high stakeholder engagement

- Work to become a BA on whom stakeholders can depend. Build relationships based on trust.

- Demonstrate awareness of project timelines, efficiency and cost-related issues while prioritizing the needs of the project.

- Maintain regular communication. Keep stakeholders informed of project progress and BA deliverables.

- Address constraints and challenges on time. If there are time constraints or other challenges, meet stakeholders formally or informally (in-person or virtually) to discuss the issues and get their buy-in for feasible solutions.

- Listen to and address stakeholder concerns in a timely manner.

- Keep stakeholders engaged by involving them throughout the project. Always ask for stakeholder input and work toward implementing what’s possible.

- Recognize stakeholders’ achievements and appreciate their support.

Moderate engagement model

Stakeholder engagement is average in this model, meaning that the BA and the stakeholder agree on the vision and objectives of the project but don’t understand the impact their respective actions might have on its timelines and success. They work on the same team but don’t always collaborate, attend meetings but don’t actively participate, provide input and feedback but not in a timely manner. In this model the stakeholders aren’t clear on the BA’s expectations and deliverables. In other words, to achieve a higher level of engagement it requires active collaboration and participation between the BA and the stakeholder.

So, there is hope with this model. But if the BA doesn’t work to improve the relationship, things are likely to quickly reach a point from which it will become harder to recover.

Best practices to help a BA improve the stakeholder engagement level

- Drive conversations and meetings that are interactive, constructive, and engaging for both parties.

- Communicate effectively to engage stakeholders. Leverage collaboration tools and continuous brainstorming workshops that enable stakeholder participation.

- Set realistic expectations with stakeholders from the onset of the project.

- Be mindful of and flexible to accommodate stakeholders’ schedules and preferences. This includes engaging with stakeholders formally or informally, as well as during work or off hours.

- Listen to, heed, and execute stakeholders’ feedback and demonstrate its impact on the project.

BAs can leverage several tools and strategies to enhance stakeholder engagement (see Table 1). Once they understand the project, they will become more receptive to what a BA has to offer. And then they will want to know how the initiative will be implemented, whether and how their concerns will be addressed, and how they can contribute to the solution.13 At this stage, it’s important for BAs to manage the relationship to set the right expectations and agree on roles without losing the already established level of engagement.

| IIBA BABOK® Guide Technique |

Purpose |

| Functional decomposition |

Explains key components of business analysis to create transparency within an initiative, specifically in how a BA works and the role stakeholders can play. |

| Mind mapping |

Enables BAs to gather and summarize participants’ thoughts and ideas, as well as any ancillary information, and then determine interrelationships. |

| Process modelling |

Defines the solution and describes how the business analysis will be executed. This technique can include actors and information flows to illustrate what’s expected of each stakeholder during various stages of the process. |

| Roles and performance matrix |

Maps each stakeholder’s role and permissions across business analysis activities. For example, which stakeholder will shape what part of the solution, approve the solution design and implement the solution. |

| Stakeholder list, map, or personas |

Documents stakeholder responsibilities, defining how each will shape the solution and all will collaborate. |

| Brainstorming |

Fosters creative thinking around project challenges and possible solutions. The goal of brainstorming is to produce new ideas and derive themes for further analysis. |

Table 1 – IIBA Reference 5,6

Low engagement model

Stakeholder engagement is below average in this model, meaning that BA and stakeholders thought processes don’t align regarding project objectives, definitions, and benchmarks of success. The BA and stakeholders don’t work in tandem to drive the project to its intended conclusion in an efficient and timely manner. In this model, there’s no constructive exchange of ideas and suggestions with the objective of evaluating the pros and cons. Differences of opinions aren’t resolved objectively and lack mutual consensus. Respect is a lacking and there’s no sense of ownership of decisions being made and risks taken.

This results in conflicting requirements and deliverables, delayed project timelines, dissatisfaction on the project progress and eventual failure to meet expectations. In this engagement model, the stakeholder:

- Asserts authority

- Doesn’t actively participate in meetings

- Provides minimal to no feedback

- Quickly critiques deliverables

- Resists change

At the beginning of the project, especially a change initiative, there may be resistance for various reasons.6 Chief among these is fear. Because the business case behind a change initiative is often restructuring, reducing headcount, or introducing automation — all of which may lead to the loss of some jobs — people will naturally be concerned. That may lead some people doubt their ability to develop new skills, learn new things or maintain an acceptable level of performance in the new system. Projects that lack clarity at the start are also concerning. While it’s always difficult to anticipate the direction of a change initiative, in the early phase, most stakeholders aren’t sure of their role or how or where they’ll fit in the overall process. And without established norms or processes in place, an initiative is almost always likely to change the environment. At times it’s this discomfort, or a lack of justification for this change, which causes resistance.

Remember: Be prepared. Be flexible. Be ready to escalate.

To overcome these and other challenges, we recommend the following steps:

Step 1: Be Prepared

Send the agenda and any relevant documents prior to the meeting so that everyone has an opportunity to prepare for the discussion. Arrive in the meeting room (physical or virtual) a few minutes early, especially when the BA is the host. Follow the best practices for virtual audio/video calls, especially in a remote work setting.7 Invite a person of authority to the meeting for support. This could include the BA’s manager, the project manager, or a business process consultant. Be active rather than reactive in any situation. For a BA, it’s always important to take a few minutes before responding to an email or conversation. BAs should never take feedback personally and always be willing to reach out to their peers, core team or leader for help.

Step 2: Be Flexible

Accommodate the stakeholders who aren’t available to meet in person and in this case, the BA should try to address stakeholder requests by scheduling a conference call. If meeting during prime business hours is not possible then connect with stakeholders during off-hours or different times of the workday, within stipulated/acceptable business hours. This sort of availability supports a more informal setting, which in turn encourages stakeholders to share their concerns. It also demonstrates that a BA is eager to engage with stakeholders and understands their viewpoint. It will help the BA gain stakeholders’ trust and make them feel their voices are heard and their perspectives factored in.

Step 3: Be ready to escalate

Invite a person of influence — for example, a hardline manager or project manager — to meetings with stakeholders to get better guidance on how to maneuver the project as well as keep the manager informed of progress. Stay calm and objective throughout the process. Under no circumstance should a BA feel the need to pressure stakeholders on any matter since such behavior will only aggravate the situation and result in further damage to the relationship with stakeholders.

Our recommendations for a successful engagement model

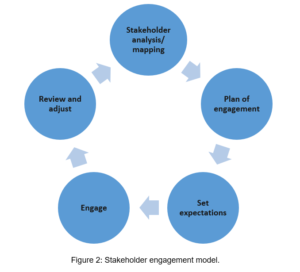

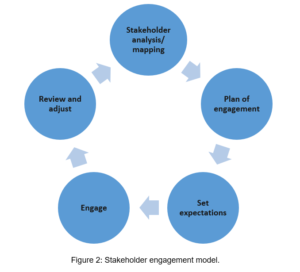

We recommend the following engagement model that has been tried and tested and has resulted in successful and long-standing engagements with our stakeholders over the years.

Stakeholder analysis/mapping. Analyze stakeholder needs and expectations and think about how the project or the proposed change might impact stakeholders, as well as how they can impact the proposed change. Based on this analysis, select an engagement approach that best suits stakeholders’ needs for effective communication and collaboration.

Plan of engagement. Plan an effective approach to stakeholder engagement. The goal is to select an approach that will ensure the highest level of engagement throughout the initiative. Things to consider when selecting an engagement approach may include:

- Style of communication during meetings. Keep the meetings interactive. Initiate and foster maximum participation.

- Frequency and duration of meetings. Schedule short meetings with an agenda. When meetings are too long, participants lose their focus.

- Format of meetings. Schedule virtual or in-person meetings as appropriate.

Set expectations. Set and communicate expectations with stakeholders. Make sure the desired outcomes are clear and well understood by the stakeholders. For example, if BAs request input on requirements, then they need to make sure that:

- Documentation is sent to stakeholders on time, preferably well in advance of the request for feedback.

- Documentation includes anything stakeholders may need, such as reference documents, process flows, data elements or use cases.

- A timeline is set for when the BA expects feedback.

Engage stakeholders. Keep the focus on maintaining and improving the level of engagement. Keep stakeholders engaged through:

- Maintain the frequency and level of communication. Keep stakeholders apprised of the progress and possible challenges.

- Active listening. Listen to stakeholders’ concerns and feedback and address them accordingly.

Review and adjust. Review and adjust the plan based on stakeholders’ engagement and feedback. Revisit the approach and adjust for future interactions to maintain the level of stakeholder participation and involvement.

Conclusion

The general rule for any stakeholder engagement is the understanding that stakeholders care about their responsibilities and want to do their best. Despite that, there may be certain obstacles that prevent successful and beneficial stakeholder engagement. In that case, BAs will find it helpful to analyze the initiative to understand the cause of the roadblock and find a way to resolve it as early as possible. Handling the situation objectively and the demonstrating the initiative’s roadmap — including a clear picture of the initiative, its impact, and everyone’s roles — fosters a collaborative environment that will lead to a successful project.

Sources:

1 “ The Habits of Effective Business Analysts.” https://medium.com/analysts-corner/the-habits-of-effective-business-analysts-c9b7d9786f8b

2 “Long term business health stakeholder theory.” https://backlog.com/blog/long-term-business-health-stakeholder-theory/

3 Enright, Sara; McElrath, Roger; and Taylor, Alison. 2016. “The Future of Stakeholder Engagement.” Research Report, BSR. https://www.bsr.org/reports/BSR_Future_of_Stakeholder_Engagement_Report.pdf

4 Witold J.Henisz, Sinziana Dorobantu and Lite J. Nartey. “Spinning Gold: The Financial Returns to Stakeholder Engagement.” Strategic Management Journal. 2013. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/smj.2180

5 International Institute of Business Analysis. “A Guide to the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge® (BABOK® Guide).” https://www.iiba.org/standards-and-resources/babok/

6 Rahul Ajani. “Engaging Stakeholders in Elicitation and Collaboration.” International Institute of Business Analysis. https://www.iiba.org/professional-development/knowledge-centre/articles/engaging-stakeholders-in-elicitation-and-collaboration/

7 Ken Fulmer. 2020. “Working Virtually – 10 Tips for Management.” https://www.iiba.org/business-analysis-blogs/working-virtually-10-tips-for-management/

Further reading

Ori Schibi. “The role of the BA in managing stakeholder expectations.” Project Management Institute. October 26, 2014. https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/role-ba-managing-stakeholder-expectations-9367

Kenneth W. Thomas. “Making Conflict Management a Strategic Advantage.” Psychometrics. http://www.psychometrics.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/conflictwhitepaper_psychometrics.pdf

Robyn Short. “The Cost of Conflict in the Workplace.” Robyn Short. February 16, 2016. http://robynshort.com/2016/02/16/the-cost-of-conflict-in-the-workplace/

Association for Project Management. “Communicate: the first principle of stakeholder engagement.” https://www.apm.org.uk/body-of-knowledge/delivery/integrative-management/stakeholder-management/

Ian Haynes. ” 4 Strategies for Dealing With Difficult Stakeholders.” wrike. September 25, 2020. https://www.wrike.com/blog/4-strategies-dealing-difficult-stakeholders