5 Killer Questions Types For Digital Transformation

A recent article concludes that for an organization to get the desired results from their digital initiatives,

such as data analytics, predictive analytics, machine learning, AI, etc., data scientists have to ask the right questions.[i] The article was written as a guide for data scientists to help them ask questions to get at the business decisions needed to be made when developing predictive models for these applications.

However, the article’s questions are stated in a way that might cause even the most informed business stakeholders to scratch their heads. If most decision-makers can’t answer them knowledgably, what can the organization do? Get BAs involved, of course! Having a BA participate in the question and answer sessions can alleviate a great deal of misunderstanding and help ensure success with digital projects.

This article imagines that for each of the 5 question types, there is a three-way conversation with a data scientist, a business decision-maker, and a BA. The questions the data scientist asks are from the article, which the BA rephrases to be more easily answered.

Type 1 – Alignment with the organization’s goals and strategic direction

Data scientist to business stakeholder – First things first. What exactly do you want to find out with this digital effort?

Business stakeholder to data scientist – I’m trying to predict sales of a new product we’re thinking of launching.

Business analyst to business stakeholder:

I’m sure this project can help with that effort. But before we talk about specifics of the types of information you’re looking for, what is the business need for this effort? That is, what problems are you trying to solve? Let’s make sure this initiative, which is not going to be an easy undertaking, will address your need. Perhaps there is a quicker, less costly way to achieve your goals. And I have some related questions that will give us more context:

- How does this effort align with the strategic direction of the organization?

- What are does the organization do well that will help ensure the project’s success and minimize risks?

- How will this project help overcome some of the things we don’t do so well?

- What opportunities are out there and how can the organization take advantage of them?

- What should we be worried about? How are competitors, for example, doing with their digital initiatives?

Type 2 – Scope of input needed to create and train models

Data scientist to business stakeholder – Where will your data come from?

Business stakeholder to data scientist – I’m sorry, I don’t know the names of the specific databases. I thought I was here to make business decisions, not answer questions best answered by the IT folks.

Business analyst to business stakeholder – At this point we don’t need to know the names of the specific databases. What we mean by where the information will come from are things like:

- Which business areas will be involved in this project?

- Which stakeholders will have input into the decisions affecting the creation of the models?

- Given that this effort will affect divisions in different parts of the world, who will establish the business rules?

- What types of information will come from other sources, like social media and Google analytics?

Type 3 – Data presentation

Data scientist to business stakeholder – What data visualizations do you want us to choose?

Business stakeholder to data scientist – I’m sorry, I don’t understand what you mean. Do you mean like how I want to see the data? If so, I don’t know. What are the possibilities?

Business analyst to business stakeholder – There are a lot of tools that will take the data and interpret the results for you. They help you make sense of the tons of data you’ll be presented with. They can help you analyze data, point out anomalies, and send out alerts that you specify. They can be in the form of charts, dashboards, or whatever, but keep in mind that if they are hard to read, they will be meaningless to you. I can show you some examples and the pros and cons of such things as animation and use of images, but first let’s talk about the information itself.

- What results are you hoping to get?

- What type of predictions about your customers would be helpful? Your products?

- What types of trends would be helpful to you in making business decisions?

- What types of exceptions do you want to be alerted about?

- What information do you want that’s actionable vs. historical?

Type 4 – Statistical analysis leading to the desired outcomes

Data scientist to business stakeholder – Which statistical analysis techniques do you want to apply?

Business stakeholder to data scientist – Well, statistics is not my strong suit. What are my choices?

Data scientist to business stakeholder – Regression, predictive, prescriptive, and cohort, and there are others, like descriptive, cluster.

Business stakeholder to data scientist – blank stare

Business analyst to business stakeholder – Maybe I can help here. These types of statistical analyses have a number of similarities. They include use of historical data, algorithms, models to train the machines, and business rules. Not to oversimplify and at a very high level, all predictive models make use of historical data and algorithms to predict future outcomes.

Here are questions based on examples of different outcomes using different statistical analysis:

- What groups of customers do you want to target? Cluster analysis classifies data into different groups and can help you target certain customer groups.

- What types of trends do you want to track? Cohort analysis allows you to compare how groups of customers behave over time.

- What kinds of recommendations might you want as a result of the analysis? Prescriptive analysis not only predicts future outcomes, but it will “prescribe” or recommend the best course of action.

So to answer the question we need to understand what you’re trying to accomplish. We’ll let her (nodding to the data scientist) figure out the most appropriate analysis method and tool.

Type 5 – Creating a data-driven culture

Data scientist to business stakeholder – How can you create a data-driven culture?

Business stakeholder to data scientist – We already have a data-driven culture. Everyone in this organization understands how important data is to our ability to survive as an organization.

Business analyst to business stakeholder – This might be more complex than it first appears. In order to use historical data, which we need to do regardless of the chosen algorithms, it needs to be cleansed. Cleansing is needed to make the data predictive, and cleansing data takes lots of time and money. And it’s the last thing anyone wants to do. So I have some questions for you:

- What’s the organizational commitment to cleansing dirty data?

- Who will decide how clean the data needs to be? How clean is clean enough?

- Who will decide who owns the data when the same data exists in multiple databases? In order to get the outcomes we want, there needs to be one single source. If the same data exists in multiple databases, someone needs to be its sole owner.

In sum, we’ve provided questions within 5 question types. However, to be effective, we BAs need to learn as much as we can about the digital world—about the world of digital transformation and what it means for the organization. We need to immerse ourselves in research and journal articles and think of how to make sense of it for our organizations. We need to think of digital projects from both the data scientist and business perspectives. And we can do that. After all, we’re BAs and that’s what we do best.

[i] Your Data Won’t Speak Unless You Ask It The Right Data Analysis Questions, By Sandra Durcevic in Data Analysis, Jan 8th 2019, https://www.datapine.com/blog/data-analysis-questions/

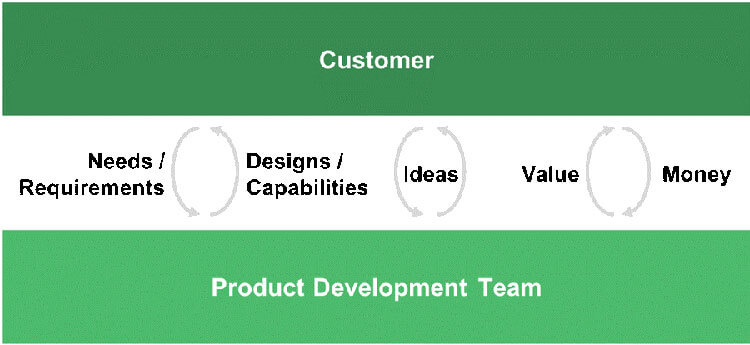

I propose that if something isn’t visible in the exchange at the Customer Membrane, then that “thing” is not particularly important. For example, if the team has decided to use an obscure programming language in the back-end of their cloud-based solution, this doesn’t matter to the Customer. So let me repeat this in bold print for emphasis:

I propose that if something isn’t visible in the exchange at the Customer Membrane, then that “thing” is not particularly important. For example, if the team has decided to use an obscure programming language in the back-end of their cloud-based solution, this doesn’t matter to the Customer. So let me repeat this in bold print for emphasis: