The user story has nearly become the ubiquitous requirements artifact in Agile contexts. User stories have had much written about them, their format, how to write them, the associated acceptance tests, and more.

As for acceptance tests, we’ve moved beyond writing them to articulating them as “executable tests” in tools such as Cucumber and Robot Framework.

All of this evolution has been great, as is the focus on the collaborative aspects of the user story.

But I’m starting to see something troubling in my coaching travels. I think we might be focusing too much on the user story as an Agile requirement artifact. Instead, we should be taking a step back and considering the user story as a much simpler communication device.

That is simply as a STORY, and much less as a written story, but moreso as a story told face-to-face.

Imagine

In fact, as I’m writing this, I’m envisioning the quintessential storytelling scene where a group of scouts is in the woods, surrounding a fire, late in the evening. And the Scoutmaster is recounting a story to them. It’s usually a scary story, intended to entertain, but also raise the angst of the listeners.

As the story continues the scouts lean forward. Their pulse increases and they begin to hear noises in the surrounding woods that raises the hair on their arms. They become a part of the story. It becomes real to them, and they can envision the words. In fact, for a short time, the story becomes their reality.

I believe this is the sort of intention that Kent Beck had for user stories when he initially created them. It wasn’t a requirement, but instead it was an engaged conversation between the team and their client.

It was intended to get the client or stakeholder to sit down with their team and share their vision in a storytelling fashion. It was intended to be collaborative, with ideas being shared, and questions being asked. As the discussion unfolded, the team would become intimately familiar with the client’s challenges or problems that they were trying to improve.

And instead of telling the team what to deliver, they simply shared their perspectives. And the team would respond with empathy and understanding around how to implement things to help their client. In fact, they also started thinking of the experiments they might run to narrow any gaps in their understanding.

If that was the original intent, let’s start to look at some of the aspects of potential storytelling within agile teams.

Put The Client First

The more we can envision the client and their context, the better the team will be able to implement solutions that will solve their challenges and ultimately surprise and delight them.

Tell stories about your clients. What is their motivation? What is their environment? What is their experience level? Who are they – specifically? And importantly, what problems are they trying to solve with their requests?

Related Article: 50 Ways to Write a Great User Story

Find out what excites them and what doesn’t. Don’t just explore their immediate needs, but try to understand their future challenges and where they might be in a year or more.

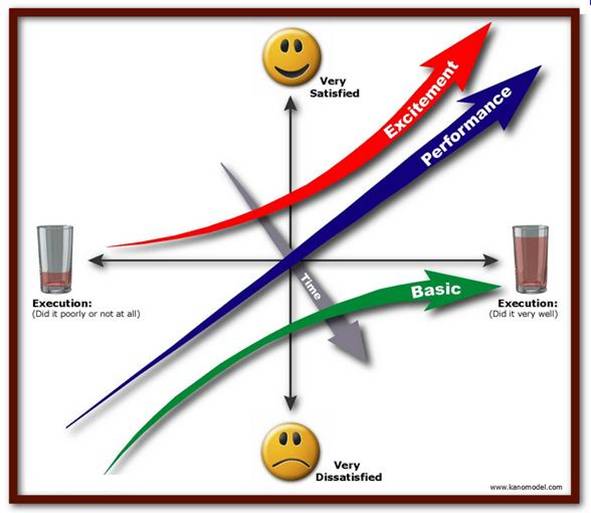

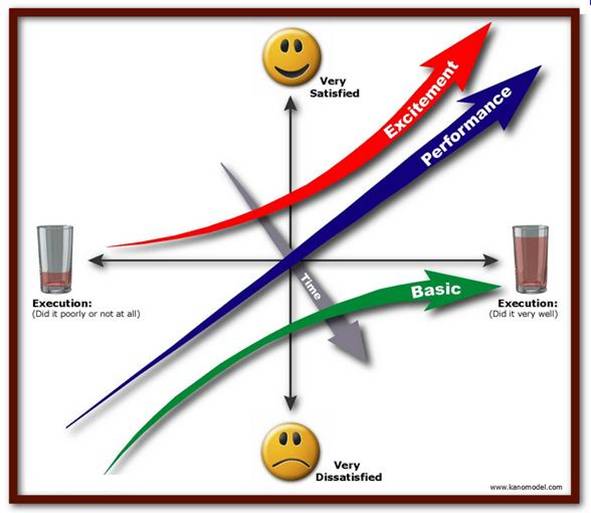

The Kano Model talks about three basic categories of customer needs:

- Delighters or Exciters – the WOW factor in a product or application.

- Basic Needs or Must Have’s – these are “table stakes” for the product.

- Performance or Linear – the more of it, the better.

These three types of customer needs are mapped against how satisfied the customer’s reaction to them are AND against the execution and quality delivery dynamics of the team.

Better than talking about the client, invite them into your team. The more direct the communication, the better. And using a model such as Kano to explore their reactions to features, priority, impact, and need can be powerful. Not only in deciding what to build and when to build it, but the conversations around Kano are even more powerful.

Here’s my reference to Kano – http://www.agilebuddha.com/agile/faster-time-to-market-or-lower-cost-of-development-is-a-delighter-anymore/

The Backstory

Quite often there are a series of reasons why your clients are asking for a software feature. Some of them are driven by business needs. Others are more contextual, for example, an older system is so aged that it no longer meets their needs. Or they need the functionality, but in an upgraded, more maintainable “package”.

Often the backstory is unsaid, and you’ll need to “tease it out” of your clients, stakeholders, or customers.

You also need to push through the first reaction, which is often – I need it because I need it. You’ll need to patiently “dive deeper” into their thought processes and motivations.

One effective way to do this is observation. Asking the customer to show you what they do today, which might give you insights into why they are requesting something new. For example, if they show you that their current process is slow or unwieldy, then speed and simplicity will be paramount.

Another way to explore this is by demonstration. Showing them simple paper and code prototypes that cost very little to build, to get their reactions and feedback. No matter how we do it, we have a responsibility for exploring the drivers behind our customer’s requests.

Now I want to switch gears a bit and explore some of the crucial tactics of our storytelling.

Tactics of Story Telling

A Good Introduction

Often it is quite useful simply to get to know your customer. What is their name? What is their job title or role within the company? Another point is their experience level? Before jumping in to say – how do you want this function or feature designed, stop and get to know them.

And this includes introducing yourself and sharing what motivates you as well. Come to a place where you’re simply getting to know one another to improve your ongoing relationship. Spend some time together and, most importantly, observe, ask open-ended questions, and deeply listen.

Motivation

I’ve watched actors prepare for their roles or scenes in plays, and a topic that often comes up is “their motivation”. The actress explores the role and the events and experiences leading up to the current situation or context.

Often the actress tries to connect the situation to their experience and history so that they can better understand and express the moment for the audience.

Another way of describing this is the WHY behind the request. In his book Start With Why, author Simon Sinek explores how effective leaders start with the why behind their goals. In other words, exploring what they’re trying to achieve. I think effective Product Owners do the same thing, instead of simply making a request for a feature; they first start with the reason behind the request.

Visualization

I’m an avid reader of Science Fiction and Fantasy novels – particular the fantasy genre. One of the things that set great authors apart from good authors is their ability to develop a world that you can visualize. Often they are developing an entire world full of cultures, races, geographies, families, histories, characters, and a dichotomy of good versus evil.

As I read, I can often visualize the world, both the things that the author has established, but also start to add my imagination to the environment and context.

User stories need to invoke the same. They need to encourage the reader or listener to leverage their imagination. To ask questions based on what’s already been shared. Or better yet, to make suggestions about how something might unfold or look to the user.

Whiteboards are particularly useful in this. I love it when during storytelling the team gathers around a whiteboard some various individuals start drawing and visualizing options.

Filling in the Blanks

Often a good story doesn’t simply give you the plot. Instead, the plot unfolds with twists and turns. In fact, in a good whodunit, you rarely know who the villain is until the final pages. You’re left trying to “figure things out” during most of the story.

It’s this mystery or intrigue that often makes the story compelling to the reader (or listener).

I believe one of the reasons that user stories are intended to have holes or are “intentionally vague” is to encourage the listeners to fill in the blanks with their experience and intuition. This is a powerful way to activate the whole team’s creativity.

Excitement

A good story should draw the listener into the moment. It should catch their attention and ultimately, generate some energy and excitement.

And you don’t have to generate that excitement all at once. I think stories are often iterative in nature. You start telling it, and you run out of time. So you let the listener “stew on” or think about the story for a while. Let them start to make it their own story, which is ultimately the goal of the storyteller.

Empathy

I think of empathy as putting yourself “in the shoes” of another. It’s not simply a role-play or a thinking exercise. It’s a deep and committed effort to put on the mindset of your customer.

Often interviewing and observation can help here. I remember when I was at iContact all of us in the engineering team would spend 2-3 hours per month sitting with our customer support staff listening to customer calls. Amongst many benefits, it phenomenally increased our empathy for our customers AND our support staff.

And it improved our product quality too.

Success

One of the cool things about acceptance tests or acceptance criteria is that they help define what done and what success looks like for a user story. That’s a very useful concept.

Often in our storytelling we want to not only share what we want but even more importantly, what we don’t want or need. This clarity of boundaries can help the team stay focused towards a solution and not fall into the trap of gold plating.

Next Steps

Of course each story should result in actions and follow-up. Or I should say that it inspires action. There should be a visceral sense of what to do next and momentum to go out and start implementing it.

In fact, when we deliver the story, we should also include the backstory that we heard that led us to the implementation or solution. And that’s just the closing of one chapter of the story.

Wrapping up

As part of my writing efforts, I often tell or share stories. One critical aspect to it is that they have to be real and relevant.

But I have this feeling that it’s one of the best ways to convey information to my readers – to make my lessons real, and to have it resonate to the readers “real world”.

I’m not saying I’m the best storyteller. I’m certainly not. But the act of storytelling is one of the richest ways to communicate that I’ve found.

I hope I’ve inspired you to look at your user stories in a different way and to increase your attempts to tell your stories.

Stay agile my friends,

Bob.

PS: after I write this, I discovered a brief article by Brian Hoadley on LinkedIn where he explored – Understanding the Importance of Narratives in My Work. While it’s UX-related, I think it nicely compliments this article

Shane Hastie

Shane Hastie Angela Wick, CBAP, PMP

Angela Wick, CBAP, PMP