We’re in Orlando for a working session as part of the Core Team building BABOK V3 and over dinner this evening we got to discussing the relationship between user stories and use cases (it wasn’t the only thing we discussed, we are also a social group ;-)).

We noted with concern that there have been a number of recent discussions (client, articles, blogs and general industry) of using both User Stories and Use Cases at the same time in Agile projects. This seems to us (with general agreement around the table) to be both a waste of effort and actively against the Agile philosophy of doing the simplest thing that will work and deferring the detail until just ahead of when the component of the product will be built.

We would like to outline the basic differences, considerations and risks of using this approach. Even it is seems to be a trending topic, we would like to fill the gap in addressing beyond the trend and move towards the practically and risks of using Use Cases on Agile projects.

Differences and Similarities

So what are the differences and similarities between User Stories and Use Cases, and when do we recommend using the different tools?

Use Cases

A Use Case is “an end to end sequence of interactions between an actor and a system that yields a result of observable value to an actor, usually the instigating actor”. Um, so what does that actually mean? Generally a Use Case (the textual description, not the stick figure diagram) is written as a flow or sequence of steps in the format

Actor does something

System does something

Actor does something else

System does something else

…

A Use Case is made up of one main flow and a number of alternate and/or exception flows some of which can branch back to the main flow.

Now Use Cases are by nature fairly detailed – they describe the steps in an activity and the points in the flow where things can change. To produce a useful (can be given to someone to build from) Use Case you need to define the set of interactions in quite a bit of detail, you need to understand what the business rules are that govern the activity, the options that the actor will have available to them when undertaking the activity, the ways things could go wrong and what bits of information are needed in the flow of interactions. To do this you need to spend quite a bit of time and effort analysing the activity and producing the document. This is BDUF – Big Design Up Front which is the antithesis of Agile.

User Stories

User Stories were originally a reaction to this big up front thinking. When Kent Beck defined eXtreme Programming (XP) he came up with the concept of a User story as a tool to support the iterative and incremental approach which is inherent in all the Agile methods. Mike Cohn went on to write a book which explained what User Stories are and how they are used in Agile projects. In addition to these two, Jeff Patton publicized the technique of Story Mapping to show how User Stories can be used to cover the breadth and depth of functionality needed in a product.

The key to writing good User Stories is to understand that the intent is not to provide the detail early on in a project, but to provide a framework where the detail can be added as it is needed, just enough and just in time. Drawing on the work of Beck, Cohn and Patton and many others the generally accepted approach to producing User Stories and using them to guide the development of the product follows a decomposition approach.

The decomposition comes in the form of a story map. The beginning of a story map is defining the Backbone stories – the key User Activities or Tasks which need to be accomplished to do the work of the product, the large discrete chunks of functionality which need to be delivered to be able to say we have solved the problem. These large chunks are often referred to as Epics (a big story ;-)), they equate to an elementary business process, something that is done in one place, at one time, by one person. Comparing this to Use Cases, this would be the result of the Use Case survey – a list of the discrete elements of the product, goals of the actors.

When building a story map, these Epics are normally laid out in a single row showing the logical sequence and handoffs between the steps in the process. Visually these Epics will be written on a different colour card to t e User Stories which will come later.

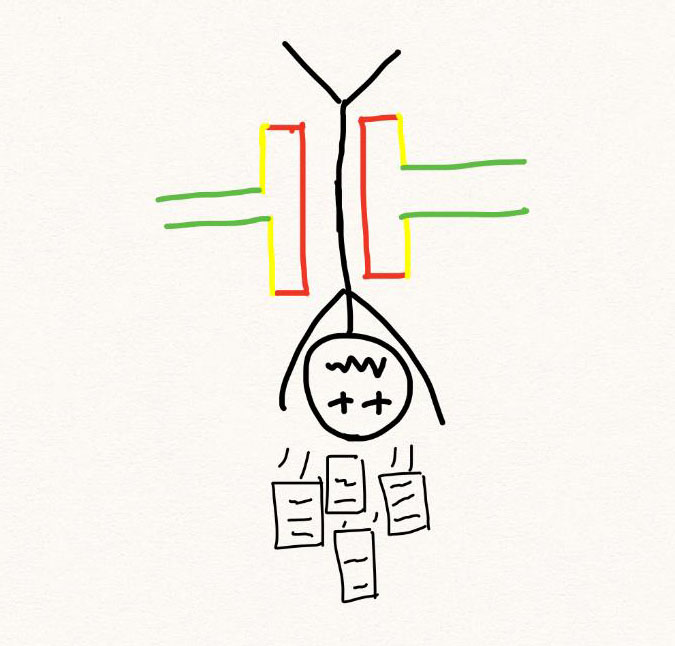

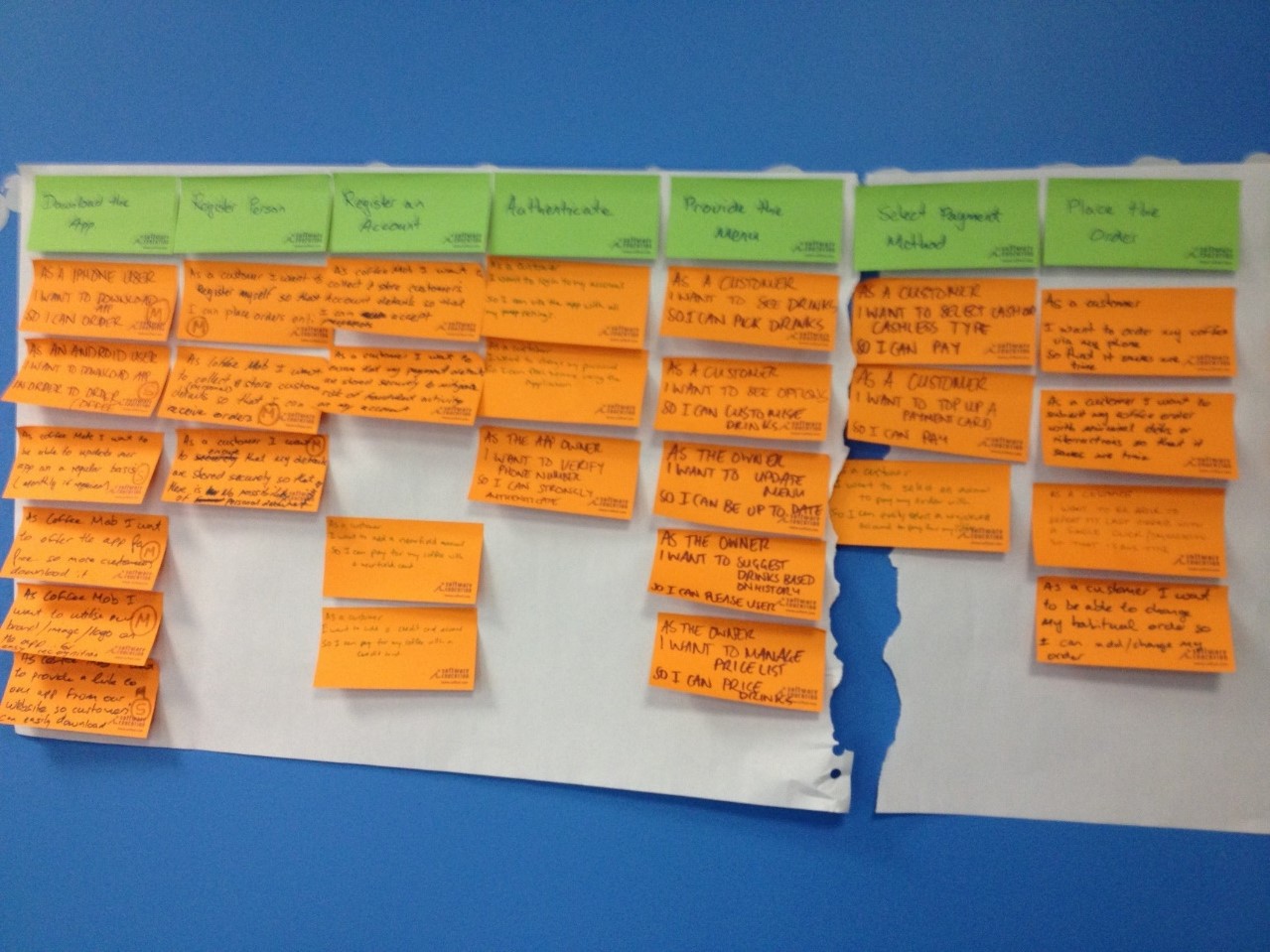

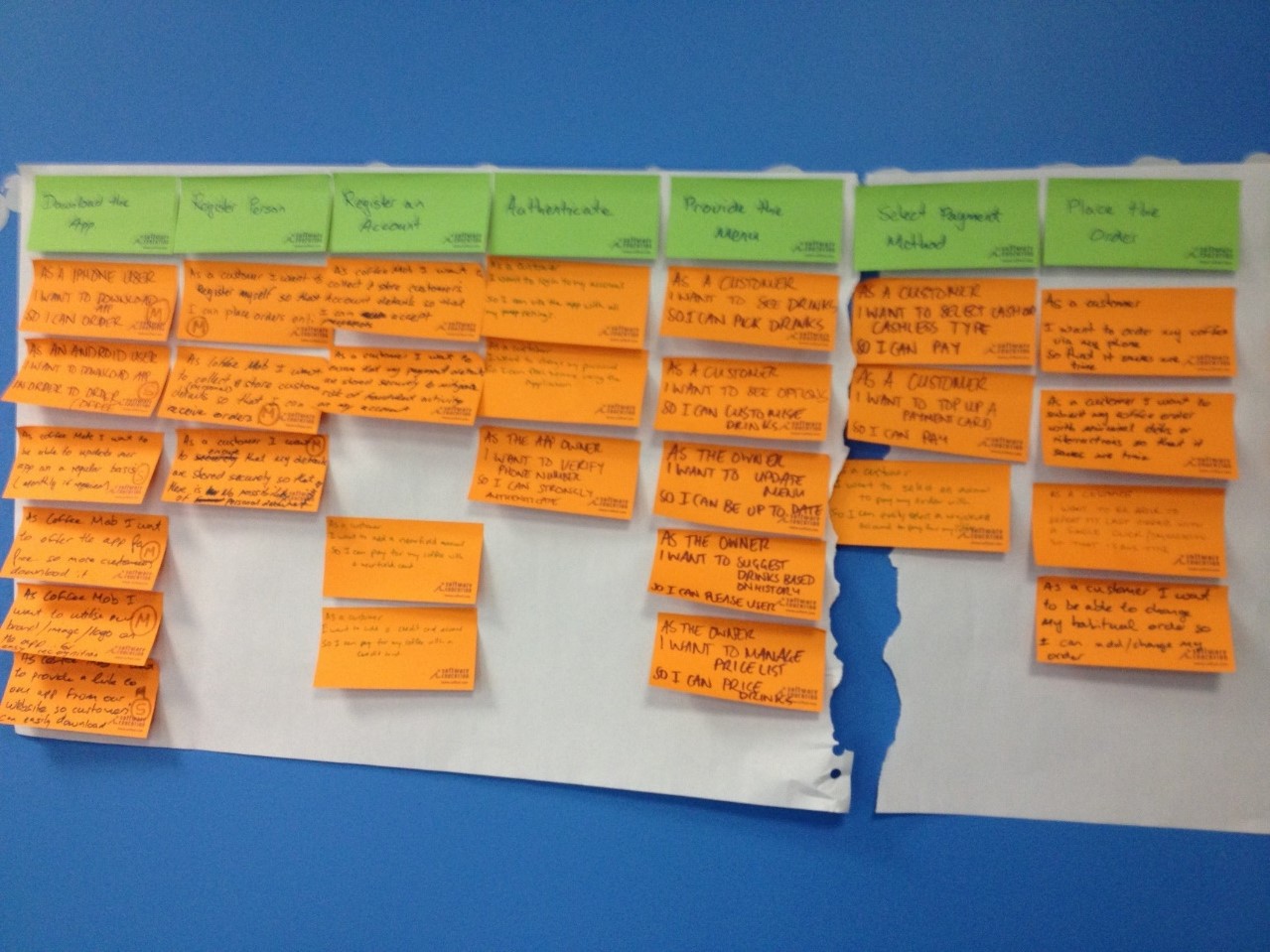

Image: An Example of a Story Map – Epics in green along the top

Epics can be put in sequential order along the top (if sequence is appropriate, which it normally is).

The next step in the Story Map is to populate the map with the User Stories that fall under the Epics. Each User Story is a small, discrete piece of functionality that has value to some user of the product and is a decomposition of the Epic above. The most common format for writing User Stories is “as a (role) I want (feature or capability) so that (business value to be delivered)” –

- As an internet banking customer I want to list my account balances so that I can understand my financial position.

- As an internet banking customer I want to list transactions on an account so that I can check the detail

The three elements are important – knowing who the story is for helps ensure we build a useable product, what the functionality is that is needed and the value which will be derived from having that functionality enable us to make good priority decisions.

Related Article: Technical User Stories: What, When, and How?

Priority based on business value is very important to defining User Stories. Knowing the value from a story enables us to make good decisions about the sequence of work – building the most important business value components first and getting feedback early rather than trying to build everything at once is inherent to Agile.

The User Stories are the orange cards in the image above.

Priority and Sequence Shown in the Map – identify the MVP

One of the benefits obtained by building a Story Map that shows the logical flow of activities (from Epic to Epic along the top) and the discrete elements of those Epics vertically down the page is the ability to clearly see both sequence and priority. Stories that are higher up on the map are more important (needed sooner) than those lower down.

The prioritisation and sequencing approach enable the discovery of the Minimum Viable Product (MVP) – those elements which need to be delivered to provide the opportunity to learn and adapt the product based on feedback from real customers/users. Finding the true essence of the product and getting that into the hands of real customers (probably just a small subset initially but enough to get feedback to validate the assumptions being made in the development of the product).

In a real-world internet banking example, the very first version of the product which was put in production had the ability to log in and to list balances and this version was used by the project team and a small group from within the bank. Having this “walking skeleton” built and put into production validated the architecture of the product, identified a number of unexpected challenges with the deployment process and gave the team feedback about their design philosophy which enabled them to make some significant changes when they were cheap and easy to do.

The Elements of a User Story

In his book, Mike Cohn says that a User Story has three C’s – the Card, the Conversation and the Confirmation. The Card is the initial User Story, written on an index card or PostIt note. This is deliberately short and devoid of detail. The intent is to defer the detail until later in the project, just ahead of when this piece will be delivered. The detail is established through the second C – Conversations. As the project progresses and elements are delivered there will be a number of conversations that result in clarity of understanding about what is actually needed to deliver the value identified in the User Story.

The final C is Confirmation – these are the Acceptance Criteria for the User story – the details which will enable the customers and the technical team to agree that “if this story meets these criteria it is done”. This is the detail which is all too often left out in bad Agile projects (“Tragile”). This detail needs to be agreed to, and it will contain whatever is needed to enable the delivery of this component of the product. The key difference between Agile and other approaches is when we produce this detail. In an Agile project this will be produced collaboratively with the customer representatives just ahead (a couple of hours to a couple of days) of when the piece will be built.

The most common format for these acceptance criteria is the structure of Acceptance Test Driven Development. Each user story will have a number of acceptance criteria and may also have other elements which will help ensure the right thing is built – these could include screen mockups, technical notes, models such as class diagrams and whatever the team needs to enable them to deliver the business value.

Examples (for the list account balances user story)

Given the customer has one credit account and one savings account

When they have logged in successfully

Then the two accounts will be listed in account number order (Account no, Name, Balance, Available Funds)

Given the customer has no accounts

When they have logged in successfully

Then a message indicating that there are no accounts to show will be displayed

Given the customer has twenty one accounts

When they have logged in successfully

Then the first twenty accounts will be listed in account number order

And a Next Page option will be enabled

Given the customer has twenty five accounts

And they have logged in successfully

And they are on the first page of the list

When they activate the Next Page button

Then the list will be cleared

And the list will be populated with the last five accounts

And the Previous Page button will be enabled

And the Next Page button will be enabled

Gojko Adzic’s book Specification By Example provides an excellent reference on how and when to produce acceptance criteria.

Ultimately the Acceptance Criteria will be proven through a set of test cases (ideally automated) which show that the product works as needed to deliver the business value.

Reduce Waste and Be Responsible

Again, the key to reducing waste and rework is to defer this detail until just ahead of when it is needed, rather than trying to clarify it all up front. Things will change over the life of the project and deferring the detail makes it cost-effective to adapt to this change.

However – taking this just-in-time approach is not an excuse for poor architecture or bad design. Early on in the product development it is important to set clear architectural guidelines, design principles and deal with what Philippe Kruchten calls the “Architecturally Significant Non-functional Requirements” – those aspects which will be extremely expensive and difficult to refactor later. Note however that we say “guidelines” and “principles” – don’t try to build the complete architecture up front, allow it to be emergent inside the boundaries of these clear guidelines.

Traceability in User Stories

Hopefully it is clear from this description that User Stories actually have a powerful traceability mechanism built into the design of the technique.

There is a cascading one to many relationship:

- A Role or Class of User derives value from one or many Epics

- One Epic could have many User Stories

- One User Story will eventually have many Acceptance Criteria

- One Acceptance Criterion will have multiple Test Cases which prove it is working as expected

This traceability is enacted through the “so that” component of the user story, which ensures that every piece which is implemented has a direct relationship to the business value to be derived from that component/capability.

Timing Makes the Difference

The key is the timing – User Stories are deliberately abstract early on in a project and will evolve over time on a just-in-time and just-enough basis. This is because Agile projects expect and anticipate change and respond to this change by adapting the product to the evolving needs. More User Stories will be added, some will be dropped and our understanding of many will change as time progresses. The reality of today’s business world is that change is inevitable, so trying to define the detail of all aspects of the upfront will result in lots of wasted effort and time as much of the work will need to be redone.

The Story Map is a fluid and changing tool – as stories are completed they are removed, new ones added and change is accepted as a normal part of the way we maximise the delivery of value to our stakeholders and the organisation for whom the product is being built.

The detailed Acceptance Criteria for any User Story will on be produced just ahead of when it will be delivered, maximizing the amount of work not done (one of the 12 principles of the Agile Manifesto)

One of the mistaken and dangerous myths of Agile is that “Agile projects have no documents” – the reality is Agile projects have the documentation that is needed to ensure value is delivered, and nothing more. The philosophy is to defer work until just ahead of when the output of that work is needed (a concept inherent in Lean thinking) and only do that work which is necessary to achieve the desired outcome (preventing waste from unnecessary effort and rework).

This is in stark contrast to Use Case thinking where the goal is to define in the various flows of the use case all the detail of the requirements up front. This approach will inevitably result in wasted effort as the use cases will have to be maintained and updated as the changing needs emerge. In agile we want to evolve the solution iteratively and incrementally as we learn based on feedback from real customers/users, not rework the documentation and requirements.

Could you use Use Cases instead of User Stories in an Agile project?

Theoretically Yes – you could indeed use Use Cases instead of User Stories to express the business needs. None of the Agile approaches are prescriptive about how you express the list of capabilities/features the product must contain (what Scrum calls the Product Backlog), however we see significant risks in trying to do so. Use Cases miss the mark on the “WHY”; they are not well suited to expressing the separate pieces of business value and supporting the iterative, incremental approach to developing the product – they tend to be monolithic and encourage an “all or nothing” way of thinking vs. an adaptive evolutionary style of learning and discovering the solution together through quick build and feedback loops.

Could you build Use Cases after developing an Agile solution to document the requirements after the fact?

Theoretically, yes . . . however with this approach you have missed out on a critical technique in User Stories to guide conversations towards maximising value and minimising extra work throughout the development process.

Risks and Dangers of Use Case Thinking in Agile Projects

- Compromised Innovation

- Use Cases bring on a lot of detail before getting feedback on a built product. This cognitively brings user mind-sets into a predefined interaction and solution, negating the potential for further innovation. The exploration and learning aspect is compromised and focus goes from solving a need to perfecting an already defined solution.

- Compromised Timelines:

- Too much detail before building compromises the benefits of time in the Agile approach. Spending time detailing out Use Cases is spending time on what and how when we be should focusing on the why. Defer the what and how until just ahead of when it is needed

- Compromised Value:

- Use Cases confuse the role of Acceptance Criteria in User Stories and agile. Many teams are using Use Cases as an alternative to creating Acceptance Criteria for their User Stories. Acceptance Criteria evolve in levels of detail as builds iterate and evolve and more is learned together through the agile process. This learning process is where the value lies as the needs are quite unknown before starting.

Conclusion

Many teams embarking on their Agile journeys are finding comfort in techniques used in the past for requirements definition, particularly Use Cases. Use Cases resemble user stories in more detail, and User Stories were developed as a condensed technique to alleviate the lack of WHY in Use Cases and to alleviate too much detail too soon when using an Agile approach.

We believe that User Stories and Acceptance Criteria are the techniques aligned to deliver the benefits of the Agile approach and Use Cases compromise and put the benefits of the Agile approach at risk.

Teams thinking about using Use Cases should strongly consider looking at the methods and evolutions of defining Acceptance Criteria (especially the model) with many scenarios and levels of detail that evolve as feedback through the iterative cycle and delivering increments of the product as it evolves. Keeping with user stories (Including story maps & epics) along with well defined and evolving acceptance criteria will meet the goal of leveraging the benefits of agile without putting timeline and value at risk.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

About the Authors

Shane Hastie

Shane Hastie

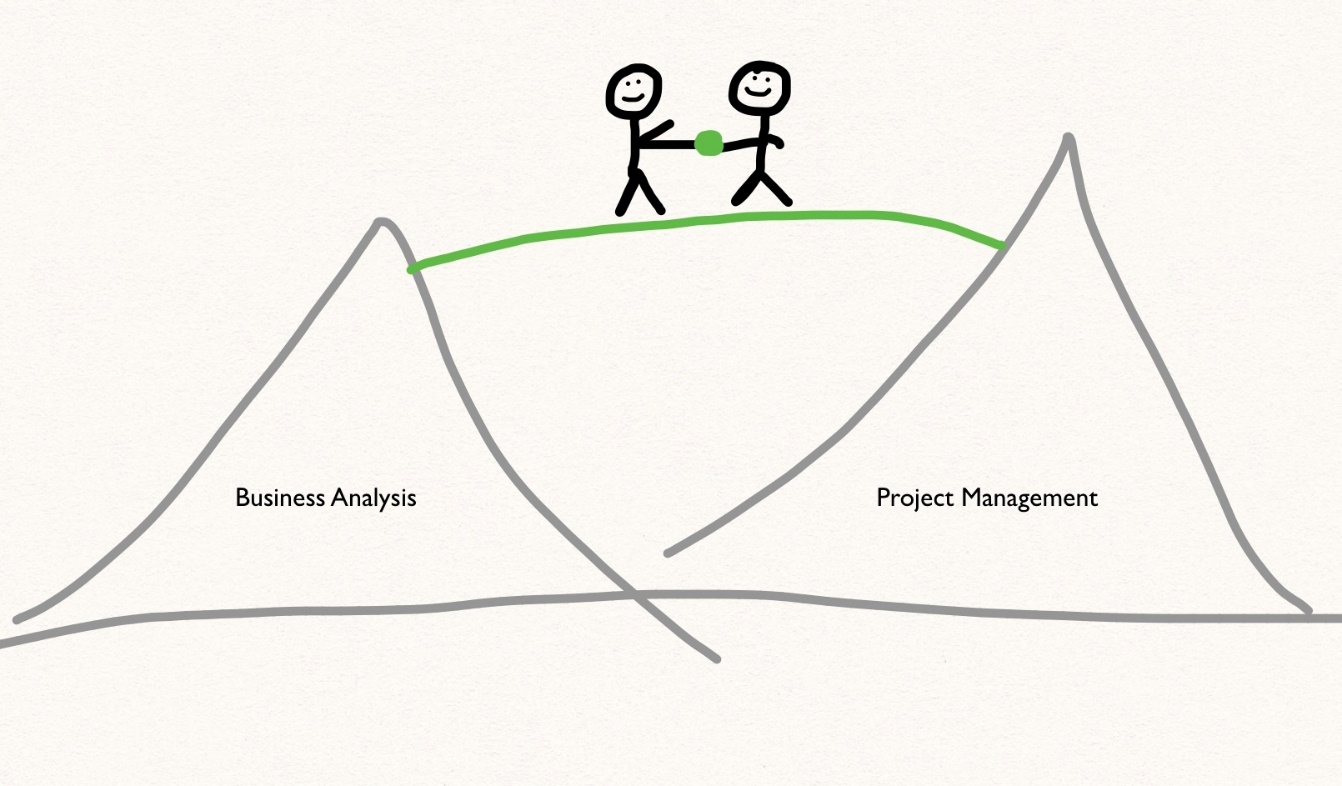

Shane is the Chief Knowledge Engineer and Agile Practice Lead for Software Education, a training and consulting organisation based in Australia and New Zealand, working all around the world.

Shane teaches courses and consults around business analysis and agile and is passionate about bringing the two communities together.

He is a member of the board of the Agile Alliance, and is the lead editor in the Process and Practices community on InfoQ.com

He can be reached at [email protected] and on twitter as @shanehastie

Angela Wick, CBAP, PMP

Angela Wick, CBAP, PMP

Ms. Wick is passionate about inspiring innovative BAs and is a leader in the business analysis field. Angela is a trainer of business analysis, project management and in bringing innovation and creativity to these roles. She enjoys working with traditional and agile teams, and especially in preparing teams for agile in their organization. She also consults with organizations in building BACoEs, BA practices, BA Career Models, and BA competencies. Angela is a lead contributor to the BABOK v3 and the IIBA Competency Model. Angela is also a monthly blogger on BaTimes.com

Angela can be reached at [email protected] and on twitter @WickAng

Both Shane and Angela are Core Team members for the IIBA team building version 3 of the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge (BABOK)

Shane Hastie

Shane Hastie Angela Wick, CBAP, PMP

Angela Wick, CBAP, PMP