Top Ten Tips for Tackling the CBAP Exam

It’s no surprise that the certification of business analysts is more sought after today than ever before. Worldwide the demand for qualified practitioners, and the ability for them to quickly demonstrate their capabilities in requirements management and development, continues to grow.

Growing almost as quickly is the number of people taking the Certified Business Analysis ProfessionalTM (CBAP®) exam. The 150-question exam is based on the International Institute of Business Analysts’ (IIBA®) Business Analysis Body of Knowledge® (BABOK®). This constantly evolving business analyst’s handbook reflects the most current, generally accepted business practices, and is one of the best references in preparing for the challenging multiple-choice exam.

So what does this mean to you? For those looking to take their careers forward, or to give themselves an advantage over the competition in the job market, the CBAP certification can mean an advanced career path, documented professional expertise and a positive impact on your organization. The exam is as challenging as the certification is valuable, but the time you take to prepare, from collecting and submitting your extensive application materials, is well worthwhile.

As with any standardized testing, there are literally hundreds of sources for information, tips and strategies. From that mountain of information, here are 10 widely recognized best practices for applying for, preparing for and taking the CBAP exam.

-

Take your time, part 1. Even applying to sit for the exam will take a significant amount of time. Most experts and CBAPs agree that you should give yourself at least eight hours total to complete the application. Yes, you read that right. Eight total hours. (When you read #2 below, you’ll understand why.)

Read each question and section carefully. Answer to the best of your ability and take the time to really focus on the application.

To further minimize omissions and errors – or the odds of having your application rejected – always use the IIBA-supplied templates, available with the application at http://www.theiiba.org/ under “get certified.”

-

Know the requirements and fees. To successfully apply for the exam, you must demonstrate your professional experience, specifically in indentifying business needs and determining the best solutions for business problems. The completed application must meet the following five requirements:

-

Work Experience: 7,500 hours of verifiable, hands-on business analysis work over the 10 years preceding your exam application.

-

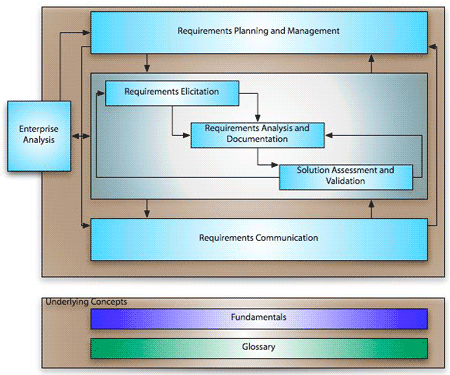

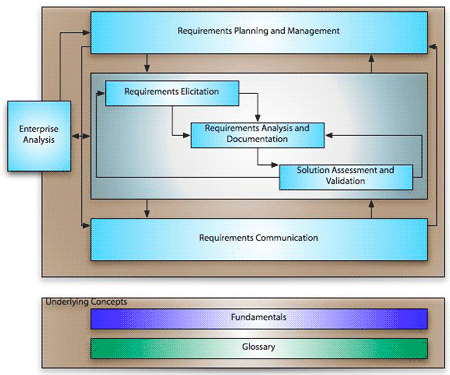

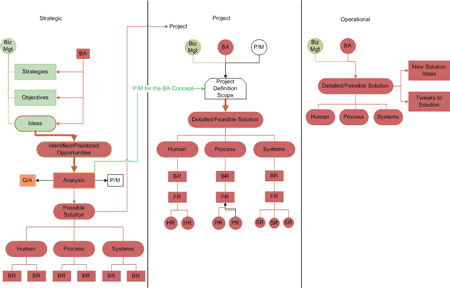

Knowledge Areas: Demonstrable experience and expertise in at least four of the six knowledge areas: Enterprise Analysis, Requirements Planning and Management, Requirements Elicitation, Requirements Analysis and Documentation, Requirements Communication, Solution Assessment and Validation, and Business Analysis Fundamentals.

-

Education: High school or equivalent

-

Professional Development: 21 hours of verifiable coursework in the past four years, directly related to business analysis.

-

References: Two references from a career manager, client (internal or external) or CBAP are required. These references must indicate that you are a suitable candidate for the CBAP® certification.

Next, consider applying for IIBA membership before applying for the exam. As you will see below, the fee schedule for the exam varies, depending on whether or not you are an IIBA member, with savings of $125 for members (exactly the amount of the application fee). Consider the idea that you will probably join IIBA after gaining your certification- so why not essentially apply for “free?”

Fees:

-

|

IIBA® membership fee: |

$95 USD

|

Paid annually. |

|

Application Fee |

$125 USD |

This fee pays for the processing and administration of your application. It is non-refundable.

|

|

Exam Fee – for IIBA®Members |

$325 USD |

The fee pays for the initial exam sitting and will NOT be reimbursed if you do not pass the exam.

|

|

Exam Fee – for non-IIBA® Members |

$450 USD |

The fee pays for the initial exam sitting and will NOT be reimbursed if you do not pass the exam. |

Please note: You can submit both the application and the exam fees with your application. If your application is declined, you will be reimbursed the exam fee.

-

Know your study style. Once you’ve applied, you can then expect to devote a substantial amount of your time and attention to preparation. Experts estimate total “ideal” study time at anywhere from six weeks to six months.

Before jumping in, have a clear understanding of how you learn and retain information. This point can’t be stressed enough. Quite simply, what many people forget, especially if they haven’t taken an examination in some time, is that not every study method works for every person.

For example, you may be a visual learner, or perhaps you remember spoken words more readily. Do you do better taking classes and interacting with others or working through study guides on your own? Tailoring your preparation to your style will save you hours – if not days – of frustration and increase your confidence on exam day.

-

Know your resources. With the vast number of available study methods and resources, narrow your choices by creating a list of study resources and be very selective, keeping in mind your personal style (#3 above). CBAP study guides featuring practice examinations are available, as well as business analysis courses to help you prepare for the exam, maintain your certification, and build upon your existing skills.

Regardless of the preparation regimen you ultimately choose, it’s wise to contact your local IIBA chapter. Many chapters offer study groups, or you can leverage the knowledge of peers who have already achieved their CBAP® certification.

-

Get a flash of brilliance. Even in this age of palm-sized computers and high-speed mobile Internet, one popular preparation method is decidedly “low-tech.” Many CBAPs laud flash cards as study tools for exam terms and definitions of each knowledge area – so much so that the study technique is actually featured in many preparation courses. Even if you’ve chosen not to take a formal course, consider making some flash cards for yourself. They’re an easy, efficient way to study anywhere.

-

Demonstrate intimate knowledge. Memorizing terms and knowing the BABOK is just one part of passing the CBAP exam. Since the exam uses situational scenarios throughout, understanding of language, usage and context for all six knowledge areas is also very important. Success depends on your ability to align your business analysis experience with the exam questions.

-

Know your activities. Next, memorize the tasks and activities within each knowledge area. If you aren’t already, become familiar with the input and output of each activity across all knowledge areas. Knowing what you’re supposed to get out of a solution will increase your confidence as you work your way through the examination.

You can get a feel for activities by creating your own small models for each knowledge area or by using the models included in many of the available classes or guides. -

Know your modeling. Usage, process, flow, data and behavior models are all areas tested on the exam. Since the exam focuses on practical, situation-based questions, it’s very important to devote significant time to practicing modeling and more importantly, becoming familiar with when to apply each.

-

Practice, Practice, Practice. All the studying in the world is for naught if you’re surprised when you sit down for the actual exam. Whatever your preparation method, be sure to develop a plan for practicing with CBAP-format questions or full-blown practice examinations. Set aside three hours, find a quiet spot, and work your way through. After a few practice exams, and knowing exactly what to expect, the real one won’t seem so intimidating.

-

Take your time, part 2. The night before the exam, don’t try to cram or re-read the BABOK. Just get a good night’s rest – it is a three-hour-long, taxing test, and being focused and alert is the best favor you can do for yourself.

On the day of the exam, dress comfortably and bring paper and pencil to work out your answers. Most testing facilities provide these, but it never hurts to be prepared.

If you’ve memorized items, you are allowed to write on the exam booklet, so get them written down before you begin – it will give you one less thing to think about.

Finally, put everything you’ve learned to use and pace yourself. You’re not scored on how quickly you complete the exam and rushing leads to costly mistakes. If you do not pass the exam, you must wait three months before you are allowed to re-take it.

Scoring the exam takes up to 30 days and results will include knowledge area breakdowns for those who have not passed.

Without proper preparation, the CBAP examination can be intimidating. However, if you solidify your skills and knowledge and take advantage of your experience as a Business Analysis professional, you’ll have your certification sooner than you think.

Good luck.

Glenn R. Brûlé, Executive Director, Client Solutions, ESI International, is author of CBAP Exam: Practice Test and Study Guide, First Edition. He has more than 18 years experience in many facets of business, including project management, business analysis, software design and facilitation. At ESI International, he is responsible for supporting a global team of business consultants working with Fortune 1000 organizations. These engagements focus on understanding, diagnosing and providing workable business solutions to complex problems across various industries. Glenn is a Member of the Board of Directors and Vice President of Chapters of the International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA). For more information, visit http://www.esi-intl.com/.