Do You Measure Up?

If there’s one aspect of business analysis that bears greater emphasis and attention, it’s measurement. Quantification and measurement are the business analyst’s sure-fire means to show his or her value to the organization as well as the value of the profession. However, BAs often aren’t as diligent or knowledgeable as they should be about measurements.

One of the top requirements management and development (RMD) trends to be on the lookout for this year is greater balance between the BA’s soft skills and technical proficiency with graphical modeling, cost estimates, risk analysis and other measurements. The important thing to remember is that measurements don’t have to be complicated; in many cases a spreadsheet and a calculator will suffice.

Now, let’s look at how to provide measurement procedures and techniques to gauge the value of business analysis as the organization moves from the as-is to the to-be state.

Start With a Three-Pronged Approach

Often the reason BAs don’t adequately measure is because of uncertainty or perceived complexity of measurement requirements. When thinking about measurement, it’s helpful to understand the delineation of the three key areas of the BA’s focus, each of which will demonstrate a close linkage to the others:

- Organizational measurement

- Process measurement

- People/performance/skills measurement.

Organizational measurement looks at business performance to determine whether the BA’s contribution had an impact on success metrics. Measurement is one of the key techniques for charting the course for deconstructing and reconstituting the organization to verify strategic goals are being met.

Consider another of this year’s top RMD trends-the key role RMD will play in organizations regaining market share. The means by which market share can be increased include:

- reaching a new demographic

- putting a new spin on an existing product

- adding, removing or improving on existing services

- creating a new efficiency.

At their foundation these goals and objectives have a corresponding financial value which the BA can measure.

At the process level, using songs available from iTunes as a hypothetical example helps illustrate how the BA’s measurement is critical to creating greater efficiencies. Consider, for instance, that the organization states a business need to increase growth by 10 percent. Raising the price of a song from $.99 to $1.29 increases profitability, but doesn’t increase market share. Looking at the variables that address market share, the BA would examine key performance indicators-song sample time, number of clicks it takes to buy a song, promotion and advertising-and measure the impact they have.

Measurement can also be used to determine if an organization has the right people in place with the right skills by identifying areas of competencies and gaps. For example, a business analyst may be a highly effective facilitator of requirements management, but poor at modeling techniques. This disparity in skills sets will obviously impact project efficiencies.

Measuring From the Top Down

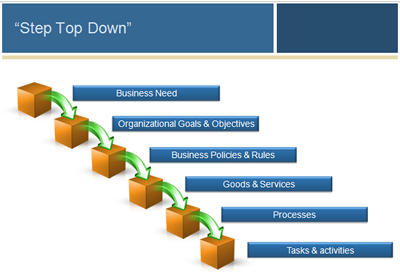

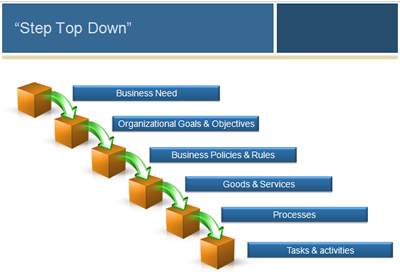

Determining measurements for each of these three areas fits within the context of the following “step top down” chart which depicts the focus areas of a project, and also serves as a guide of signposts indicating where measurement, and the opportunity for creating greater efficiencies, should take place.

Take, for example, an organization that determines a business need to become the exclusive provider of Class A widgets. How that will be accomplished is established in goals and objectives, which require creating new efficiencies, whether by developing a new product or service, reducing production time, or increasing production levels, among other options.

The organization’s business policies and rules dictate the manner in which the organization conducts itself, and their impact provides distinct outcomes that can be measured. This measurement provides the opportunity to evaluate whether a rule or policy should be changed.

Measurement at the goods and services level assures that the organization is selling the right products and providing the right support services. This is where measurement can determine questions such as whether enough of a product is being sold or if the product being sold is meeting market demand.

Processes help accomplish the delivery of the organization’s goods and services, and measuring their outcomes are critical to determining whether greater efficiencies can be created.

Tasks and activities are the individual components that are necessary to support the process. Their performance and outcomes can be measured so that changes such as reducing or consolidating steps of a task can shorten delivery or output times.

A favorite exercise that illustrates the concept of measuring throughout project levels is applying business analysis skills and techniques to baking a cake. Starting with a business need to produce a homemade chocolate fudge cake, consider the requirements that go into the final product. What ingredients will be used, where will they be sourced, and where and in what kind of oven will the cake be baked? Where can improvements be made in how the cake is created and in the quality of the final product? Creating greater efficiencies in the various steps to baking a cake requires good measurements that can demonstrate what the BA’s skills contributed to the mix.

The Quick and Dirty Checklist of Measurement Techniques

In A Guide to the Business Analysis Book of Knowledge® (BABOK®), Chapter 9 provides a high level overview of BA techniques, which include useful methods for measurements that BAs should utilize throughout a project or initiative. To avoid getting bogged down and overwhelmed with measurements, one key suggestion to remember is to conduct measurement at a frequency that is acceptable or in alignment with the project complexity. With that in mind, here are the essential BABOK techniques to refer to when gathering measurements:

9.1 Acceptance and Evaluation Criteria

These are the minimal set of requirements necessary for the implementation of a solution and the set of requirements used to choose between multiple potential solutions.

9.2 Benchmarking

Benchmarking measures the results of one organization’s practices against another’s, and compares current outcomes with previous outcomes. Anything pertaining to the organization, processes or people can be benchmarked.

9.8 Decision Analysis

Decision analysis enables the evaluation of different options and is particularly helpful under uncertain circumstances. The BABOK describes particular tools to use to analyze outcomes, uncertainty and tradeoffs.

9.10 Estimation

The eight estimation techniques in the BABOK traditionally have been in the project manager’s toolkit, but they can be applied to business analysis as well. They can help develop a better understanding of the potential costs and effort that an initiative will incur.

9.16 Metrics and Key Performance Indicators

A metric is a quantifiable measure of progress and can be used to measure a Key Performance Indicator, an indicator that shows progress toward a strategic goal or objective. As previously stated, less complexity is preferable with measurement, so whenever possible, select only three to five indicators for metric reporting.

Measuring Will Show the BA’s Value

For BAs, it’s critical to show quantification of the input they have provided and be able to definitively state that business analysis resulted in a five percent increase in profitability or a 10 percent time saving in a process or any other relevant metric of improvement. Though many organizations struggle with what should be measured, these techniques and methods will help demonstrate what the business analyst has contributed. Measurement, after all, is as straightforward as baking a cake.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

Glenn R. Brûlé, CBAP, CSM, Executive Director of Global Client Solutions, ESI International, has more than 20 years of business analysis experience. He works directly with clients to build and mature their BA capabilities, drawing from the broad range of ESI learning resources. A recognized expert in the creation and maturity of BA Centers of Excellence, he has helped clients in industry and government agencies across the world. For more information visit http://www.esi-intl.com/.

As business analysts we can agree that benchmarking is important, but from that point on we’re likely to find the conversation diverges. Differences abound in approaches of how and what to benchmark in order to prove value. Organizations become overzealous in what they want to benchmark and scorecard in their drive to create greater efficiencies. However, a key component for developing and monitoring successful metrics is ensuring that they are in alignment with the maturity of an organization. Knowing when to say when can enable less mature organizations to develop metrics that are both useful and appropriate at the developmental level.

As business analysts we can agree that benchmarking is important, but from that point on we’re likely to find the conversation diverges. Differences abound in approaches of how and what to benchmark in order to prove value. Organizations become overzealous in what they want to benchmark and scorecard in their drive to create greater efficiencies. However, a key component for developing and monitoring successful metrics is ensuring that they are in alignment with the maturity of an organization. Knowing when to say when can enable less mature organizations to develop metrics that are both useful and appropriate at the developmental level.

Most organizations today are performing business analysis at a community of practice level. They have recognized the need to develop the skill sets of their BA resources, and may have even gone as far as doing an assessment and evaluation of the level of competency of their BA group. As such they were able to identify any gaps that might exist in both performance and overall competencies and job descriptions. Other organizations have also begun to put into place a solution development lifecycle and are likely to be in the process of either redefining or developing one. A common question that comes up is this; what do we develop first, the people or the processes? My response is go with the egg, eventually the chicken will come! The processes need to define what needs to be done, and how it will be done, in the context of an SDLC. Job descriptions must define the ability, skill and knowledge necessary to perform the tasks and activities defined in the SDLC. The solution development lifecycle and job descriptions/career paths and competencies must be closely interrelated. They may begin to demonstrate an alignment with the PMO.

Most organizations today are performing business analysis at a community of practice level. They have recognized the need to develop the skill sets of their BA resources, and may have even gone as far as doing an assessment and evaluation of the level of competency of their BA group. As such they were able to identify any gaps that might exist in both performance and overall competencies and job descriptions. Other organizations have also begun to put into place a solution development lifecycle and are likely to be in the process of either redefining or developing one. A common question that comes up is this; what do we develop first, the people or the processes? My response is go with the egg, eventually the chicken will come! The processes need to define what needs to be done, and how it will be done, in the context of an SDLC. Job descriptions must define the ability, skill and knowledge necessary to perform the tasks and activities defined in the SDLC. The solution development lifecycle and job descriptions/career paths and competencies must be closely interrelated. They may begin to demonstrate an alignment with the PMO. There is no doubt in my mind that many organizations have demonstrated in some capacity their level of maturity given a specific area with the guiding principles in level of maturity. They may include some of or all of the following items, but in order to move from one degree of maturity to another demonstration of the following with consistency over a period of time is necessary. A direct reporting structure to either the PMO or the CIO may be in place a Director of the BAB is likely to be the leader of the BAs and as such is making strides to present his team as a distinct business unit. The team is clearly a distinct pool of resources. From a services perspective they are beginning to show signs of credibility amongst the business unit leaders as a result of consistent performance excellence. Business Unit Leaders are seeking out the team to provide assistance when needed, and the recognition of moving from a tactical to strategic role is beginning to form.

There is no doubt in my mind that many organizations have demonstrated in some capacity their level of maturity given a specific area with the guiding principles in level of maturity. They may include some of or all of the following items, but in order to move from one degree of maturity to another demonstration of the following with consistency over a period of time is necessary. A direct reporting structure to either the PMO or the CIO may be in place a Director of the BAB is likely to be the leader of the BAs and as such is making strides to present his team as a distinct business unit. The team is clearly a distinct pool of resources. From a services perspective they are beginning to show signs of credibility amongst the business unit leaders as a result of consistent performance excellence. Business Unit Leaders are seeking out the team to provide assistance when needed, and the recognition of moving from a tactical to strategic role is beginning to form. You’ve developed partnerships with the executive. Your team is sought after as the change leaders of the organization. You are clearly recognized as a customer service solution. You and your team have demonstrated your discipline both tactically and strategically. Most importantly, you have clearly defined the art of Enterprise Analysis (EA) and demonstrated your ability in the five areas of EA including, Business Architecture, Information Architecture, Application Architecture, Technology Architecture, and Security Architecture. Your team is providing and sponsoring studies to participate in overall corporate advanced and BPI & KPI’s and overall business effectiveness. Your continuous assessment and evaluation of performance on internal process and customer satisfaction has become commonplace.

You’ve developed partnerships with the executive. Your team is sought after as the change leaders of the organization. You are clearly recognized as a customer service solution. You and your team have demonstrated your discipline both tactically and strategically. Most importantly, you have clearly defined the art of Enterprise Analysis (EA) and demonstrated your ability in the five areas of EA including, Business Architecture, Information Architecture, Application Architecture, Technology Architecture, and Security Architecture. Your team is providing and sponsoring studies to participate in overall corporate advanced and BPI & KPI’s and overall business effectiveness. Your continuous assessment and evaluation of performance on internal process and customer satisfaction has become commonplace.