I See What You Mean… Leveraging Transparency!

One of the core tenets of the agile methods is transparency. I’ve been doing agile for nearly 10 years and this is one of the tenets that I find myself understanding and appreciating more and more as I gain experience. It’s the tenet that keeps on giving.

Let’s generally define it first. What is transparency?

I think it comes down to exposing the inner workings of a software project for all to see. To have high comfort and honesty in sharing project “state” with team members, stakeholders, and company leadership. Included is the ability to engage in honest, open dialogue surrounding any issues leading towards requisite project adjustments.

How Do You Foster Transparency?

The first part of it is simply sharing “state”. For example, I view early reviews of requirements documentation as being a transparent moment-particularly if they’re incomplete. In Scrum, each iteration ends with a Sprint Review where the team demonstrates the code and artifacts they’ve created during the sprint (iteration). There’s no simulation here. Instead the emphasis is always on working code and relevant models completed in the sprint.

So, stakeholders can see and react to exactly what we’ve done so far.

Another Scrum practice is the daily standup meeting or daily scrum. Here the team gets together and shares the progress and challenges they’re facing in the current sprint. If they’re behind, it’s evident and corrective action discussion occurs in real-time. If they’re ahead, then discussion surrounds pulling more work into the sprint. Either way, you understand the ebb and flow of the work on a daily basis. Scrum teams welcome visitors to the daily scrum as a means of transparent status gathering.

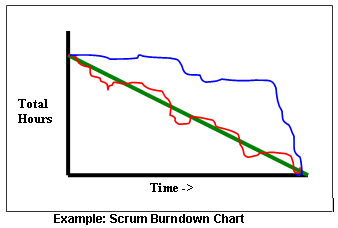

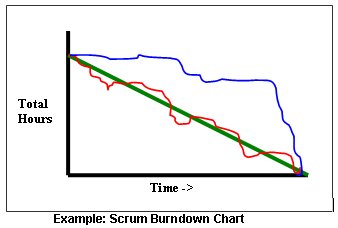

A final Scrum practice that fosters transparency is the notion of a Burndown Chart. You can see an example below. In this case we’re burning down cumulative work that the team planned over the course of a sprint or iteration. The green line is the perfect trending line. Each day, the team gets credit for completed task work and “burns down” the chart hours appropriately. You see in the example that the blue line gives an entirely different view of the team’s progress than does the red. It opens the door for questions from the team and stakeholders – leading towards comfort or adjustments.

What Does Transparency Do?

It removes wishful thinking on the part of the team and stakeholders. Instead of thinking that the project is about 40% complete, a transparent view is that 32 of our 96 features are absolutely complete, with 12 being works in progress. That implies that we are exactly 33% complete. And at this rate, it will take us twice the current progress interval to get the work completed if the features are roughly the same in size and complexity.

It keeps us grounded in the now – not worrying too much about the future. Instead, how are we trending towards our next deliverable? And, if not so well, how do we take corrective action now to improve our potential for delivery?

It creates conversations surrounding reality and movement towards your goals. I literally love it when a stakeholder stops me in the hall and ask about our current burndown chart for a specific Scrum team…

“Bob, I’ve noticed that It’s day 4 of a 10 day sprint and the burndown chart seems to be flat. That implies that we’re not making our expected progress. Yes, it does, I say. Well what can we do about it? I offer a couple of thoughts. First, we don’t know if we have an issue yet. The team may simply be working on things that haven’t been integrated yet, and we’re “on track”. So we ought to engage the team and ask them how things stand – perhaps in tomorrows stand-up?”

If we are tracking worse than expected, then I’ll engage the stakeholder right then with trade-off options. I’ll direct them away from quality trade-offs and focus on scope. I’ll usually ask questions surrounding jettisoning scope while still being able to meet our sprint goals. All the while, trying to make the problem and the solution ours instead of mine.

So What Does this Mean for the BA?

Leverage transparency to your advantage. Open up your work incrementally, early and often, for review and feedback. Don’t get defensive when you hear things that you don’t quite agree with. Take the feedback, internalize it, and take appropriate action within your work’s flow.

Let everyone know how you’re progressing towards project goals. What are your high priority focus points and conversely, the low priority counterpoints. Let everyone know how your work aligns with the schedule. Don’t hide anything and don’t be optimistic or pessimistic. Just relay where you honestly stand and the potential for adjustments.

I encourage everyone to simply try transparency. It’s the gift that keeps on giving!

Don’t forget to leave your comments below