Equipping and Empowering the Modern BA

The principles of agile development were proven before agile – as a defined approach – became vogue. Agile principles were being practiced to varying degrees in most organizations as a natural reaction to the issues surrounding a rigid waterfall approach.

Every individual task on a software project carries some degree of risk. There are many sources of these risks – some third party component may not function as advertised, some module your work is dependent on may not be available on time, inputs to the task were ambiguous and you made an incorrect assumption when ‘filling in the blanks’, the list is endless. All these risks in the individual tasks contribute to the overall project risk and, quite simply, risk isn’t retired until the task is done. Putting it another way, the risk associated with building something is really only retired when the thing is built. That’s the principle behind iterative and incremental development.

So instead of leaving the first unveiling of a new or enhanced application until toward the end of the project, break it down so that pieces (functional pieces) can be built incrementally. While this doesn’t always mean the portions are complete and shippable, stakeholders can see them working and try them out. This offers several advantages: it retires risk, as mentioned before. It often also exposes other hidden risks. These risks will surface at some point, and the earlier the better. Exposing hidden risk and retiring risk early makes the estimating process more accurate. This increases the probability of delivering applications of value that address the business needs in terms of capability as well as budget and schedule needs.

While agile is becoming main stream on small and mid-sized projects, challenges do exist elsewhere such as how to manage this approach on larger projects and in distributed development. Another challenge for many is how to apply a requirements lifecycle to agile projects. Many agile principles such as “just enough and no more”, to “begin development before all requirements are complete”, to “test first”, can be counter-intuitive. Also, what about non-functional requirements? What about testing independence? How can we cost something if we don’t know what the requirements are?

This article attempts to describe some ways to handle these challenges. It is based on an example of real, ongoing, and very successful product development that uses agile with a globally distributed team. It describes one set of techniques that is known to work.

Process Overview

There are many “flavors” of agile, but at a high level they all essentially adhere to the following basic principles:

|

PRINCIPLE

|

DESCRIPTION

|

|

Iterative

|

Both Requirements and Software are developed in small iterations

|

|

Evolutionary

|

Incremental evolution of requirements and software

Just Enough “requirements details”

|

|

Time-Boxed

|

Fixed duration for requirements and software build Iterations

|

|

Customer Driven

|

We actively engage our customers in feature prioritization

We embrace change to requirements/software as we build them

|

|

Adaptive Planning

|

We expect planning to be wrong

|

Requirements details as well as macro level scope are expected to change as we progress through our release.

For the purposes of this article, our example uses a Scrum-based Agile process1. In this approach the iterations (sprints) are two weeks in duration. A sprint is a complete development cycle where the goal is to have built some demonstrable portion of the end application. It should be noted that while the initial sprints do involve building a portion of the application, often this is infrastructure-level software that’s needed to support features to be developed in later sprints. This means there may not be much for stakeholders to “see”.

Each organization needs to determine the sprint duration that’s optimal for them. It needs to be long enough to actually build something, but not long enough for people to become defocused and go off track (thereby wasting time and effort). We found two weeks to be optimal for our environment.

Key during the first part of the process is to determine and agree on project scope, also known as the “release backlog”. Determining the release backlog itself could be a series of sprints where the product owner and other stakeholders iterate through determining relative priority or value of features along with high level costing of these features to arrive at a release backlog.

At the other end of the project, development of new code doesn’t extend to the last day of the last sprint. We typically reserve the last few sprints, depending on the magnitude of the release, for stabilization. In other words, in the last few sprints only bug fixing is done, and no net new features are developed. This tends to go against the agile purists approach to software development as each sprint should, in theory, develop production ready code. However, to truly achieve that requires significant testing and build automation that most organizations don’t have in place. This is always a good goal to strive towards, but don’t expect to achieve this right away.

Requirements Definition in this Process

There are several ways you could perform requirements definition in an agile process, but again our goal is to introduce an example that’s been tried and is known to work. This example begins with the assumption that you already have a good sense of the “business need”, either inherently in the case of a small and cohesive group, or by having modeled the business processes and communicating in a way that all understand. So we begin at the level of defining requirements for the application.

Requirements at the Beginning

Begin with a high-level list of features. Each feature is prioritized by Product Management or Business Analysts (depending on your organization). These features are typically then decomposed to further elaborate and provide detail and are organized by folder groupings and by type. If needed to better communicate you should create low-fidelity mockups or sketches of user interfaces (or portions) and even high-level Use Cases or abstract scenarios to express user goals. We sometimes do these and sometimes not, depending on the nature of what’s being expressed plus considering the audience we’re communicating with. For example, if we’re communicating a fairly simple concept (how to select a flight) and our audience is familiar with the problem space (they’ve built flight reservation applications before) then clear textual statements may be “just enough” to meet our goals at this stage. These goals are to establish rough estimates (variance of 50-100%) and based on these and the priorities, to agree on the initial scope of the release (what features are in and which are out).

Once reviewed, this list of features becomes the release backlog. The features are then assigned to the first several sprints based on priority and development considerations.

Click image for larger view

Example High Level Features with Properties

Requirements During the Sprint

With respect to the requirements, the principle of “just enough” is paramount. If the need has been expressed to a degree adequate enough to communicate and have it built as intended, then you’re done. Going further provides no additional value. This means you’ll have a varying level of detail for the requirements across the breadth of the product. For some parts of the product a high-medium level of detail may be “just enough”, while for other more complex areas a very fine level of detail may be needed.

In each sprint there are tasks of every discipline taking place. Requirements, design, coding, integration, and testing tasks are all being performed concurrently for different aspects of the system. The requirements being defined in one sprint will drive design and coding in a subsequent sprint. The net effect is that all these disciplines are active in every sprint of the lifecycle, but the relative emphasis changes depending on what stage you’re at in the project. For example, requirements tasks are being performed in all sprints, but they are emphasized more in the earlier sprints.

In each sprint, the high level features are elaborated into greater levels of detail. This more detailed expression of the requirements usually begins with usage scenarios/stories and/or visuals and it’s expressed in the form of a model. The models can emphasize user interface, use cases, scenarios, business rules, and combinations of these, depending upon the nature of what is being expressed. Sometimes these are created collaboratively but more often in our experience, one person creates an initial version and then holds a review with others for feedback. In our case it is typically the product managers and/or business analysts who create these models and usually between one to three reviews are held with the developers, testers and other stake holders. The review serves multiple purposes including:

- To facilitate knowledge transfer to all stakeholders including architects, UE designers, developers, testers, and executive sponsors on what is needed

- To allow the architects, UE Designers and developers to assess feasibility

- To determine if there is sufficient detail in the requirements to allow development to proceed

With appropriate technology, tests are automatically generated from the requirements producing tests that are 100% consistent with the requirements and enable the immediate testing of code developed during sprints.

Continuous and Adaptive Planning

With this approach planning is continuous and adaptive throughout the lifecycle allowing resources to be redirected depending on new discoveries that come to light during each sprint. This ability to course correct in mid-flight is what gives projects their “agility”. At the end of each sprint we take stock of what was achieved during the sprint and record progress actuals. The work of the next sprint is adjusted as necessary based on this but also based on testing results, feedback from reviews of that sprint’s build, any new risks or issues that surfaced or others that were retired, and also any external changes in business conditions. Estimates and priorities are adjusted accordingly and any changes to release scope and sprint plans are made. In general we try not to make major mid-flight corrections during a sprint, which is one of the reasons why we like two week sprints. If sprints were, say, four weeks then we would lose agility. Also a two week sprint is easier and more accurate to estimate than a four week one.

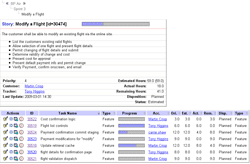

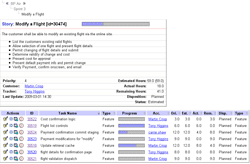

Click image for larger view

Example Story with Tasks, and Estimates

With respect to the requirements, for those features assigned to the sprint along with any high-level requirements models, development creates high-level goals for the particular feature and estimates them. The goals express what aspects of the feature they will attempt to build during that sprint, recognizing that one sprint is often not enough time to implement an entire feature. The feature and its high-level goals become the content of the “story”. Once the story is defined the developer then details and estimates the tasks to be done for that story over the next two weeks (sprint) and proceeds with development, tracking daily progress against these tasks in an agile project management tool, and covering issues in the daily scrum.

What about the Non-functional Requirements?

The various agile approaches have evolved several techniques to express system functionality. These are things like user stories, use cases, or usage scenarios, that represent “observable system behaviors and artifacts that deliver value to users” like screens, reports, rules, etc. These functional requirements express “what” the system is to do. Examples of this could be things like “generate a stock-level report”, “make a car reservation”, “register for a webinar”, or “withdraw cash”.

Associated with the functionality of a system are its “qualities”. These express “how well” the system is supposed to do what it does – how fast, how reliably, how usable, and so on. Sometimes these non-functional requirements are associated with certain functional requirements and other times they apply to whole portions of the system or the entire system. So how do these very important requirements get accounted for in our agile process?

They are expressed at the high-level in the form of textual statements. For example: “Any booking transaction shall be able to be completed by a user (as defined in section a) in less than three minutes, 95% of the time”.

As functional requirements are decomposed and derived any associated non-functional requirements should similarly be decomposed, derived, and associated to lower levels. For example the above performance requirement is associated with all the “booking transaction” functional requirements (book a car, book a flight, book a hotel). If the functional requirements are decomposed into the lower level requirements “select a car”, “choose rental options”, and “check-out”, then the non-functional requirement may similarly be decomposed into requirements for selecting a car in less than 30 seconds, choosing options in less than one minute, and checking out in less than 1.5 minutes.

During review sessions the functional requirements take center stage. However, during these reviews any non-functional requirements that are relevant need to be presented and reviewed as well. Traceability is usually relied on to identify them. Any non-functional requirements relevant to the functional requirements of the story need to be expressed as part of the story, so the developer can take these into account during development.

QA needs to create tests to validate all requirements, including the non-functional requirements. Sometimes before a feature has been completely implemented, non-functional requirements can be partially tested or tested for trending, but usually cannot be completely tested until the feature is completely implemented (which can take several sprints).

What about Testing?

The high degree of concurrency in agile processes means that testing is performed in every sprint of the lifecycle. This can be a considerable change from traditional approaches and offers several benefits. First, it tends to foster a much more collaborative environment as the testers are involved early. It also, of course, means that items which wouldn’t have been caught until later in the lifecycle are caught early when they can be fixed much more cheaply.

In agile, Product Owners play a very big role in the testing process and they do so throughout the development lifecycle. Whereas many traditional approaches often rely on requirements specifications as “proxies” of the product owners, agile places much more reliance directly on the product owner effectively bypassing many issues that can arise from imperfect specifications. In addition to the product owners, developers also test. Test-driven development is a prominent technique used by developers in agile approaches where tests are written up-front and serve to guide the application coding as well as performing automated testing, which helps with code stability. To augment test driven development, which is primarily focused at the code level testing done by developers, new technologies that can auto-generate functional tests from functional requirements enable a QA team to conduct functional testing based on test cases that are not “out of sync” with the requirements specification. This enables the QA team to conduct testing on a continuous basis, since executable code and test cases are available throughout the lifecycle. In our example, all three are employed – product owner, development staff, and independent QA – on a continuous basis.

The requirements that we develop in our example are a decomposition of high-level text statements augmented by more detailed requirements models that give a rich expression of what is to be built. Requirements reviews are based on simulations of these models and they are incredibly valuable for a number of reasons. First, just as agile provides huge benefit by producing working software each sprint that stakeholders can see and interact with, simulation lets stakeholders see and interact with ‘virtual’ working software even more frequently. Second, people often create prototypes today trying to do much the same thing. The difference with prototypes, however, is that simulation engines built for requirements definition are based on use cases or scenarios and, therefore, guide the stakeholders in how one will actually use the future application, providing structure and purpose to the requirements review sessions. Prototypes, including simple interactive user interface mock-ups, on the other hand, are simply partial systems that ‘exist’ and provide no guidance as to how they are intended to be used. Stakeholders have to try to discover this on their own and never know if they’re correct or if something has been missed. It is important to note that the principle of “just enough” still applies when producing these models. We rely on the requirements review sessions held with designers/developers to determine when it is “enough.” This approach produces very high quality requirements and it is from these requirements that the tests are automatically generated. In fact, such thorough testing at such a rapid pace without automatic test generation is likely not possible.

Although we strive to have shipable code at the end of each sprint, this goal is not always achieved, and we may need to use the last sprint or two to stabilize the code. Since testing has already been taking place continuously before these final sprints, the application is already of considerably high quality when entering the stabilization phase, meaning risk is manageable and rarely is ship date missed.

What about Estimating?

Remember in agile it is typically ‘time’ that is fixed in the triad of time, features, and quality. In our approach also remember that, with continuous testing and the reserving of the final sprints for stabilization, quality tends to be fairly well known as well. This leaves the features as variable so what we’re actually estimating is the feature set that will be shipped.

As always, the accuracy of estimates is a function of several factors but I’m going to focus on just three

- The quality of the information you have to base estimates on,

- The inherent risk in what you’re estimating, and

- The availability of representative historical examples that you can draw from.

In our approach, estimates are made throughout the development cycle, beginning in the initial scoping sprints. As mentioned earlier, once the list of candidate features is known and expressed at a high (scoping) level, they are estimated. Naturally at this point the estimates are going to be at their most “inaccurate” for the project lifecycle, since the requirements have not been decomposed to a detailed level (quality of information). This mean there is significant risk remaining in the work to be done. Similar projects done in the past may help mitigate some of this risk and help increase the accuracy of the estimates (e.g. we’ve done ten projects just like this and they were fairly consistent in their results).

The initial estimates are key inputs to the scoping and sprint-planning processes. As the project proceeds, with each sprint risks are exposed and dealt with, requirements are decomposed to finer levels of detail, and estimates naturally become more accurate. As you might guess, estimation is done toward the end of each sprint and is used in the planning of future sprints.

What about Distributed Teams?

Today distributed development is the norm. For reasons of efficiency, cost reduction, skills augmentation, or capacity relief, distributed development and outsourcing is a fact of life. There’s no free lunch however – there are costs associated with this approach, and much of these costs are borne in the requirements lifecycle. Chief among these is “communication”. There are practices and technologies that can mitigate this issue, so that the promised benefits of distributed development can be realized. The approach in this we’ve looked at here, for example, uses the following and has been very successful:

- Concerted effort for more frequent communication (daily scrums, and other scheduled daily calls)

- Liberal use of requirements simulation via web-meeting technology

- Direct access to shared requirements models via a central server

- Automated generation of tests and reviewing these in concert with the requirements to prove another perspective of what the product needs to provide.

Conclusion

“Have you heard that England is changing their traffic system to drive on the right-hand side of the road? But to ease the transition they’ve decided to phase it in – they’ll start with trucks”.

A common mistake of development organizations making the shift from waterfall to agile is that their organization mandates they still produce their big, heavy set of documents and have them reviewed at the same milestones, clinging to these familiar assets like security blankets. It doesn’t work. As scary as it might seem all significant aspects of the approach, like documentation, need to change in unison if it’s to be successful, and requirements are one of those significant aspects.

However if you still want that security blanket and you want to have some benefit of agile, at least generate your requirements specification in an agile manner (iterative, evolutionary, time boxed, customer driven, adaptive planning) that includes simulations integrated and driven by use cases traced to feature. This is one way to reap some agile benefits without making the leap all at once.

Risk is the ‘enemy’ on software projects. High risk profiles on projects drive uncertainty, render estimates inaccurate, and can upset the best of plans. One of the great things about agile is that its highly iterative nature continually ‘turns over the rocks’ to expose risk early and often so it can be dealt with.

On the other hand, one of the great challenges for larger and distributed teams is keeping everyone aligned as course-corrections happen sprint by sprint. A big part of this is the time and effort it takes to produce and update assets and the delays caused by imperfect and strained communication. The good news is that tools and technologies now exist to produce many of the assets automatically, and to also dramatically improve communication effectiveness, allowing agile to scale.

With the right approach, techniques and technology, distributed agile can be done. We’ve done it. So can you.

Tony Higgins is Vice-President of Product Marketing for Blueprint, the leading provider of requirements definition solutions for the business analyst. Named a “Cool Vendor” in Application Development by leading analyst firm Gartner, and the winner of the Jolt Excellence Award in Design and Modeling, Blueprint aligns business and IT teams by delivering the industry’s leading requirements suite designed specifically for the business analyst. Tony can be reached at

[email protected].

References

1 The Scrum Alliance http://www.scrumalliance.org/

2 Approaches to Defining Requirements within Agile Teams

Martin Crisp, Retrieved 21 Feb 2009 from Search Software Quality, http://searchsoftwarequality.techtarget.com/tip/0,289483,sid92_gci1310960,00.html

3 Beyond Functional Requirements on Agile Projects

Scott Ambler, Retrieved 22 Feb 2009 from Dr.Dobb’s Portal, www.ddj.com/architect/196603549

4 Agile Requirements Modeling

Scott Ambler, Retrieved 22 Feb 2009 from Agile Modeling, http://www.agilemodeling.com/essays/agileRequirements.htm

5 10 Key Principles of Agile Software Development

Retrieved 22 Feb 2009 from All About Agile, http://www.agile-software-development.com/2007/02/10-things-you-need-to-know-about-agile.html

6 Agile Requirements Methods

Dean Leffingwell, July 2002, The Rational Edge

7 Requirements Honesty

Francisco A.C. Pinheiro, Universidade de Brasilia

8 Requirements Documents that Win the Race

Kirstin Kohler & Barbara Paech, Fraunhofer IESE, Germany

9 Engineering of Unstable Requirements using Agile Methods

James E. Tomayko, Carnegie Mellon University

10 Complementing XP with Requirements Negotiation

Paul Grunbacher & Christian Hofer, Johannes Kepler University, Austria

11 Just in Time Requirements Analysis – The Engine that Drives the Planning Game

Michael Lee, Kuvera Enterprise Solutions Inc., Boulder, CO. 03/09