10 Common Problems Business Analysts Help Solve

Often Business Analysts are swept up by the hustle and bustle of project life and simply do what is needed to get to the end goal. Business Analysts focus on delivering a valuable solution to business stakeholders and they forget just how much value they add by help solving many problems along the way.

This short article outlines 10 of the common problems that Business Analysts help solve in the organization and especially when helping to deliver progressive change initiatives for the organization.

In no specific order of importance, find out more about these common problems that Business Analysts help solve and see if you can recognize some as familiar problems you often help solve too:

#1 Unclear or conflicting stakeholder expectations

Stakeholders may have unclear or conflicting expectations of what a project will deliver which hampers progress and can lead to disappointment.

Business analysts can help mitigate this problem is to ensure that all stakeholders have a shared understanding of what is achievable and what the project will deliver.

A Business Analyst helps to solve this problem by facilitating workshops with stakeholders to reach agreement on project outcomes, and by creating clear documentation of requirements that can be referred to throughout the project.

#2 Inadequate resources

Many projects also suffer from inadequate resources these days, which can lead to delays and frustration. Experienced Business Analysts can help identify which skillsets are needed to help deliver a project during the planning stages of the project to ensure resources are request early during the project set up stages.

Some more ways that a Business Analyst helps to solve this problem is by monitoring project progress and highlighting to the Project Manager where risks of resource shortages may occur. Where possible Business Analysts also help to create mitigating actions to avoid potential project delays due to resource constraints.

#3 Poor communication

Poor communication is often a root cause of many problems that occur during a project. Miscommunication can lead to misunderstandings, errors, and delays.

A Business Analyst can help to improve communication by facilitating communication between stakeholders, creating clear and concise documentation, and holding regular meetings to update everyone on the project status.

#4 Unclear or changing requirements

Unclear or changing requirements are one of the most common problems faced by Business Analysts. This can cause confusion amongst team members, as well as delays in completing the project.

One way that a business analyst can help solve or minimize this problem within a project is to ensure that requirements are well-defined and agreed upon by all stakeholders before work begins, whether they are working in Waterfall projects or Agile based iterations. This can be done through creating a requirements document which outlines all the requirements for the project and getting sign-off from relevant stakeholders.

In an Agile environment, the Business Analyst can help manage this issue by ensuring that user stories are well-defined and understood by all team members before work begins on them.

#5 Lack of engagement from stakeholder

Another common problem faced by Business Analysts is lack of engagement from stakeholders. This can be due to several reasons, such as stakeholders being too busy, or not feeling invested in the project or even mistrust of the business analyst.

The Business Analyst can solve this by ensuring a clear stakeholder engagement plan is a key activity within the project. The Business Analyst can also work to build relationships with stakeholders and ensure that they are kept updated on the project status and progress.

Advertisement

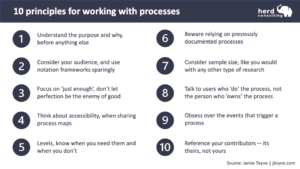

#6 Ineffective or missing processes

Ineffective or missing processes can lead to a number of problems within a project, such as errors, delays and duplication of work. This is often due to a lack of understanding of current processes being followed within the area the project is trying to solve for.

A way that the Business Analyst can help to solve this problem is by conducting a business process analysis to understand the current processes in place and identify areas for improvement. The Business Analyst can also work with the relevant stakeholders to develop new or improved processes where needed.

#7 Lack of understanding of user needs

A very common problem that a Business Analyst face is a lack of understanding of user needs. This is not because the Business Analyst is ineffective when engaging stakeholders necessarily, it can be due to several reasons including unavailability of key stakeholders and time or resource constraints that exist within the organization.

If there is a lack of understanding of user needs, it can lead to the development of a solution that does not meet the needs of the users, and ultimately will not be successful.

The Business Analyst can help to solve this problem by conducting user research and requirements elicitation to understand the needs of the users that will be using the solution. This can be done through a few methods such as interviews, focus groups, workshops or surveys.

#8 Lack of understanding of business goals

Many business analysts also find that there is a lack of understanding of business goals within an organization. This can make it difficult to align projects with organizational objectives and ensure that the right solutions are delivered. Often a Business Analyst will be assigned the task of developing a business case for a potential solution without having clear alignment of business objectives.

A way the Business Analyst can help to establish a clear understanding of the business goals is to work with stakeholders to document the business goals and objectives for the project. This can be done through workshops or interviews to understand the pain points that the organization is experiencing, and what they are looking to achieve by undertaking the project.

#9 Change fatigue

Another common yet less tangible problem faced in organizations is change fatigue. This is when staff members become resistant to change because change happens so frequently within the organizational area. This situation can make it difficult for Business Analysts who has to introduce new changes to business stakeholders and it becomes hard for Business Analysts to achieve their requirement outcomes.

One strategy a Business Analyst can follow to help manage the change fatigue of their stakeholders is to ensure that they keep them updated and engaged at the appropriate level throughout the project. They should at the same time aim to champion the benefits of the change to stakeholders and try to avoid asking stakeholders to repeat requirements or information that may have been articulated in the recent past by other Business Analysts. This is where it is very useful if Business Analysts can research similar project information to avoid rehashing the same content with fatigued stakeholders.

#10 Lack of governance

Finally, another common problem faced by Business Analysts is a lack of governance around requirements management. This can lead to several issues such as scope creep, requirements changes being made without consent or approval, and a general lack of control over the requirements. This can be a particular problem on larger projects where there are many stakeholders involved and the Business Analyst is not the only person working on gathering and documenting requirements.

A way to help solve this problem is for the Business Analyst to put in place a requirements management governance framework. This should include processes and procedures for how requirements will be managed, approved, and changed throughout the project. It is also important to ensure that all stakeholders are aware of and agree to the governance framework prior to the start of the project.

Conclusion

These are some of the top problems I could think of that Business Analysts often face and help solve. Some projects have multiple of these challenges happening at the same time which makes the role of the Business analyst very valuable as problem solver.