Unsticking Your Team’s Potential

The ‘team’ is probably the most complex and irritating relationship in an organization.

As individuals, we seem to be able to work with most people one-on-one, perhaps in groups of threes, and also as an entity of hundreds and even thousands. Where we struggle most is when there is a medium-sized group of us clustered together in a room, meeting once a month, with the purpose of, at least theoretically, doing something together.

Teams have the most trouble when there is a power differential (i.e., there is an appointed leader), and when their purpose is more strategic than operational (i.e., they make decisions vs. work on products). Most advice to teams is aimed at the leader, and what he or she can do to build a better team. Below are three membership dysfunctions that can get in the way of team effectiveness and suggestions on how team members themselves can help.

1) Team members believe the problem with the way the group is working (or rather, not working) is someone else’s fault.

Let me be clear on this point: responsibility for effective team functioning and dynamics sits squarely with the leader. However, he or she does not bear the responsibility alone. Each and every person who sits around the table is responsible for how they contribute to the dynamic. I sometimes ask people ‘what is one thing you could do differently that would help the team work together more effectively?’ and then throw up my hands in despair when I get a blank stare. The way a team member can make the team experience more positive is to reflect, answer that question, and then set about making a personal change in how they interact with their peers and leader.

2) Team members expect their leader to manage the team in a way that is consistent with the way they personally prefer to be led.

Those who want to be consulted and have decisions emerge through participative consensus-making have a difficult time with a team leader who manages in a more decisive and directive way. Team members who like direction, structure, and discipline have a tough time with leaders whose style is relaxed, opinion-seeking and open-ended.

A solution to this problem is to relax your expectations that your boss will always adjust his or her style to accommodate your preferences. While some leaders are adept at understanding and adapting to the needs of the group and the situation, not all are. The problem becomes more complex when you stop and realize everyone sitting around the table prefers something a little bit different: there is no way to make everyone happy all at the same time. Recognizing this and your leader’s limitations (and strengths) can help to elicit more empathy, and perhaps motivate you to adjust and temper your own expectations.

3) Team members expect their peers to defer to them as experts on functional issues and regard them as smarter than average on everything else.

One of the most common complaints I hear from people is that no one asks their opinion or listens when they offer it. The trouble is I hear this from every member of the team, suggesting that not only are they not being heard, they are also not listening to others.

There are two ways to address this problem. The first is to spend more time talking to each other one-on-one so you have time to fully express yourself, get a reaction from others, and evolve your thinking before you tackle the entire team with your good ideas.

The second is to be prudent around what opinions you express, how, and when. Does the team really need your personal opinion on everything? Is your input so different or so critical that it will change the direction of the conversation? Is it core to the issue or just an interesting aside? The more relevant and poignant your input, the more likely people are to stop and listen.

Teams are as unique as individual relationships. Sometimes they work like magic. Sometimes they stumble along clumsily. Most shift back and forth between these extremes. It should always be our goal to lead an effective team when we are in the position to do so. And it should always be our goal to be a member of an effective team when we are not.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below

Dr. Rebecca Schalm, who has a Ph.D in Industrial/Organizational Psychology, is Human Resources columnist with Troy Media Corporation and a practice leader with RHR International Company, a company that offers psychology related services for organizations worldwide.

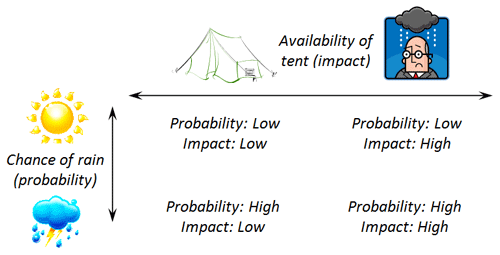

It’s the third mountain stage in the Tour de France (TdF). A few riders are in the lead as they wind their way up a mountain. The number of riders in the lead group starts dwindling – 12, 10, then 8. All of a sudden, around a hairpin bend, Jan Ullrich weaves across the road accelerating, pulling away from the pack. What will Lance Armstrong do? Chances are good that the US Postal team has thought about this risk and planned for it. This means that Armstrong will know exactly what to when Ullrich pulls this move, and the team has responded to many other risks up to this point to get Armstrong in the lead group.

It’s the third mountain stage in the Tour de France (TdF). A few riders are in the lead as they wind their way up a mountain. The number of riders in the lead group starts dwindling – 12, 10, then 8. All of a sudden, around a hairpin bend, Jan Ullrich weaves across the road accelerating, pulling away from the pack. What will Lance Armstrong do? Chances are good that the US Postal team has thought about this risk and planned for it. This means that Armstrong will know exactly what to when Ullrich pulls this move, and the team has responded to many other risks up to this point to get Armstrong in the lead group.

The practice of business analysis is only 30 years old but already we have mature methodologies, best practices, certification, tools, terminology, competencies. Our craft is in excellent shape!

The practice of business analysis is only 30 years old but already we have mature methodologies, best practices, certification, tools, terminology, competencies. Our craft is in excellent shape!