Demystifying MVPs, Prototypes and Others in the BA Landscape

Let’s get some confusion out of the way. There are many different concepts and related acronyms that aren’t always used in the best way. Let’s try to clarify them.

Terms like MVP (Minimum Viable Product), MMF (Minimum Marketable Feature), MLP (Minimum Lovable Product), prototype, and proof of concept are all concepts used in product development, but they serve different purposes and have distinct characteristics. Here’s a breakdown of the differences between them:

- Prototype:

- Purpose: A prototype is a preliminary version of a product used for design, testing, and demonstration purposes.

- Focus: It primarily focuses on illustrating the product’s design, user interface, and user interactions.

- Development Stage: Prototypes are created early in the product development process to visualize ideas and concepts before full-scale development begins.

2. Proof of Concept (PoC):

- Purpose: A proof of concept is a small-scale project or experiment designed to verify the feasibility of a particular technology, concept, or approach.

- Focus: It concentrates on demonstrating that a specific idea or technology can work in a real-world scenario.

- Development Stage: PoCs are often done at the very beginning of a project to assess technical feasibility.

3. Minimum Viable Product (MVP):

- Purpose: An MVP is the most basic version of a product that contains just enough delivery work to satisfy early customers and gather feedback for further development.

- Focus: It focuses on delivering core functionality to test the product’s intended value to the customers.

- Development Stage: MVP comes after the idea and concept but before extensive development.

- Goal: The primary goal is to validate assumptions and learn from user feedback with minimal development effort.

4. Minimum Marketable Feature (MMF):

- Purpose: MMF is a subset of features within a product that is sufficient to make it marketable to a specific target audience.

- Focus: It concentrates on delivering features that are essential to meet the needs of early adopters and generate sales or user adoption.

- Development Stage: MMF typically follows the MVP phase, where you refine the product based on initial feedback and prioritize features for marketability.

5. Minimum Lovable Product (MLP):

- Purpose: MLP aims to create a version of the product that not only satisfies basic needs but also elicits an emotional response from users.

- Focus: It goes beyond functionality to provide a delightful user experience and build strong user loyalty.

- Development Stage: MLP often follows the MVP and MMF stages and is focused on making the product more appealing and engaging.

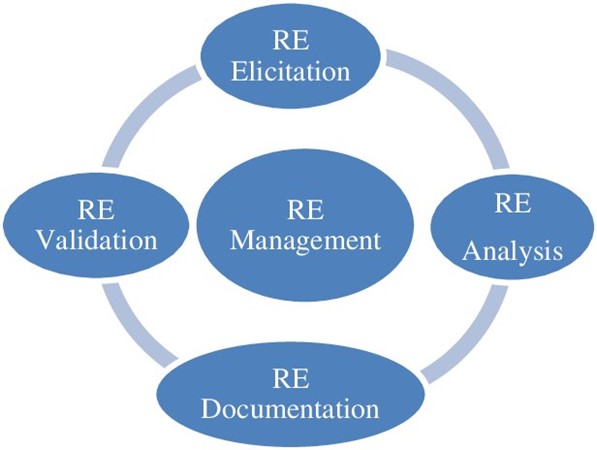

In summary, while MVP, MMF, and MLP are related to the development and release of a product, each serves a different purpose in terms of features, user experience, and market readiness. Prototypes and proof of concepts, on the other hand, are more focused on testing and validating ideas and technologies before committing to full development. In IIBA’s Guide to Product Ownership Analysis (POA®), the concepts of MVP, MMF, and Minimal Marketable Release (MMR) and Minimal Marketable Product (MMP) are introduced in terms of decision-making on what to build. The figure below is from the POA Guide and orders these four concepts. To know more about MVP with PoC and prototyping, check out a great article (with a video interview) with Fabricio Laguna (“The Brazilian BA”) and Ryland Leyton here.

Fig. 2: MVP, MMF, MMP, and MMR in the POA Guide

Advertisement

Business analysis Behind Proof of Concept (PoC)

We may use a PoC when the goal is to make a very small experiment around a business idea, from which we need to assess its feasibility.

A well-known way to explore ideas in an early phase of design is by conducting Design Sprints.

Business analysis work within this process is of extreme importance. First of all, a BA professional may use their facilitation skills to facilitate the entire workshop. When framing the BA scope to the ideation process, their work starts when applying the “How Might We” technique. If you want to know more about the “How Might We” technique, you can check it out here.

After ideating a range of “How Might We?”’s, the BA work includes facilitating the following workshops, from which the ideas are refined until a (possibly very bad) prototype is built and tested with users. BAs are usually comfortable with conducting the tests. At the end, they gather the insights from the tests and assess the PoC.

Business Analysis Behind MVP

When planning to build an MVP, don’t forget you’re targeting and validating if a business idea, through a product, has value for customers that you believe it has. However, before investing in a solid product, the mindset is that you’re making the least effort possible to have something that technically works.

This means that the work around framing a problem and further elicitation, analysis, modelling, refinements, etc. relies on hypotheses to be validated rather than fixed requirements, allowing for greater flexibility and adaptation to changing customer needs.

Business Analysis If You’re Not Targeting an MVP

Sometimes, when building an MVP, it is planned in a way that has a minimum set of features that can be delivered to customers. As already discussed, that’s not an MVP but an MMF instead, so the mindset for building it focuses more on scope modelling to decide which features have to be included.

Also, if the mindset focuses more on delighting customers (sometimes disregarding the business value delivered), that’s not an MVP but an MLP instead. The BA work focuses more on user research, interviews, and partnering (if existing) with UX/UI professionals. Personas and empathy maps are commonly used techniques.

After that, you may define your strategy to test your assumptions. There are different techniques, which depend on the testing context. And such contexts have different approaches to use.

As a BA, we can support decision-making about the technique to choose. But also to help in setting up those tests.