BABOK Version 3 vs. Version 2 – Taming the New – Guide Part 1: Knowledge Areas and Tasks

Most people in the BA field know that the IIBA® has produced an important update to its definitive Business Analysis Body of Knowledge, the BABOK® Guide. Released in April 2015, the BABOK® Guide includes major upgrades, ranging from the BA Core Concept Model™ (BACCM), to changes to most Knowledge Areas, the addition of 16 new techniques, and the addition of an all-new section containing five perspectives on Business Analysis.

By IIBA’s estimation, the BABOK has grown 50% from version 2 to version 3 and now has more than 500 pages. It has a richer and more complete set of information about the practice of Business Analysis. It also means the CCBA will have a greater amount of knowledge on which to test aspiring CBAP and CCBA candidates. Both points are good for the profession in our opinion.

Most comparisons of the two versions cover the major changes and ours is no different. However, we begin with the familiar aspects of version 2 and how they change in version 3. Part 1 features changes to Knowledge Areas and Tasks. Part 2 covers the expansion of Techniques, and Part 3 presents the two major BABOK additions: the BACCM and the Perspectives.

BABOK VERSION 3 KNOWLEDGE AREAS AND TASKS

We are starting the BABOK differences with the Knowledge Areas (KAs) and tasks instead of the Core Concept Model for two main reasons. First, most people are familiar with the KAs and their tasks, so it makes the jump to v3 a little less of a leap. Second, the BACCM surrounds the KAs and for each KA the BABOK Guide version 3 shows how the BACCM applies to it. Our view is that v3 is not as big a change as one might think when doing a KA to KA comparison.

Below is a table we compiled to show the differences in tasks. After finishing a draft we then consulted with the BABOK Guide’s table of differences and the result is shown in Table 1.

Some tasks have not changed much or at all, such as “Plan Business Analysis Approach” or “Verify Requirements. “ The task names of some 10-11 tasks have remained the same, which means roughly 21 tasks have been changed, added or deleted. There are now only 30 tasks compared with 32 in v2.

| BABOK® Guide Version 2 Knowledge Area and Task Names | BABOK® Guide Version 3 Knowledge Area and Task Names (additions/changes in v3) |

| 2.0 BA Planning and Monitoring – v2.0 tasks | 3.0 BA Planning and Monitoring – v3.0 tasks |

| 2.1 Plan Business Analysis Approach (content for prioritization and change management moved to Plan BA Governance) 2.3 Plan Business Analysis Activities |

3.1 Plan Business Analysis Approach 3.3 Plan Business Analysis Governance |

| 2.2 Conduct Stakeholder Analysis 2.4 Plan Business Analysis Communication |

3.2 Plan Stakeholder Engagement |

| 2.5 Plan Requirements Management Process (see note for Plan BA Approach) | 3.4 Plan Business Analysis Information Management |

| New Task: | 3.4 Plan Business Analysis Information Management |

| 2.6 Manage Business Analysis Performance | 3.5 Identify Business Analysis Performance Improvements |

| 3.0 Elicitation – v2.0 tasks | 4.0 Elicitation and Collaboration – v3.0 tasks |

| 3.1 Prepare for Elicitation | 4.1 Prepare for Elicitation |

| 3.2 Conduct Elicitation Activity | 4.2 Conduct Elicitation |

| 3.3 Document Elicitation Results 4.4 Prepare Requirements Package 3.5 Communicate Requirements (Note: ours is more complete than the BABOK comparison) |

4.4 Communicate Business Analysis Information |

| 3.4 Confirm Elicitation Results | 4.3 Confirm Elicitation Results |

| New Task: | 4.5 Manage Stakeholder Collaboration |

| 4.0 Requirements Management and Communication – v2.0 tasks |

5.0 Requirements Life Cycle Management – v.3.0 tasks |

| 4.1 Manage Solution Scope and Requirements | 5.1 Trace Requirements (Especially relationships) 5.5 Approve Requirements (Conflict and Issue Management; Approval was formerly an element) |

| 4.2 Manage Requirements Traceability | 5.1 Trace Requirements (“Configuration Management System” becomes “Traceability Repository”) 5.4 Assess Requirements Changes (Impact Analysis moved here) |

| 4.3 Maintain Requirements for Re-Use | 5.2 Maintain Requirements |

| 6.1 Prioritize Requirements (from Requirements Analysis) | 5.3 Prioritize Requirements (Moved from Requirements Analysis in v2) |

| 4.4 Prepare Requirements Package 4.5 Communicate Requirements (both become part of “Communicate BA Information” in Elicitation and Collaboration) |

4.4 Communicate Business Analysis Information |

| New Task: | 5.5 Approve Requirements |

| 5.0 Enterprise Analysis – v2.0 tasks | 6.0 Strategy Analysis – v3.0 tasks |

| 5.1 Define Business Need | 6.1 Analyze Current State 6.2 Define Future State |

| 5.2 Assess Capability Gaps | 6.1 Analyze Current State 6.2 Define Future State 6.4 Define Change Strategy |

| 5.3 Determine Solution Approach | 6.2 Define Future State 6.4 Define Change Strategy 7.5 Define Design Options 7.6 Analyze Potential Value and Recommend Solution (Note: ours is more complete than the BABOK comparison) |

| 5.4 Define Solution Scope 7.4 Define Transition Requirements |

6.4 Define Change Strategy |

| 5.5 Define Business Case | 6.3 Assess Risks (was an Element in v2 Business Case task) 7.6 Analyze Potential Value and Recommend Solution (Business Case is also now a General Technique) |

| 6.0 Requirements Analysis – v2.0 tasks | 7.0 Requirements Analysis and Design Definition – v3.0 tasks |

| 6.1 Prioritize Requirements (Moved to Requirements Life Cycle Management) | 5.3 Prioritize Requirements |

| 6.2 Organize Requirements | 7.4 Define Requirements Architecture |

| 6.3 Specify and Model Requirements | 7.1 Specify and Model Requirements |

| 6.4 Define Assumptions and Constraints | 6.2 Define Future State 7.6 Analyze Potential Value and Recommend Solution |

| 6.5 Verify Requirements | 7.2 Verify Requirements |

| 6.6 Validate Requirements | 7.3 Validate Requirements |

| New Task: | 7.5 Define Design Options (pulls together v2 Determine Solution Approach, Assess Proposed Solution, and Allocate Requirements) |

| New Task: | 7.6 Analyze Potential Value and Recommend Solution (pulls together v2 Define Business Case and Assess Proposed Solution) |

| 7.0 Solution Assessment & Validation – v2.0 tasks | 8.0 Solution Evaluation – v3.0 tasks |

| 7.1 Assess Proposed Solution | 7.5 Define Design Options 7.6 Analyze Potential Value and Recommend Solution |

| 7.2 Allocate Requirements | 7.5 Define Design Options |

| 7.3 Assess Organizational Readiness | 6.4 Define Change Strategy |

| 7.4 Define Transition Requirements | 6.4 Define Change Strategy (Also see Requirements Classification Schema) |

| 7.5 Validate Solution | 8.3 Assess Solution Limitations |

| 7.6 Evaluate Solution Performance | 8.5 Recommend Actions to Increase Solution Value |

| New Task: | 8.1 Measure Solution Performance |

| New Task: | 8.2 Analyze Performance Measures |

| New Task: | 8.4 Assess Enterprise Limitations |

Table 1: BABOK v2 vs. v3 KA and Task Differences (table modified from BABOK Guide® version 3)

BABOK VERSION 3 KA AND TASK SUMMARY

The changes to BABOK Knowledge Areas and their associated tasks on the surface may seem to be significant. Only one KA name (BA Planning and Monitoring) survives intact from v2 to v3. Only nine task names are the same or roughly the same. This article does not cover details like inputs and outputs, and many of those names have changed from one release to the next.

Upon closer examination, though, the changes are actually not so dramatic. We can summarize a few observations.

- Even though most KA and task names have changed, in many cases they are merely refinements rather than significant changes. For example:

- The Elicitation KA in v2 is now Elicitation and Collaboration. Most tasks in that KA are the same with the addition of the “Manage Stakeholder Collaboration” task.

- The v2 “Conduct Stakeholder Analysis” task in Planning and Monitoring has been changed in v3 to “Plan Stakeholder Engagement.”

- The Requirements Management and Communication KA and Requirements Life Cycle Management (RLCM) are essentially similar. An important addition is that prioritize Requirements is placed in RLCM.

- Enterprise Analysis has become Strategy Analysis, essentially broadening its scope. It now includes devising change strategies, transitions, and organization readiness.

- Requirements Analysis is similar in v2 and v3, despite the addition of the concept of “Design.”. An important distinction has been made by IIBA between requirements and design, which boils down to the distinction between business needs and solutions to those needs.

- Requirements – the usable representation of a need (see our forthcoming article on the BA Core Concept Mode).

- Designs – usable representation of a Solution. A new task “Define Design Options” has been added to focus on the BA work in designing solutions. Another new task “Analyze Potential Value and Recommend Solution” actually pulls together facets of two tasks from v2.

- Solution Assessment and Validation has been renamed as Solution Evaluation. There are three new tasks as the table shows. They were added to clarify the work of evaluating solution performance over its lifetime including organizational constraints.

- Out of the 32 tasks in v2, only eight have been added, a 25% change. That means 10 have been removed since there are now 30 tasks in all.

In short, BABOK version 3 is better organized than its predecessor, and with refined KA and task names contains a structure that better reflects the practice of business analysis.

In the next part of this article, we explore changes to BA techniques in BABOK version 3.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

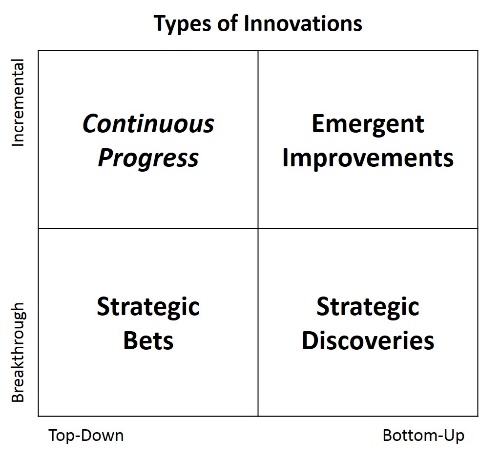

Table 1: Types of Innovation

Table 1: Types of Innovation

Welcome to the first installment of the Entrepreneurial BA series. Given we are both entrepreneurs and BAs it seems logical for to write about this topic. But, why bother? What possibly could be relevant about entrepreneurialism for a business analyst? Well, for starters, it’s a great career option and more and more viable with each passing year. Even if you are not interested in forming a start-up, the principles of entrepreneurship are becoming increasingly important for organizations to innovate and stay competitive.

Welcome to the first installment of the Entrepreneurial BA series. Given we are both entrepreneurs and BAs it seems logical for to write about this topic. But, why bother? What possibly could be relevant about entrepreneurialism for a business analyst? Well, for starters, it’s a great career option and more and more viable with each passing year. Even if you are not interested in forming a start-up, the principles of entrepreneurship are becoming increasingly important for organizations to innovate and stay competitive. Figure 1

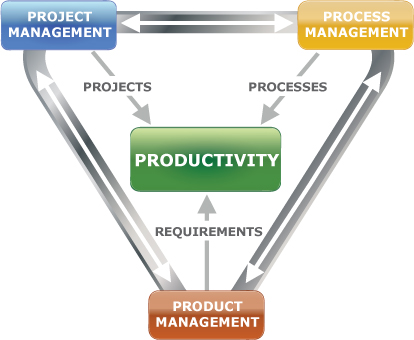

Figure 1 Business Analysis and Entrepreneurship. So, what does all this have to do with BAs being entrepreneurs you may ask? If we view business analysis work as largely product management, BAs can port those skills to creating new products for a startup. Similarly, new product development within an organization can be done in an entrepreneurial way, and business analysis skills are critical. Speaking from experience, formal project management is helpful but not as crucial for a startup. (Scrum methods are more helpful, but that is a separate topic.) Managing processes is the least important for a startup, since it won’t have processes to manage until it starts to “re-create” the products it has built. The other two legs of the triangle are essential for growing a company. Product management skills – which BAs have developed – are essential for starting a company or product.

Business Analysis and Entrepreneurship. So, what does all this have to do with BAs being entrepreneurs you may ask? If we view business analysis work as largely product management, BAs can port those skills to creating new products for a startup. Similarly, new product development within an organization can be done in an entrepreneurial way, and business analysis skills are critical. Speaking from experience, formal project management is helpful but not as crucial for a startup. (Scrum methods are more helpful, but that is a separate topic.) Managing processes is the least important for a startup, since it won’t have processes to manage until it starts to “re-create” the products it has built. The other two legs of the triangle are essential for growing a company. Product management skills – which BAs have developed – are essential for starting a company or product.