A Primer on Working with Executives:Swim with the Sharks Without Getting Eaten Alive (Part 3)

Parts 1 and 2 of this series dealt with communicating with executives and what is needed to influence them.

Now let’s move on to the 3nd key to work effectively with executives, which is that executives make decisions. That may seem really obvious so let me explain why this is one of the keys to help you avoid being “eaten alive.”

I believe that good decision-making is the main value of executives to organizations. As BAs or PMs, we can add to their value by making good recommendations and serving as trusted advisors.

The recommendations we make don’t have to be elaborate business cases, but that is certainly one way. They could be simple solutions to resolve a project issue. Or solving an ongoing problem on a task force. Or any number of other ways.

Decision-Making

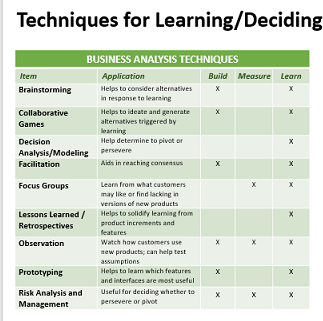

Since there are many ways and points for us to influence good decisions, I think it’s important to understand how decisions are made so we can best influence them. It’s helpful to have an effective, repeatable process to learn the right inputs for the decision makers at the right times. Let’s explore two complementary processes.

Decision-Making Process #1

First is a 7-step model published by UMASS/Dartmouth University[i] lists these steps. I included a few tools and techniques that are helpful at each step.

|

STEP |

TOOLS & TECHNIQUES |

|

1. Identify the decision |

Problem/Situation statement |

|

2. Gather relevant information |

Data, root causes, environmental factors, costs, benefits |

|

3. Identify the alternatives |

Brainstorm, Collaborative games |

|

4. Weigh the evidence |

Weighted Ranking Matrices, Decision Trees |

|

5. Choose among the alternatives |

Recommendation, Decision Analysis |

|

6. Take action |

Implementation |

|

7. Review your decision and its consequences |

Evaluation, Metrics & KPIs |

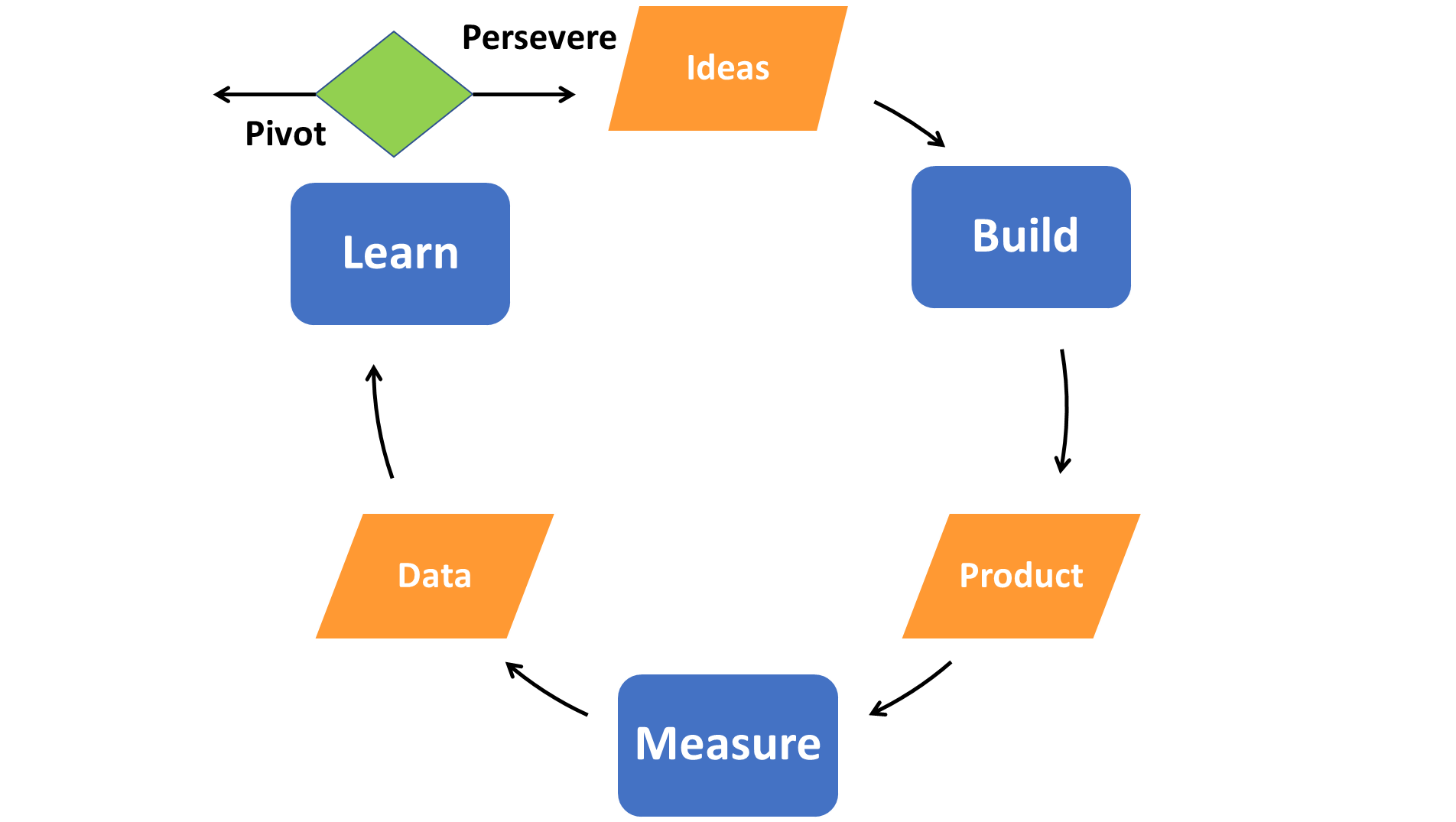

Decision-Making Process #2

Along the same lines, Watermark Learning has used for many years a simpler but similar model called SARIE. It stands for Situation-Analysis-Recommendation-Implementation-Evaluation. See Figure 1 for a diagram of the steps.

The steps leading-up to a decision are the Situation, Analysis, and Recommendation points. When I first learned about analysis, we called them “Findings and Recommendations.” But, having a clear implementation plan or strategy, and outlining how effectiveness will be measured will assist the decision. Those plans are actually part of the recommendation.

As a decision-maker at our company for years, I noticed it was easy for our staff to make recommendations, but that is the easy part. And very often they are subjective without the other steps. The hard but necessary work in this model is defining the problem and analyzing it, generating alternatives, plus how will implementation work and cost, and how will we know if it was effective?

For you blue-energy folks there are articles on the Watermark Learning web site to read about SARIE in more detail. The reason I also like that the Dartmouth process is similar to SARIE and expands it a little.

Figure 1: SARIE Process Steps

Trusted Advisors and Decisions

Let’s cover one more set of things affecting decisions by executives. Let’s say you go to the doctor’s office and step on the scale. OK, maybe not the best thought. When you use a scale, though, it’s hard to argue over weights. What I mean is some of the techniques for analyzing decisions will help us better determine acceptable recommendations. Standards like the BABOK® Guide and PMBOK® Guide list several types of decision analysis tools.

I have found two to be especially helpful and practical when making decisions in our company and with our clients.

Weighted-Ranking Tables

Weighted rankings allow for analyzing and ranking alternatives under consideration and to find the “best” alternative according to criteria important to decision-makers. See an example in Figure 2. The criteria are the key to making this tool work. Each criterion is given a weight – hence the name of the tool – and is used to compare and score each alterative in the left-hand column against each criterion in the rows across the top – Cost, Increased Sales, etc. The total scores for each alternative give the “best” one. Typically, this is the one to recommend and the one executives are most likely to accept all things being equal.

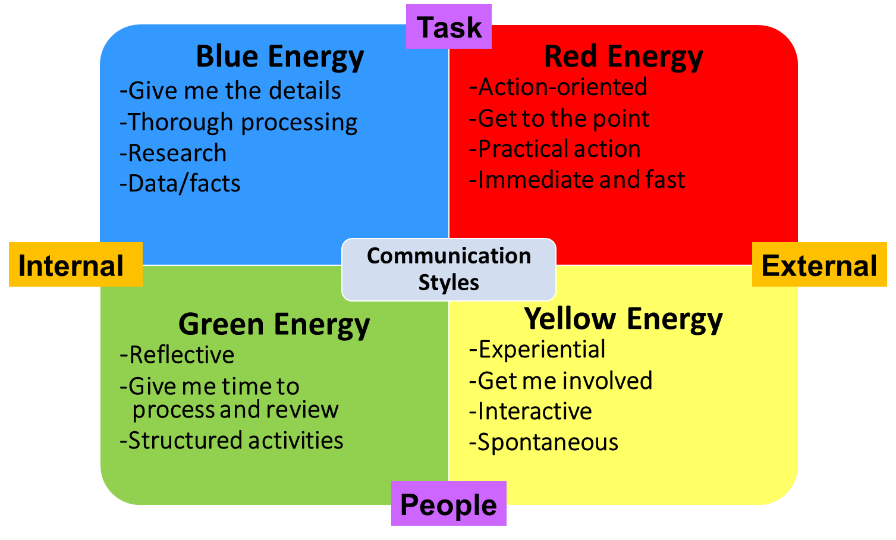

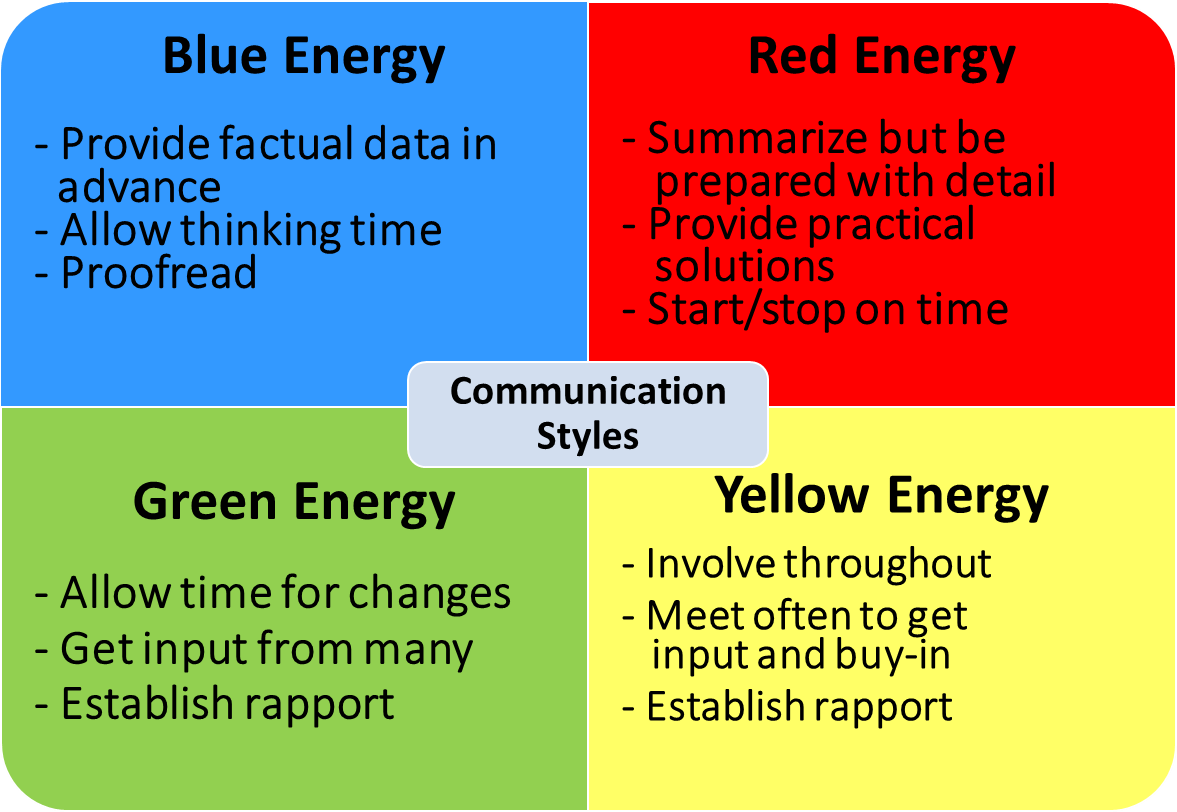

Another tool relies on what I would call “the power of four.” The color quadrants we saw in part 2 are another example and there are countless others. Many paradigms rely on combinations of two variables to explain complex issues and situations.

Decision Matrices

Decision Matrices, for instance, capture four categories of actions for solving any problem. They are useful because they help guide a team to think through different courses of action based on variables important to decision makers. See Figure 3.

They use two variables normally, and this example shows “Benefit” from high to low and “Implementation Difficulty” from Hard to Easy. I’ve seen other sets of variables like acceptance or cost, so use whatever seems to be relevant to, you guessed it, decision makers. The key is to peg alternative choices into one of the four quadrants, using some expert judgment. Normally this technique uses a continuum on both scales but this simple example is for illustration only.

Decision Matrices help us focus on business benefits over features starting with “Quick Hits” but including “Prioritize.” They are valuable allies to help executives think beyond the “low hanging fruit” or the “sexiest” choices. Last, the visual nature of this and the Weighted Ranking Table will appeal to executives too.

Figure 3: Decision Matrix Example

Summary

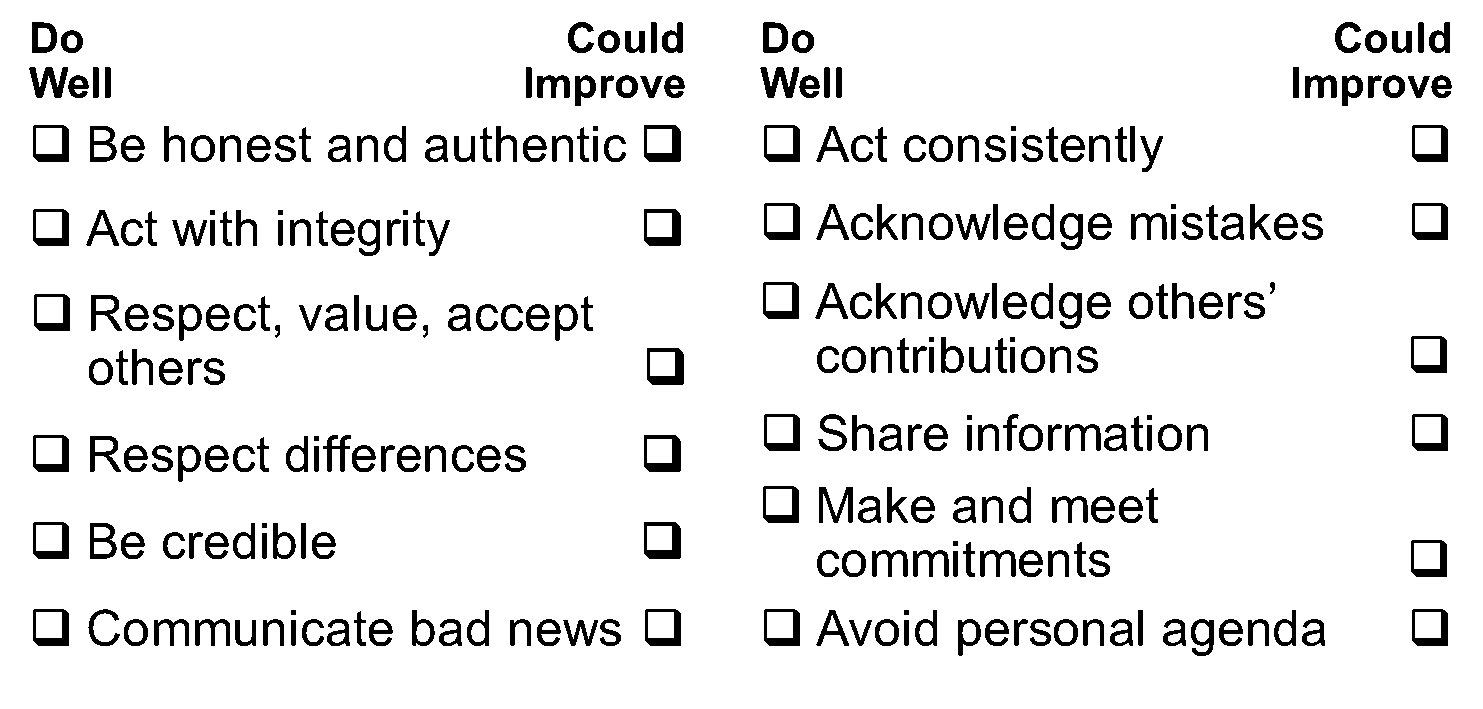

To summarize this series, when we work effectively with executives, we are serving them in a professional and consultative way as Trusted Advisors. By maintaining a “reversal of focus” and concentrating on the executive vs. our own anxiety we can reduce our nervousness and increase our confidence and value.

- I hope you can use your new knowledge of communication styles to help you relate better to executives (and build self-assurance at the same time). Matching the communication style of an executive is a great way to mirror them and put them at ease.

- The best way I know how to build confidence with executives is to make recommendations that influence them to make good decisions that lead to solutions with value. Remember the best “formula” for being influential is to build Trust, do our Preparation, and to show Courage when making recommendations. It is the essence of a Trusted Advisor.

- Finally, settle on a decision tool or two to help you pave the way for good decisions. We explored two favorites of mine but there are other good ones than can help us work more successfully with executives.

I meant for this series to be simple, recognizing it is not necessarily easy. Hopefully you will find it so and you can use the ideas to help you “swim with the sharks” in your organization.

[i] Dartmouth decision-making process, https://www.umassd.edu/fycm/decision-making/process/ – downloaded June 25, 2019