Preventing Disasters; How to Use Data to Your Advantage

The late Lew Platt, former CEO at Hewlett-Packard once stated, “If only HP knew what HP knows, we would be three times more productive.” This is a typical situation in large organizations, where far too often, disasters arise from lack of awareness. Critical information is available in the organization, but goes undetected, is not communicated or is blatantly ignored.

Take the recent mortgage meltdown, for instance. The banking industry has a wealth of data on consumers, robust credit risk models, as well as lessons learned from the past. Their analytics told them which loans were too risky according to traditional models. Yet, they decided to relax their standards, ignore the data…and the rest is history. Or, take the recent PR debacle around Southwest Airlines’ plane inspections. The FAA had inspection logs that could have told them that the planes were passing with flying colors at unprecedented rates, yet no one suggested conducting a site visit to see if the airline was actually performing those inspections. And when low-level employees reported issues to their managers, that information was not passed on. Fortunately, in that case, a tragedy was avoided.

If there is a question we should be asking in the current economic and regulatory environment, it is “Why does accountability so often fail, and what role does analytics play in preventing these disasters?” Organizations need to understand why they fail to detect early warning signs, how to filter and monitor available data to create actionable information, and how correctly applying analytics can turn data into knowledge. That knowledge can then prevent disasters and increase competitive advantage.

Why Accountability Fails

The repeated disasters that occur due mainly to failures in accountability arise for the following reasons:

- Large, complex organizations (or environments) make it difficult to know what is happening “on the ground” and detect significant changes in the environment.

- Very often, players in the organization (managers, employees, others) receive incentives only for presenting a positive picture and anchor on how things have worked in the past.

- Organizations measure and monitor only past-focused, outcome measures, which only indicate a disaster once it has already occurred.

- Many organizations lack the skills necessary to manage data, much less apply analytical techniques to make sense of that data and keep an accurate view of the current operating reality.

The Impact of Anonymity

The lack of awareness that often brings disaster stems from the anonymity that characterizes today’s organizations. A hundred years ago, most business transactions were conducted face to face. Business owners walked the shop floor. Customers who bought eggs from the village shopkeeper knew not only the shopkeeper, but also the farmer who raised the chickens. Loans where made to people the banker knew personally and regulations were made and enforced by local officials.

The more complex an organization becomes, the less transparency there is, and the more difficult it becomes to make good decisions. Consumers and producers don’t know one another. Decision makers and implementers don’t have direct lines of communication. By the time information reaches a decision-maker at the top, it is usually highly filtered, and often inaccurate. The information and implications have been spun so as not to upset management or cast dispersion on employees, and therefore fail to present the reality of the situation.

These conditions not only impair the organization’s ability to understand what is currently going on, but also remove any ability to detect change in the environment. Outside information can effectively be closed out in extreme examples. The U.S. automakers in the 1970s, who looked out the executive suite window into their parking lot and saw only U.S.-made cars, determined that Japan was not a threat. Meanwhile, dealers in California had significant early signals in their sales numbers that Japan was indeed a threat to the U.S. auto industry.

Incentives for Bad Behavior

An even more insidious problem is that disasters often arise because organizations have actually encouraged behaviors that lead to them. The filtering of information cited above is actually a very mild form of this. Employees and managers are rewarded for highlighting what they’ve done well, so why would they ever identify something that is going wrong on their watch?

We tend to blame those who bring bad news, whether they deserve it or not. Consider any major whistle-blower of the past. The amount of scrutiny, negative media attention and damage to their career is enough to dissuade most people from taking a stance. And yet those same people brought to light, and often prevented, significant disasters in the making.

So many organizations reward those who bring in good short-term results, prove out the organization’s current business model and don’t ruffle too many feathers. In return, we get exotic financial instruments in an attempt to make quarterly revenue, low standards on food or workplace safety and fudging on project and financial status reports. The contrarian voices pointing out the impending disaster go unheard and unheeded, and changes come too late to matter.

Driving While Watching the Rear View Mirror

The vast majority of the data that organizations look at represent outcomes that are past-focused. The traditional financial statements show the outcomes of business activities (revenues, expenses, assets, liabilities, etc.) while nothing in those statements measures the underlying activity that produces those outcomes. Hence, nothing gives any indication of the current health of the organization.

Kaplan and Norton sought to remedy this with their Balanced Score Card approach. By focusing on the drivers of those outcomes, the organization should be able to monitor leading indicators to ensure the continued health of the enterprise. Relatively few organizations have fully adopted such an approach, and even those few have struggled to implement it fully. Too often, managers do not fully understand how to impact the metrics on the scorecard. And as time moves on, the scorecard can fail to keep up with changing realities, suggesting relationships between activity and outcome that no longer exist.

Numeracy?

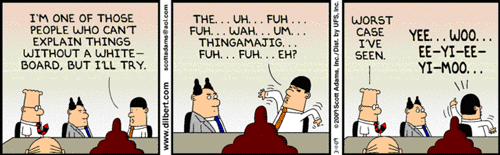

“Numeracy” is the ability to reason with numbers. John Allen Paulos, Professor of Mathematics at Temple University, made this concept famous with his book Innumeracy, in which he bemoans how little skill our society has in dealing with mathematics, given how dependent upon it we have become. Organizations today struggle to maintain a workforce that has the skills to manage the data their operations generate. Once the data have been wrangled, the analytical reasoning skills required to make sense of that data are lacking.

Analytics provides powerful tools for dealing with massive quantities of data, and more importantly, for understanding how important relationships in our operating environment may be changing. But without a strongly numerate workforce, organizations cannot apply these techniques on their own and have a very limited ability to interpret the output of such techniques. A lack of good intuition and reasoning with numbers means that many warning signals go undetected.

What Drives Organizational Outcomes?

Organizations that want to prevent disasters and increase competitive advantage first need to define what constitutes critical information – in other words, what really matters to the organization. Prior assumptions have no place in that determination. Let’s say, for example, a company is proposing to increase its customer repeat rate by increasing satisfaction with its service. But does that relationship between customer repeat rate and satisfaction with the service really exist? And to what degree? Amazon.com, for example, does not simply assume that a person who buys a popular fiction book will want to see a list of other popular fiction books. Rather, it analyzes customer behavior. Thus, someone who is ordering Eat, Pray, Love might see an Italian cookbook, a Yoga DVD and a travel guide for Bali as recommendations because other people who bought that fiction book also bought those other items.

The steps to decide what matters are:

- Decide what the organization wants to accomplish.

- Identify the activities (customer behaviors and management techniques) that appear to produce that outcome.

- Test and retest those relationships, collecting data from operations to measure the link between activity and outcome.

Once an organization has identified what constitutes its key activities, how can it find the information it needs to monitor them?

Find the points in the value chain where the key actions have to occur to deliver the intended outcomes.

- Collect critical information at, or as close to, those points as possible. The closer an organization can get to the key points of value delivery, the more accurate the information it can collect.

- Continuously look for the most direct and unfiltered route to obtain the richest, most consistent information on each key point of the value chain.

- Keep testing each assumption by asking the question, “What surprising event could I see early enough to take corrective action?”

Stop Trying to Prove Yourself Right

Several traditional ways of doing business blind organizations to warning signs of potential disasters. First among these is looking for data that confirms that all is well. Although extremely counterintuitive, it is critical to look for evidence that things are not all right. Ask the question, “if something were going to cause failure, what would it be and how can it be measured?” If it can be measured, then it can be corrected early and failure can be avoided. Rather than indicating what has gone right in the past, these measures contain warnings of what could go wrong in the future.

To see the early warning signs, follow this process:

- Ask what assumptions are being made in the process of executing strategy to deliver value. For example, if the goal is to increase the efficiency of inspections, is there an assumption that inspectors will become more efficient while still adhering to the same high quality standards? Or, in a call center, is there an assumption that reps can decrease call handle time and still provide superior service?

- These assumptions are alert points where failure might occur. Don’t wait for the final outcome, but track, measure and monitor each assumption to make sure it is playing out successfully. This process is well known to project managers. They don’t just design Work Breakdown Structures and Critical Paths and then wait around for the end date to see if the project was successful. As soon as a task begins to exceed its scope, the impact is assessed all the way down the line.

- Keep testing each assumption by asking the question, “What surprising event could I see early enough to take corrective action?”

Organizations that do this well are not operating with a negative, doom-and-gloom perspective. Rather, they want their positive outcomes so badly that they look for data that might be telling them something is going wrong so they can correct it before it is too late. They are willing to “Fail Fast” and “Fail Forward,” keeping the failure small to ensure large successes.

People Power the Process

Creating knowledge from data to prevent disasters depends on both technology and human skill. Computers are powerful tools that can help collect, store, aggregate, summarize and process data, but the human brain is needed to analyze the data and turn it into actionable information. It’s this human factor where the biggest gap exists in most organizations. Finding people who can perform the required analysis is becoming increasingly difficult. A spreadsheet is just a pile of data until someone applies critical thinking, adding subjective experience and industry knowledge to derive insights into what the numbers really mean.

Organizations must invest in developing these skills in their workforce. Here’s how:

- Provide employees with the training, job assignment, education and mentoring opportunities needed to develop their analytical skills, industry expertise and decision-making acumen.

- Subject decision-making to evidence-based approaches, providing feedback to improve future decisions.

- Ensure employees have the tools they need to manage the volumes of data they are expected to digest and act upon.

Blame Is Not an Option

In his book The Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge said that a “learning organization” depends on a blame-free culture. In other words, when a problem arises, people need to refocus from laying blame or escaping blame and start fixing the problem.

In today’s data-rich world, preventing disasters large and small requires monitoring and filtering through the large volumes of information that stream into organizations every day to find early warning signs of imminent failure. Intellectually, just about everyone will agree that it makes sense to look for what could go wrong. Emotionally, however, it’s another matter. It is both counterintuitive and intimidating to ask managers to search out constantly how the organization is failing. Establishing a blame-free culture is the final frontier to create a new awareness and encourage people to test assumptions, make better use of analytics and communicate information without fear.

Charles Caldwell is Practice Lead, Analytics, with Management Concepts. Headquartered in Vienna, VA, and founded in 1973, Management Concepts is a global provider of training, consulting and publications in leadership and management development. For further information, visit www.managementconcepts.com or call 703 790-9595.