Scope – the last frontier. We are on a mission where no business analyst has gone before. To explore strange new diagrams and to have the project scope clearly understood. Extra credit to those who remember which TV show that was from! Scope and context are the number one reasons business expectations about a project are not met and projects fail.

Let’s face the reality. Projects today are more complicated. In this integrated and connected world of systems, long gone are the days of the quick and easy change. Our organization’s architectural diagrams look like the tombs of Egyptian Pharaohs. Symbols and shapes connected by lines that fill the wall of an entire room. Even trying to explain the diagram to someone can take days.

Related Article: Requirements in Context Pt 3: Scope = High-Level Requirements

Projects now require more involvement by more people. Our systems and processes are so complex and integrated it’s too difficult for one individual to understand them all fully. Stakeholders are flung across the globe speaking many different languages. Top it off with organization’s taking on hundreds of projects at the same time. Keeping track of each project’s scope and impacts to the organization are difficult to comprehend. It’s no wonder why understanding the context of a project’s scope is the number one reason why projects fail to deliver value. They simply lose sight of the project’s vision and goals in our complex systems and processes. Everyone is one a different page. We wind up spending a lot of time trying to get stakeholders, sponsors, and team members to have a clear understanding of scope.

So it’s no wonder that scope and context are the number one reasons projects fail. How can you get an entire project team moving in the right direction? Not understanding the scope and context of a project leads to all sorts of time being spent on just figuring out what we are trying to accomplish with a project.

So how do we get everyone on the same page? By that, I mean the same page in the same book!

It’s time to visualize scope. Scope places the boundaries around where the entire project team will work. Bust out that context diagram. Getting a common, clear understanding of scope and business expectations leads to better projects that deliver real value.

Is that user story a complete representation of the project boundaries or scope? Maybe not. The EPIC or a bunch of user stories combined together would be closer to the bulls-eye. A picture is worth a thousand words. Visualization of scope is worth its weight in platinum as it creates the vehicle to ensure a common understanding of the project scope.

Scope visualization isn’t just about a context diagram. That’s certainly a great tool and I blogged about it previously. Don’t get me wrong – I love my context diagrams. Pushing the envelope a bit, I have used infographics to display project scope in place of context diagrams. In a recent server upgrade project, I was updating the operating systems and consolidating over 1,300 servers. Sticking 1,300 servers on a diagram was an exercise in futility. There just isn’t a big enough piece of paper to display them all. So I pictured things at a higher level. I displayed each server farm as a farm – yup cows and red barn with farmer Joe. The size of the farm was based on the number of servers on that farm. Server farms were in specific locations, so this gave the project team a visual representation of which sites were going to be impacted more heavily. All of this was based on estimates from doing a high-level scan. Remember context is high level.

In each barn was an icon that represented a group of servers. There were 3 groups: leave it alone, upgrade it and consolidate, then retire it. I didn’t have exact numbers or server names at this point, but I knew the servers would be divided into those groups by talking with stakeholders. Servers were put into groups based on our best guess.

In the kickoff meeting, this was a great tool. Sponsor and stakeholders understood in the scope of the project. Yes, they wanted to know more. Everyone wants to know the details, but we were just starting out. Everyone walked out of the room with a pretty good understanding of the scope and estimated size. Many were surprised at the volume of servers in each farm. Overall the infographic did a good job of setting the stage for the project visually. All on one PowerPoint slide.

The idea of scope visualization is to present a single page to provide a high-level overview of the changes the project will make to systems, processes, and people. That’s no easy task. Taking the complex and making it simple is powerful. It creates a better common understanding of the project.

The business wanted a global CRM solution, but all they got were pigeons and index cards.

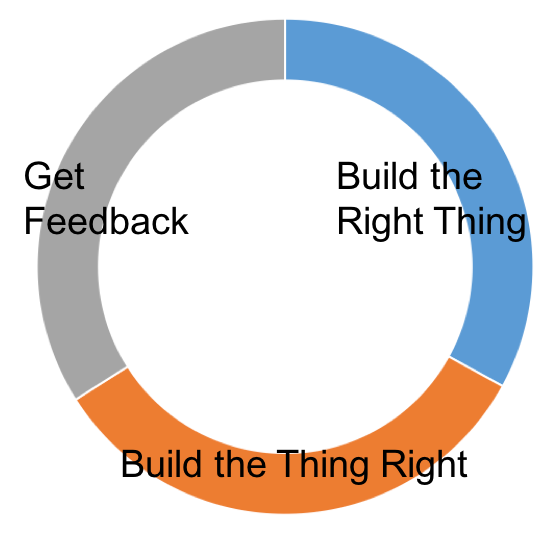

Context doesn’t just talk about scope – it also sets business expectations about the outcome of the project. It’s important to keep the communication channels open on what is happening with the scope and how the design is being implemented to meet the scope all throughout the project.

I take the concept of the context diagram a little farther than how most folks typically use a context diagram. You know me always pushing the envelope. Context diagrams usually explain the end state or the final outcome of the project. They show the scope of a project outcome.

Building on a good thing, I like to build a context diagram of the current environment at a high-level. Even at a high-level I’m often surprised at how differently stakeholders, sponsors, and team members view the current state. It’s a great tool to get everyone on the same page for the starting point. Having everyone on a different page for what we currently have will cause a few issues down the road in understanding the final destination. Knowing where you are starting from is a powerful thing when explaining where you want to end up in the future state.

Taking this concept even a bit further (and perhaps more uncomfortably) into the desired state. Not many projects really look at the desire of the stakeholders and sponsors. The desire is basically stated in the project request form or project charter. The sponsor and stakeholders put together a vision of the expected outcomes in these documents. A context diagram of the project charter or request which elaborates the vision is a powerful thing. It ensures what is being asked for is understood.

Don’t re-invent the wheel. Many times I take the current state diagram and just highlight the areas that are changing. Simply use color to highlight the add, modify or removes based on the context diagram for the current state. This visually explains where the changes are visualized to occur.

Now you may think I completely lost my mind at this point. Fear not, I’m taking a step even further. I take the context diagram that shows the desired state (based on the project charter or project request) and determine what is feasible. Everybody wants it all but the teleporter to zap you across the globe for break in Paris hasn’t been built yet. Reality always steps in and dictates what is feasible. Taking the context diagram, I highlight the areas that are NOT feasible. It’s a great way to level set the expectations of the sponsor, stakeholder, and project team members.

So when in the project lifecycle does all this context stuff happen? Ideally, it should happen before the project starts at a very high level. Wouldn’t it be great to start a project where everyone understood and was in complete agreement about the project outcome? You can bet it would save a lot of time running around trying to get everyone on the same page. Typically, the context is set at the start of the project.

As you move through the project, more and more understanding is acquired. Details need hammering out, and there is ALWAYS change to the project. Has anyone ever worked on a project with absolutely zero change? If you have, you are leading a very charmed existence. I’m jealous. Context diagrams can help evaluate how change would impact the project. So forget about laminating them and hanging them on the wall. They are living breathing documents that will change throughout the life cycle of the project.

The pitfall is that architects and others might expect diagrams that show the smallest of components. Don’t fall into that pit. Your job is to communicate the boundaries clearly but not make it so complicated a rock scientist from NASA can’t figure it out. Detail is important for design but scope context requires things to start at a very high level and be decomposed into more details. Context is simple with enough detail to make it clear.

Break out your inner Pablo Picasso and get creative. Find a way to display context or scope in a visually appealing manner. Color can help bring greater clarity. Highlight areas in different colors to bring focus to them. If a system is risky or greatly impacted by the project scope, highlighting is a technique to denote that risk. Black & White isn’t your friend. Studies have shown that color diagrams – even with a small amount of color – are more memorable.