Business Analysis Profession on its Path to Maturity

Often at the beginning of a new year, many people like to reflect upon the prior year and make plans for the upcoming year. Not only people but organizations often take on these activities of measuring the success of the past and making strategic plans for the future. A component of strategic planning is to recognize trends in the industry and to leverage those trends to the organization’s sustainability.

Since 2009, the folks at Watermark Learning have looked at the trends in business analysis and project management. Read here to see their latest reflections. In 2013, the Senior Leadership Team of the International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA®) reflected upon predictions in the profession of 2011 and then looked at what the profession may look like in 2016. Read more here to see how they did.

Not to be outdone, two years ago I threw my hat into the ring. There were some very definite trends that were in their infancy in 2014 that prompted me to recognize them. You can read what I felt was just beginning back then and see how those areas have grown and affected the business analysis profession.

So if you have read both articles who would you say is better at predicting the future, Julian Sammy or me?

I won’t go through the ten trends I identified two years ago and see how far they have come in two years. I will leave that to your assessment. However, much of the same trends from back then I would reiterate again this year—Agile, Collaboration, Product Vision, Strategy, Training, Abundance of business analysis jobs and Business Analysis Centers of Excellence.

As some of these trends continue to be identified year after year by the folks at Watermark Learning, IIBA and myself, it just goes to show that these trends continue to grow and affect the business analysis profession. As I said two years ago “Agile is here to stay.” It is not only here to stay, but it also continues to grow. It may continue to face its challenges of organizations adopting the Agile approach, but we will increasingly see organizations that previously “tried” Agile find more methodical ways to adopt the principals. This should see an increased demand for Agile coaches, certified Scrum Masters, and product owners.

Instead of reiterating these trends and possibly adding a couple to the list. I want to do what any good business analyst does and get to the root cause of the intertwining fabric of these trends.

Business Analysts Work Feverishly to Deliver Value to the Organization

Value is a concept mentioned in this year’s trends identified by the folks at Watermark Learning. It is also the intertwining concept I noticed that many of the presentations from this past Building Business Capability Conference, the official conference of the IIBA. Whether the discussion topic was Business Architecture, Business Relationship Management, Collaboration, Organizational Change, Strategy, Critical Thinking or Agile; each presentation drove back to delivering value to the organization.

IT Business Analysts, or Business Systems Analysts, will need to be innovative to find new ways and new partners with which to collaborate to deliver faster and ensure solutions that deliver greater value to the organization. Even if not adopting Agile principals, IT Business Analysts will find innovative ways to show agility in their work.

{module ad 300×100 Large mobile}

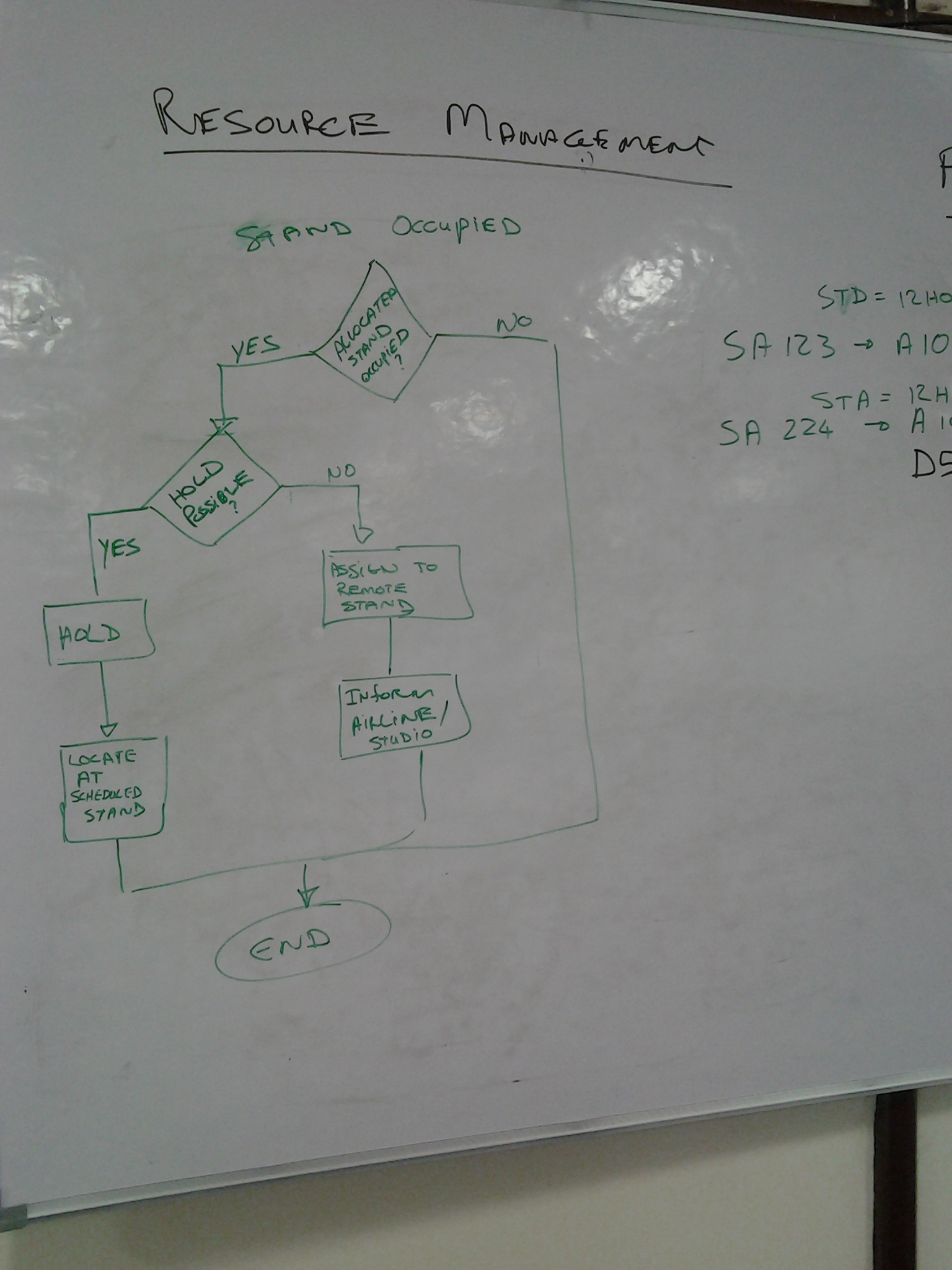

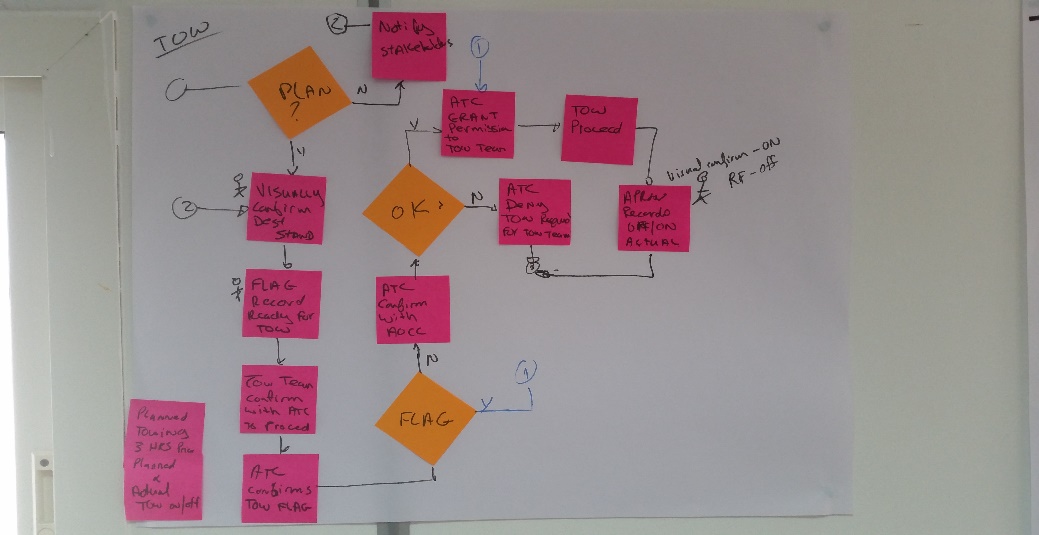

Business Process Analysts will also be innovative in their models they use to help all stakeholders understand business processes and impact of proposed changes to those processes.

Business Intelligence Analysts will work to make data more predictive and prescriptive to deliver greater value to the organization. They will find new tools to make their use and interpretation of data more innovative.

Organizations will utilize business architecture so that key decision makers within the organization can understand the business and all its components, products, and services. Business architectures will become more complete and utilize multiple views and models to aid in that understanding.

Enterprise-level business analysis practice will aid Business Analysts, in whatever role, within the organization become more agile and deliver value to the organization. Delivering value will become a key objective of Business Analysis Centers of Excellences (BACoE) and Enterprise level business analysis practices. This trend I mentioned two years ago may be slower in developing than some of the others, but it will receive refined focus in upcoming years that will aide its maturity.

The International Institute of Business Analysis will continue to support the profession and the global business analysis community. New products and services will be introduced to this end. IIBA has announced that they will revamp their certification program to a multi-level competency-based program; recognizing practitioners at progressive stages of their business analysis career. This new certification program is slated to be launched in September of this year.

Recently, IIBA announced a new Enterprise Business Analysis Core Competency Assessment Framework (EBACC) to aid organizations to assess the maturity of their business analysis practice. Then new tools, products, and services will be introduced to help mature that practice at the enterprise level. This new focus on the enterprise level will cause an increase in BACoEs.

In 2014, the IIBA was just over ten years old, and the business analysis profession was in its infancy. Two years later it might have grown to its toddler stage. Certainly in comparison with PMI, at 46 years old and ASQ at 65 years old, you can certainly see that the business analysis profession is just starting out, but in its young life, it has made some great advances. I can’t wait to see where it goes in the next ten years.