Thinking Like a Business Analyst

I was flattered recently during a meeting about a proposed merger when I was waxing eloquent, or perhaps ineloquent, about a review of the business processes and seeing how the business processes matched in each organization. I was suggesting a ‘pick of the litter’ approach. One of the directors at the meeting said that I was “thinking like a business analyst”. I doubt he was thinking about requirements or projects. The business analysts he probably was referring to were those who analyzed the businesses of organizations the company was contemplating merging with or acquiring. He may also have been accusing me of some negative attribute he associated with business analysts, but I took it as a complement, nonetheless. Regardless, it got me to thinking about thinking.

I was flattered recently during a meeting about a proposed merger when I was waxing eloquent, or perhaps ineloquent, about a review of the business processes and seeing how the business processes matched in each organization. I was suggesting a ‘pick of the litter’ approach. One of the directors at the meeting said that I was “thinking like a business analyst”. I doubt he was thinking about requirements or projects. The business analysts he probably was referring to were those who analyzed the businesses of organizations the company was contemplating merging with or acquiring. He may also have been accusing me of some negative attribute he associated with business analysts, but I took it as a complement, nonetheless. Regardless, it got me to thinking about thinking.

Thinking Fluently

The thing is that we don’t think in words, we think in pictures, images, concepts, and so forth and then translate them into words in order to communicate them. Perhaps fluency, or “thinking like…” is a matter of seeing and understanding the pictures or concepts instead of or in addition to the words. For example when you learn a second language you spend lots of time translating the words. To understand a word in the second language, you translate it first into a corresponding word in your native language which produces an image in your mind. An English speaker learning Spanish would translate “el vaso de agua sobre la mesa” into “the glass of water on the table” and then see the image of the glass on the table in her mind. A Spanish speaker would see the image in her mind immediately. When you are fluent in the second language, you are able to do the same as the native speaker: see the image without exchanging the words in your frontal cortex. Of course each of us has a different image in our heads of what a glass of water on the table looks like, but that’s fodder for another article later.

So we might conclude that if we are “thinking like” some role, or profession that we find ourselves fluent in that role, or profession, or in other words, we see the concepts and images instead of just the words. There may be other phrases or descriptions for the same thing, such as someone “getting it”, whatever “it” is, or to borrow a phrase from the current discussions of agile, “you don’t do agile, you are agile”.

Thinking like…

I think we all have roles or positions or times in our life when we can say we were or are fluent in something, other than a language. For example, at times in my life, I have felt myself fluent in several roles.

In my early years I thought like a programmer. When presented a problem. I could see the code that would be written that would solve that problem. Unfortunately, I probably suffered from what Gerry Weinberg calls the “No Problem Syndrome” in which case I was probably mentally seeing a solution in code before the problem was fully explained. Too many jumping to solutions in that way is another definition of “thinking like a programmer”.

There was also a time that I felt as though I thought like a system analyst or designer. I could see the software programs interconnecting, accessing data, and even the hardware devices on which they would reside. As an analyst I could see the pieces of a larger problem, sometimes with an inability to see the larger problem itself. As a data modeler, for example, I would think in terms of entities, relationships, foreign and primary keys, even when conducting the initial interviews with the users and business stakeholders. This, as you can imagine, resulted in some rather interesting miscommunications during the elicitation phase.

On the other hand, I was never much good at thinking like a project manager. While I had my successes in project management, there were those of my peers who could see a Gantt chart in their heads when presented with the project charter. They could mentally break down the scope into a work breakdown structure and could see the precedence network in their heads with all resources arranged and delegated amongst the tasks. I needed to go through the routine of decomposing and organizing the project with the team. I tended to think technically rather than managerially. It wasn’t ‘instinctive’ to me until I had spent many years managing, at least not as instinctive as writing code or designing systems.

Not a success guarantee, but certainly an indicator

Fluency, or “thinking like..”, is not a guarantee of success in any given profession or role. In other words, you can certainly be a success in a given role without becoming so invested in that role that your thinking is consumed by it. There is certainly evidence and cognitive behavior studies that indicate that we have predilections for fluency in certain areas. Some people have a natural ability to learn languages and the intonations and inflections that make their recitation in that language seem natural, even to a native speaker. Others struggle just to learn enough vocabulary to understand, much less speak. Similarly, some people will find it much easier to be fluent in a programming language than others. However, fluent or not, a person may be a highly successful programmer, designer, project manager, speaker of a second language, or business analyst without necessarily being fluent.

On the other hand, there is also evidence that indicates with focus, attention, practice, and intent, one can master a role, and become fluent in it, even without a predilection toward it. In the book outliers, Malcolm Gladwell suggests that one can become an expert, be fully fluent, in a role or profession by practicing that role or profession for 10,000 hours.

Regardless of whether you have a penchant for it or not or whether you are fluent in business analysis or not, you will be more successful as a business analyst when you think as a business analyst. So what does it mean to ‘think like a business analyst’?

Thinking like a business analyst

The problem with ‘thinking like a business analyst’ is that the role of business analyst is so vague. A programmer programs, she writes code that makes computers do things. A system analyst or designer analyzes problems and creates computer-based systems to solve those problems. What is the specific activity that the business analyst thinks about?

- Requirements? Can you imagine thinking about everything in terms of requirements, as in “It is dinner time, what are my requirements for dinner?”

- Documentation? Yes, the business analyst seems to do a lot of documentation such that sometimes his entire role seems to be about documentation, but thinking in documentation, as in “let me write down what I am going to wear to work today” doesn’t seem to be applicable.

- Liaison or translator between the business and IT? Your thinking might run like this: “let me explain to you what is going on with this television show, dear”. No, that doesn’t quite get it either.

Since all business analysts regardless of assignment or interpretation of the position or role are problem solvers, (the business analyst’s mission: Business, the final frontier. This is the mission of the business analyst: to go identify business problems, to seek out new solutions, to boldly go where no business analyst has gone before. [1]) perhaps thinking like a business analyst is thinking as a problem solver. Sherlock Holmes comes to mind as an example. Mr. Spock is another.

We are all born with the capacity to solve problems. Many of us let that capacity atrophy as we get older for a variety of reasons, mostly cultural and social. After all, Holmes and Spock are not the most lovable of characters. If you look at problem solving thinking, you see a number of different modes of thinking that may go into solving problems.

Critical thinking is a form of reasoning that challenges thinking and beliefs to determine what is true, partially true, or false. For example, a business analyst thinking critically would question the problem statement to make sure that it is the real problem statement and not the description of a symptom before proceeding with the analysis. Critical thinking underlies the other business analyst problem solving thinking modes. Sherlock Holmes is an example of a critical thinker, constantly challenging LeStrade’s and others’ assumptions of guilt or innocence as not being based on facts.

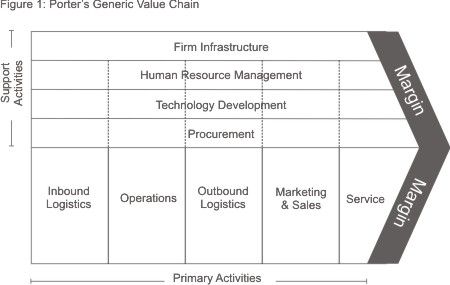

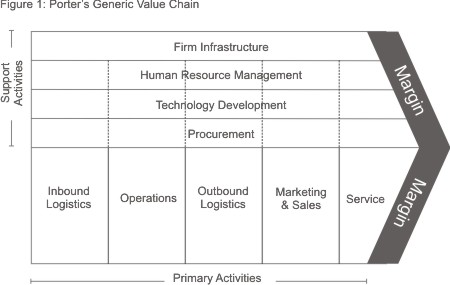

System thinking is the process of viewing problems as parts of whole systems rather than individual occurrences. The business analyst needs to view the organization and its business processes as a system or systems within systems to truly understand the impacts of the changes to the organization that the business analyst is bringing about. There have been a number of discussions on LinkedIn business analyst discussion groups lately about the application of system thinking to business analysis masterfully led by Duane Banks and Julian Sammy.

Strategic thinking as applied by an individual involves the generation and application of insights and opportunities that extend beyond the present timeframe. While system thinking provides the business analyst the larger view in terms of breadth, depth and context, strategic thinking provides the business analyst a larger view in terms of time. While strategic thinking is not usually associated with the business analyst who typically works on projects which are tactical in nature, the business analyst, being in the center of business and IT is usually in a prime position to understand the strategic implications of the projects and products on the organization.

Analytical thinking is essential to problem solving and goes hand in hand with critical thinking. Critical thinking and analytical thinking are sometimes considered synonymous. Critical thinking is specifically focused on thinking while analytical thinking is focused on everything else. Since it is often difficult to see the complete problem or the entire situation in which the problem exists given the complexities of business and technology today, the business analyst breaks the larger picture into smaller more manageable images to make examination and understanding easier. Again, Sherlock Holmes broke crime scenes down to pieces of evidence that, when put all together, assembled a complete picture of the crime and the perpetrator. This reassembly of the evidence or the pieces back into a complete whole to determine the ‘crime’ is what allows business analysts to be both system thinkers and analytical thinkers successfully. The two modes of thinking are not diametrically opposed or mutually exclusive.

Visual thinking is perhaps the only mode that might require a bit of predilection in that some people are more visual than others. But this thinking mode brings us all the way back to the initial premise that we don’t think in words, but in images and concepts: visions. To the degree that we as business analysts can visualize the problem and solution and describe that vision or render the vision into graphical form is the degree that we will be understood in our efforts to communicate.

Now that I think about it…

Thinking like a business analyst might be simply thinking first:

Thinking before reacting,

Questioning before accepting,

Verifying before assuming,

Understanding before judging,

Viewing the whole process before focusing in on the detail issue,

Analyzing before concluding,

Visualizing before writing.

While we as business analysts value the activities on the right hand side we value the activities on the left side more (to paraphrase the Agile Manifesto). Thinking like a business analyst may simply be a matter of reasoning about problems, visualizing solutions, and asking more questions.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

How would you “caricaturize” your organization?

How would you “caricaturize” your organization?

I teach a class on applying improvisation skills that focuses on how to be a better team player, collaborator and communicator. I start the class off by asking people what skills they need to be effective in their role. In this session people generally say communication skills, problem solving, negotiation skills, influence, teamwork, etc. Many of the underlying competencies in the BABOK. They also bring up the multitude of techniques familiar in our community like use cases, user stories, impact mapping, context diagrams, workflow diagrams, etc. In

I teach a class on applying improvisation skills that focuses on how to be a better team player, collaborator and communicator. I start the class off by asking people what skills they need to be effective in their role. In this session people generally say communication skills, problem solving, negotiation skills, influence, teamwork, etc. Many of the underlying competencies in the BABOK. They also bring up the multitude of techniques familiar in our community like use cases, user stories, impact mapping, context diagrams, workflow diagrams, etc. In