The Unique Competing Space (UCS) is a macro-level strategy visualisation framework, which enables teams to understand the broader scope of customer needs, evaluate how well their offerings are meeting customer needs, and evaluate how well their competition is also meeting the needs.

The UCS can easily be one of the tools in a firm or team’s arsenal for probing and situating “…the firm’s strategic position in its greater competitive context”[1].

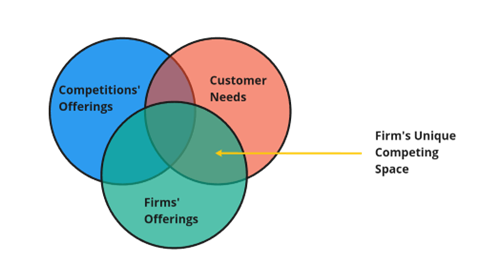

First introduced by George Tovstiga in their book Strategy in Practice: A Practitioner’s Guide to Strategic Thinking. The framework is often presented as a venn diagram consisting of three overlapping individual circles that overlap to provide a view of the firm or team’s competitive space unique to them, the opportunities open to them and the challenges on offer by the competition(s).

First each circle.

Figure: Components of the UCS framework

Customer needs:

Customers are the reasons any business is in business. They are the stakeholders whom businesses seek to serve and create value for. It is in meeting their stated, or, observed, or perceived needs that businesses indeed create value for these stakeholders, who in turn pay for the goods and or services the business has provided them. When or if satisfied, these stakeholders return to make repeat purchases as their needs may dictate and the business’ bouquet of unique offerings, prices, and customer experience may afford.

The firm’s offerings:

These are individual or collective products or services or both, that a business offers to its customers as a way of meeting the customers’ needs.

These offerings are often dictated by the alignment of the firm’s capabilities, enabling regulatory, social and cultural environments, and noted customer needs.

The competition’s offering:

Rarely is it the case that there isn’t an alternative or substitute product or service that can meet a customer’s needs other than the one offered by any one firm. This collection of offerings from one or more competing entities servicing the same market or market vertical or segment combines to make up the competitors’ offerings.

And now to the Unique Competing Space:

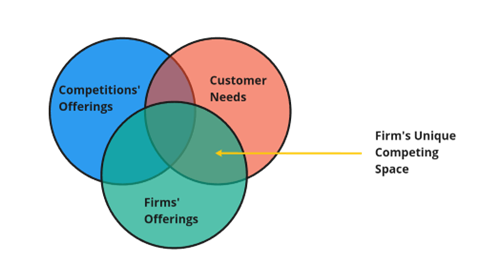

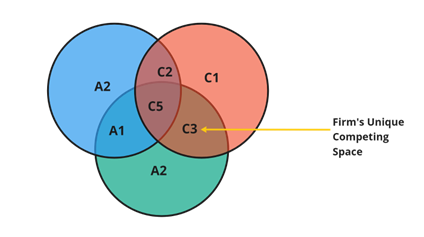

Figure2: The UCS framework

The UCS emerges when the customer needs overlap with the firm’s offering and, the competition’s offerings where those exist, are accounted for.

The portion of the Venn diagram where the customers’ needs uniquely overlap with the firm’s offerings is the firm’s UCS.

A firm’s strategic objective could be:

- to defend that space from shrinking – if it is large enough or

- to grow that space if isn’t large enough and there are potential benefits to the firm for growing the UCS or

- To exit the UCS completely if it is shrinking and there isn’t any value to the business for defending or growing the space.

Advertisement

Using the UCS:

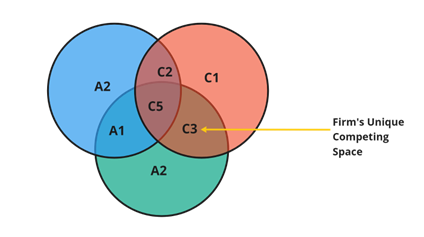

Figure 3: The UCS framework with conceptual labels

To use the UCS, it may be best for teams to gather around a large whiteboard with sticky notes (or an electronic equivalent – think Miro, Mural etc.) and then create the Venn diagram representation of the customers’ needs, the firm’s offerings or capabilities and the competition’s offerings.

On the sticky notes write down:

- All known customer needs that both the firm and their competitors are not currently meeting: place these on the part of the Customer needs component of the UCS that isn’t overlapping with the firm’s offering or the competitor’s offerings. This portion of Figure 3 is labelled C1.

- All known customer needs that the firm is currently meeting: place these on the overlapping section of Customer needs and Firm offering components of the UCS labelled C3 in Figure 3.

- All known customer needs that the firm is currently addressing and that also have alternative or substitute offerings from competitors: place these on the overlapping section of Customer needs, the Firm’s offerings and Competitor offerings components of the UCS labelled C5 in Figure 3.

- All known customer needs that are not being met by the firm, but are being met by the competition: place these on the overlapping section of Customer needs and Competitor offerings components of the UCS – labelled C2 in Figure 3.

- All firm’s offerings (and available capabilities) that may or may not overlap with those of the competitor but which are not currently being utilised to meet customer needs: and place these on the non-overlapping section of the Firm’s offerings component of the UCS – labelled A2 in figure 3.

- All of the known offerings from competitors which isn’t currently offered by the firm or meeting any known customer needs: place this in the non-overlapping portion of the Competitor’s offering component of the UCS, labelled A2 in Figure 3.

- All known competitor offerings which are also offered by the firm, but meet no known need of the customers: place this in the portion of the UCS framework labelled A1, where the Competitor’s offering overlaps the firm’s offering but both are not known to be meeting any known customer needs.

Advertisement

What to do with the information:

In general, the UCS helps the firm see the size of their UCS relative to that of the competition(s), and can provide clear inputs into the strategic choices the firm makes.

In some cases, these options include but are not limited to:

- Defend the UCS

Customers often end up churning for one reason or the other, and the goal of every business should be to retain customers for as long as they can manage and also attract new customers. When customers churn, it could only mean that the UCS shrinks one churned customer after the other, with the implication, if unarrested, of a negative impact on a business’ bottom line.So how does a firm keep customers? Listen to customers.

Observe what they love most about your products and your competition’s offerings. Ask what can come along and replace your firm’s offerings in your customer’s mind (clue – look at those things already replacing your firm’s offerings).Lock customers in (though customers protest malicious lock-ins, however, you are better off locking customers in by ensuring your offering is the most delightful to the customer). Apple had no business making watches, right? But it risks losing some iPhone users to Android OEMs who have leapfrogged the smartwatch economy and were building ecosystems between their watches and mobile devices. By introducing the Apple Watch, Apple figured out a way to lock customers into their ecosystem, whilst selling more to the same customers (people buy a phone once every two years on the average, and Apple figured out to sell to the same customers a second device which relies on the first one within the same or adjacent sales circle – both defending and growing their UCS in one fell swoop.

- Grow the firm’s UCS

Growing the UCS could require selling more to the same customers, selling to more customers or both. Additionally, it could also imply meeting customers needs that were not previously a focus for the firm but that has a great potential for cementing the existing relationship between your firm and customers. You may recall that during COVID, UberEats which was a predominantly food delivery business expanded to also deliver medicines and small packages – both of which have now become additional sources of income for UBER and in a way, has expanded the UCS for Uber.

Closing notes

Whilst most strategy teams and firms understand that having a current bird’s eye view of the competitive landscape in which they compete, the UCS may be one easy-to-use framework for doing so and carrying all stakeholders within the business along for the ride.