Summoning up the other side of the debate, here are some thoughts about why business analysis might not be a profession in itself. I am also bringing in some comments and opinions by a group of people each of whom I consider to be examples of “professional” business analysts. Ironically, they all seem to have adopted the position that business analysis is not a profession, at least for now.

As much as Mr. Blais has some good points about the profession of business analysis in the last article (Don’t Try This at Home part 1), I am presenting the opposing point of view. Business analysis is not a profession for the following reasons.

A Business Analyst for Life

When you think of the “professionals” – the doctors, lawyers, engineers, etc. – you think of people who are in that profession for their entire career and then some. A retired doctor is still thought of as a doctor. In the field of business analysis, there is a constant clamoring for the answer to ‘what next?” In articles, and around the blogosphere and discussion worlds, the question is consistently asked: “is there life after a business analyst?” In a recent series of articles Cathy Brunsting posited that business analyst was not a life long profession and suggested that business analyst “manager” or “leader: are the next steps, but offered several alternatives as ‘next steps”: product owner (for organizations engaged in Agile software development), Product Manager (for retail, manufacturing or distribution organizations). enterprise architect, business architect, account manager, and senior management. The latter has been my somewhat tongue-in-cheek response to the question of upward mobility: the business analyst is the future CEO.

All this is well and good, but it seems to argue against business analysis being a profession. The constant concern with “what do I do after I serve my time as a business analyst?” suggests strongly that business analysis is but a stepping stone or training ground for other occupations or professions. As such, business analysis cannot be a profession in itself. Doctors, lawyers, and engineers do not enter their chosen profession as a means to some other job or some other profession (with the possible exception of lawyers who sometimes practice law as a stepping stone to politics. (Although we don’t usually refer to politics as a ‘profession’ except in a purely derogatory fashion).

Who Am I?

A common thread among business analysts is to ask “what am I doing?” Questions are posted on the boards such as “what is your business analyst elevator pitch?” “What do you tell Aunt Susan when she asks what you do for work?” “What do you say to people at the cocktail party after you say ‘I am a business analyst?’ We don’t hear members of the medical or legal professions having to explain to someone what their profession is all about. A simple “I am a doctor” usually suffices. This is the earmark of a profession. While Mr. Blais suggests that the umbrella concept of business analysis having many subsets within it is a proof of profession, I see it the opposite. Until business analysis has a clearly understood and well known meaning and a clearly defined discipline to support that meaning, such fragmentation is precisely the reason it is not a profession.

The Accidental Business analyst

In one of my early articles, and my first LinkedIn post I suggested that most people practicing business analysis were like me: they got into business analysis accidentally. It was not their dream or intended career. I asked “how did you get to be a business analyst?” Most came from technical occupations while some slid over from business jobs. Some gravitated to business analysis when the organization added the occupational specialty to its job descriptions, and some were told, “you are now a business analyst, go analyze!”

The point is that unlike doctors, lawyers and engineers, none of us grew up wanting to be business analysts. We did not join the Future Business Analysts of America clubs, (In the US secondary school system, there are a number of school-sponsored organizations such as Future Farmers of America, Future Doctors of America, Future Lawyers of America, as well as clubs for budding engineers, astronomers, and other professions, including the arts.) We did not plan our education around a business analysis curriculum and get our degrees in business analysis. Such degrees are still few and far in between at the baccalaureate level and nearly non-existent in advanced degree levels.

A Degree of Business Analysis

In a conversation about professionalism in business analysis about five years ago, Kevin Brennan (Chief Business Analyst and Executive Vice President of the IIBA) suggested this definition in a tweet: “it can be taught in advance of practice, out of context”. Professions therefore are teachable whereas a practice can only be learned through doing. What is it that a business analyst can learn in “advance of practice”?

How can business analysis claim to be a profession when there are no educational criteria other than joining study groups to cram for a business analyst certification? Universities seem to be inclined to awarding certificates in business analysis rather than degrees in the subject. It was a major leap forward when some universities awarded an MBA with a specialization in business analysis. In other words, there is no professional path through the educational system to become a business analyst as there is in a recognized profession, such as law, medicine or engineering. Thus, business analysis is not a profession.

Back in 2009 Laura Brandau (bridging-the-gap.com) made some suggestions about what might comprise a business analysis curriculum leading to a profession. Last year Keith Majoos asked the same question. The answers were interesting and involved courses that many colleges don’t offer. Can you have a profession without concomitant education?

Amateur Business Analysts

If business analysis is a profession, then it should be reserved for business analysts just as the medical profession is limited to those who are legitimate doctors, and the legal profession to those who are qualified lawyers. However, we have instances of people in many other job descriptions playing the role of business analyst or simply performing business analysis. Adriana Beal (Bealprojects.com) has this opinion about professional business analysts: “I’m not sure ‘business analyst’ should be treated a profession, [but] rather a role that many of us play in various moments of our careers:” She also mentions that her husband, who is an engineer turned computer science researcher, is called upon to perform business analysis on projects on which he is working. I wonder if that would be allowed if business analysis were truly a profession.

David Wright suggests that “To me, it is not what you do, it is what you deliver. I deliver requirements, so if asked I call myself a ‘Requirements Consultant’. Some may see it as a restrictive ‘title’, but there is enough demand for the deliverable that I expect to keep doing it for as long as I want.” In other words, business analysis is not a profession, but one of many labels for those who deliver requirements

While Mr. Blais might point to that factor as meeting a condition of a profession, consider an architect who talks to the client to determine the requirements for the new home he is designing for them. Or the engineer defining the requirements for the bridge he is building. Or consider a moving contractor analyzing the contents of all the rooms and closets of your house to define the requirements for boxes, truck space, and men to get your belongings transported to another dwelling.

Are any of these business analysts? Mr. Blais might point out that while they are defining the requirements or doing business analysis activities, they are actually playing the role of the business analyst. He might also stress that the fact that other job titles are aware that they are performing business analysis activities is enough to substantiate business analysis as a profession. Mr. Blais might jokingly refer to those who play the business analyst role while performing another job description as ‘amateurs’ to distinguish them from those who perform the same tasks on a full time basis and in that way prove that business analysis is a profession. I argue that a ‘profession’ requires specific and specialized knowledge and expertise such that only those who part of the profession can actually practice it. No “amateurs”. We certainly don’t think of people playing the role of lawyer or architect at various times during their lives as the need develops, except, of course, in the movies.

Not only That…

I can hear Mr. Blais protesting that if business analysis is not a profession, what is it? Is it part of another profession? Certainly there is no profession of “business” although there are those who seem to believe that an MBA is a profession, although I am not sure what a “professional MBA” is.

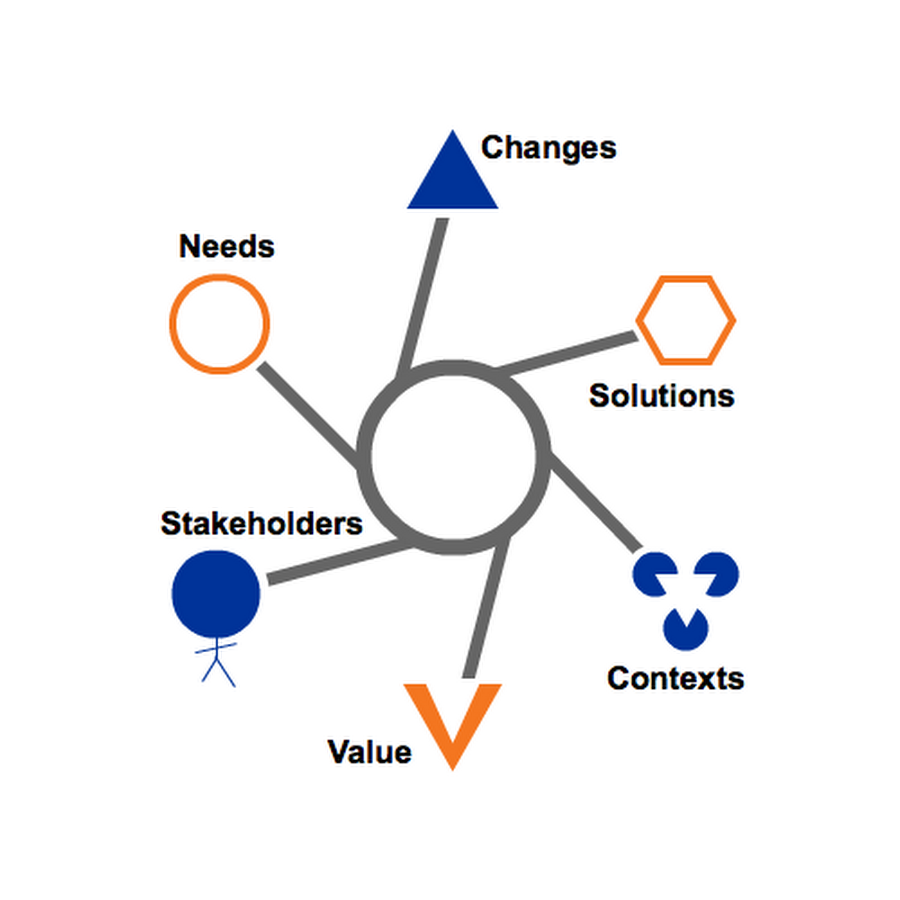

Currently business analysis seems to be a part of many other professions. As Adriana and others have pointed out, project managers, software engineers, quality assurance specialists, stock brokers, etc., use the techniques laid out in the BABOK and other business analysis guides. So, I would submit that business analysis is a practice or collection of practices rather than a profession. Or, as Mr. Blais has said, the business analyst is a role to be played by anyone, perhaps without knowing they are playing it. And maybe that is where it should stay.

Duane Banks takes it one step further: “I’m beginning to see business analysis as something you do, akin to critical thinking. So, business analysis is a skill or a competency.” Not a profession, not even a practice, but a competency!

There is one more aspect that Mr. Blais does not mention, business analysis does not yet has an enforceable set of professional ethics and guidelines that as there is in other professions. A lawyer can be disbarred, a doctor lose her license to practice, There are boards and adjudicators and sometimes even laws to help police the profession, weed out the miscreants, and maintain the overall reputation of the professionals. As of now there is nothing of that sort for business analysts or those practicing business analysis. All business analysis has at this time is certifications, and a certification linked to experience does not a professional make.

And Yet…

While I join with the others who posted comments to Mr. Blais’ article last month in suggesting that business analysis is not a profession I am not saying that business analysis should not or cannot be a profession.. I am saying that it is not now, or perhaps it is not yet.

So, what is necessary for business analysis to be considered a profession alongside doctors, lawyers and engineers?

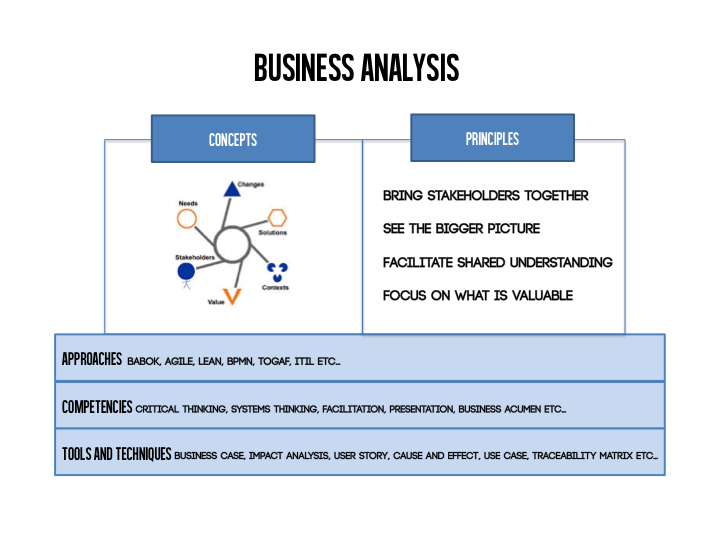

The fledgling business analysis profession must coalesce on its definitions and identify its own scope. The IIBA has released its new core purpose and that purpose seems to suggest a movement toward consolidating and codifying the central purpose for business analysis to create a set of principles similar to the Hippocratic Oath or other professional creeds. This will provide a unifying connectedness among all those who choose business analysis as a profession. In addition, the Project Management institute is preparing a Practice Guide to Business Analysis which defines aspects of business analysis as it applies to making projects successful. These two efforts, among others, may help create a single consolidated understandable definition of business analysis so when I say at a cocktail party “I am a business analyst,” people will immediately understand what I do. That will go a long way to gaining a seat at the table of professionals.

The education systems need to create the necessary professional preparatory training. Perhaps there might be a tie between the MBA and the business analyst. In other words, there must be some curricula for undergrads and graduate students to take that leads to a degree in business analysis. The preponderance of the course work would be in business and not in technology, focusing on communication skills and analytical techniques rather than defining requirements.

As business analysts we would need to somehow establish a set of guidelines for behavior and ethics that is enforced. This might bring up the concept of licensing and that might bring up the specter of government involvement, but that seems to be a part of the definition of “profession”, at least at the doctor-lawyer-architect-engineer level.

But most of all those who are business analysts and who are practicing business analysis have to believe that they are in a profession, that business analysis is a destination and not a step along the way to some other position. We need to stop being apologetic for being business analysts. We need to understand the valuable and indispensable service we provide to the organization we work for. We need to establish high standards for performance and behavior among business analysts and adhere to those standards ourselves.

I do, however, agree with Mr. Blais about one thing: there is an opening and to a degree, a need, for a profession for the business domain to match that of the medical and legal and engineering domains. And it could be, and perhaps should be, business analysis. While we are not a profession yet, we can be if we want it to be.

As I said in an answer to the question: “Is the business analyst a stepping stone to other positions?” after a long series of positive responses that listed what those ‘other positions’ might be: “Gee. I like to think that all the career changes lead a person to the ultimate position, that of business analyst. There is nowhere to go from there but down.”

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

There’s a fine line though. Bear with me, I won’t suffocate you… yet. (via

There’s a fine line though. Bear with me, I won’t suffocate you… yet. (via

Do you even Excel, bro? (via

Do you even Excel, bro? (via