Are Business Analysts In Danger of Becoming Extinct? Part 2

The response to my article has been overwhelming to say the least. I was pleased to see the genuine interest and passion in support of the role and profession of the business analyst. The many differing viewpoints in and of themselves tell a very interesting story, perhaps worthy of another article?

As I reflected on all of the comments, it occurred to me that the forest had been overlooked for the sake of the trees…the technical trees. Many of you responded with concerns, support and very pragmatic viewpoints where “technical competencies” are concerned. It’s unfortunate, and a challenge BAs and stakeholders alike face every day. However, my intended message was clearly lost in translation. When I referred to “technical competencies”, in the context of the article, I was specifically addressing those tasks, activities and techniques referenced in the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge®, as presented by the IIBA, and NOT “technological competencies” as they relate to the information technology world.

I hope this clarification will perhaps give a moment of pause and reflection before reading Part 2 of this article, I’m more curious than ever to hear your thoughts, feedback and input.

In this article, I continue my mission to raise the alarm to the potential extinction of the business analyst by emphasizing that regardless of the BA’s professional level, we need to demonstrate quantifiable impact. As I wrote in Part 1 of “Are Business Analysts In Danger of Becoming Extinct? A Perspective on Our Evolution,” I explored the context for the reasons BAs need to use a balanced portfolio of technical and business skills in order to demonstrate their value to the organization. In this article, we’ll examine the appropriate mix of skills based on the BA’s level of experience.

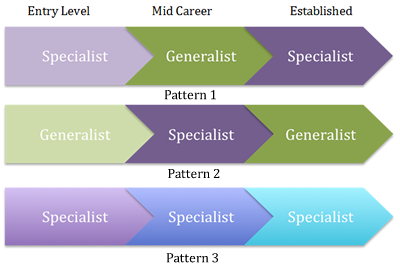

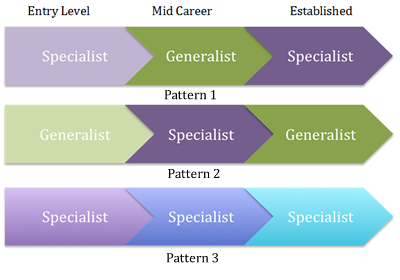

When we set out on a career path, whether it’s police officer, writer, painter, etc., we are rich with technical knowledge and competence, doing a lot of work “by the book.” As we become more experienced and more seasoned, we find our own rhythm, shortcuts and better ways to do things, and come to rely more on our business savvy and skills as we inevitably begin to direct others in performing the technical aspects of a job.

In the beginning of their careers, business analysts start out with the IIBA Body of Knowledge® and any other materials they can get their hands on as reference for drawing diagrams, researching templates and other technical questions. The new BA relies extensively on skills around requirements analysis and elicitation practices as the core essentials. This requires a high degree of technical fluency; for example, elicitation from a technical perspective requires planning and stakeholder analysis using a variety of different techniques to realize requirements from all perspectives.

In order to conduct elicitation activities with a high degree of accuracy, the BA needs to be aware of which ones, e.g., brainstorming, interview, focus group, survey or questionnaire, are most appropriate. Knowing which method is right and selecting the most appropriate technique increases the efficiency and effectiveness of that activity.

For example, using a survey/questionnaire of 300 people in 10 days of effort using 600 hours as opposed to conducting 300 interviews requiring 1,200 hours is an example of creating an efficient solution that can quantifiably show positive impact on the project. This kind of quantification gives the BA evidence to provide to executives to justify the recommended activity. It also provides the opportunity to demonstrate the cost of not conducting the activity—and, if done properly—the opportunity to:

1. Quantify the results of the survey through carefully crafted questions that would ask stakeholders to rate and rank anything from wants and needs to priorities.

2. Vote on the allocation of requirements based on said data.

The same can be said of requirements analysis—creating the right models, sequences with the right degree of accuracy, plan for activities—these are all technical skills that provide opportunities to show quantifiable impact.

As BAs develop further along they look more at the big picture—how the business runs—and perhaps leave the more technical aspects to another BA or team. Having a mixed balance of both is critical to enable oversight and examination of the work being done, while being able to practically apply career experience based on business skills. So, while the more experienced BA is knowledgeable in both, he or she doesn’t necessarily execute both.

Moving beyond junior technical, worker bee-type of activities, the more experienced BA progresses to the intermediate level where he or she puts a toe in the water with activities such as planning and monitoring. This is where business skills start to come into play to answer questions such as when and what activities need to be done and who are the stakeholders that need to be considered?

Transitioning into a senior role, the BA is acutely aware and well seasoned in technical skills and begins to flex business skill muscle in enterprise analysis-type activities, e.g., writing a business case, understanding business needs, conducting capability analysis, defining solution scope.

What’s the right mix?

It’s helpful to have an idea of the percentage mix of technical and business skills the BA will use throughout the career spectrum:

|

Career level |

Ratio of technical to business skills |

Competencies of focus |

| Junior | 80/20 |

Elicitation and requirements analysis activities and techniques, ability to practice solution assessment and validation activities |

| Intermediate | 60/40 |

Planning, monitoring, and management of requirements + junior level competencies |

| Senior | 20/80 |

Enterprise analysis + a high degree of business skills expertise, e.g., critical thinking, problem solving, change management, high impact communication |

Given the range of skills sets practiced at each level of experience, the 80/20 rule using a mix of junior, intermediate and senior levels of BAs in the organization is recommended: 80 percent junior and intermediate level and 20 percent senior level. This will create a balance of business analysis capability based on experience, not headcount. It also facilitates a well-rounded BA perspective. For instance, if an organization is top heavy on the senior BA side, there’s the risk of potentially losing objectivity and creativity without junior or intermediate BAs to question or bring a differing point of view.

The levels of experience align essentially with three layers of the BA’s impacts:

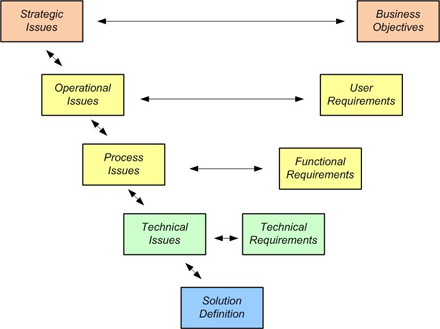

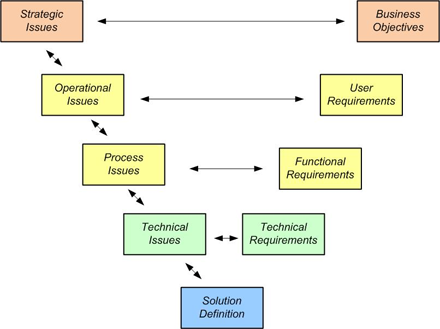

- Organizational level – This level addresses issues such as key performance indicators, goals and visions, which are typically manifested by a senior BA conducting senior business analysis type activities. An example would be using enterprise analysis to contribute to the development of a solution that increases profitability by a certain percent.

- Practices, standards, methods and approaches – At this level, intermediate and senior BAs are seeking to create efficiencies within their practices and processes. They address issues such as how can we do this faster, better? How can we refine our approach/methods?

- Activities – This level is task focused, seeking improvement of junior level practices, asking questions such as “can we be more precise?”, and “can we be more efficient with our technical activities?”

The business analyst profession continues to be a work in progress. To keep BAs from going the way of the dinosaur before they’ve had a chance to completely mature takes a balance of skills. With a greater understanding of how BAs can demonstrate their impact and value to the organization with a portfolio of competencies, you’ll better serve your professional development while elevating the business analysis profession too.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below.

Glenn R. Brûlé, CBAP, CSM, Executive Director of Global Client Solutions, ESI International, brings more than two decades of focused business analysis experience to every ESI client engagement. As one of ESI’s subject matter experts, Glenn works directly with clients to build and mature their business analysis capabilities by drawing from the broad range of learning resources ESI offers. A recognized expert in the creation and maturity of BA Centers of Excellence, Glenn has helped clients in the energy, financial services, manufacturing, pharmaceutical, insurance and automotive industries, as well as government agencies across the world. For more information visit www.esi-intl.com.

Most organizations have an understanding of the value of business analysis and what requirements mean to a project. At the same time, conditions are emerging that have the potential to undermine the position of the business analyst to the point of extinction. In this first part of a two-part article, we’ll take a closer look at what has brought these circumstances about in order to provide a clear understanding of why BAs need to balance their technical and business skills and demonstrate proof of their value to the organization.

Most organizations have an understanding of the value of business analysis and what requirements mean to a project. At the same time, conditions are emerging that have the potential to undermine the position of the business analyst to the point of extinction. In this first part of a two-part article, we’ll take a closer look at what has brought these circumstances about in order to provide a clear understanding of why BAs need to balance their technical and business skills and demonstrate proof of their value to the organization.