What is the Future for Senior Business Analysts?

Now that you are recognized as a senior business analyst, what can you look forward to in your professional future?

Now that you are recognized as a senior business analyst, what can you look forward to in your professional future?

BAs who have ten or more years of experience often feel “topped out” in their career path because most companies assume that senior BAs will develop into something else, such as a project manager or product manager. If a business analyst wants to extend herself beyond a single business function or provide more consultative guidance to her business unit, she typically has to change roles and embark on a different career path. Once a BA’s head has hit the company’s career path ceiling, there is often no place to go but to another company for advancement. Even so, most companies do not have a growth path for a business analyst who is already senior.

In this article, we will look at options for our professional future and talk about ways to extend ourselves professionally.

Where BAs Come From

Many of us came to have the business analyst title through roles such as

- Power User

- Developer (or “Programmer”, or “Systems Analyst” to use the old-fashioned terms)

- Quality Assurance Analyst

- Database Administrator

- Technical Support, Customer Support specialist

- Infrastructure (IT) specialist

Managers recognized that in addition to our remarkable analytical skills we had special qualities, such as our ability to ask questions about the big picture, or our ability to be the communications bridge between a customer and the technical team, or be the communications “hub” for the entire technical team. We found ourselves playing the role of the business (systems) analyst whether or not we had the title.

Currently the typical growth path for a senior BA is to become a

- Project Manager

- Product Manager

- Account Manager (internal customers)

In some companies, a senior BA can add the following titles to their list of possibilities:

- Architect

- Business Process Analyst

In my humble opinion, one of the best things a BA can do for him/herself is to get savvy about process analysis. If your current position keeps you focused on the details, consider coming up for some air, learn to analyze the processes that are generating the details and the predictable system failures that you are drowning in. Maybe the root of the problem is not in the data itself but in the processes around the data.

Maybe you are already spending a lot of time with the system architects in IT, and the business architects on the business side of your company. Architecture is the art and science of designing structures whether they are physical or logical. With all of your experience, you may be at a point in your career where you’re ready to focus on design.

Jonathan Kupersmith’s blog article, “What?! You Don’t Want to Be a Project Manager” summed up the BA to PM transition controversy quite nicely. Product manager and account manager both have the word “manager” in the title; some people assume that becoming a manager of some sort is the only way to show that you have achieved success. Let’s say that you are an iconoclast, not driven by what other people think or the strictures of your country’s norms – you don’t want to be a manager, you want to be recognized as a senior business analyst and you want career growth. Is that so much to ask?

What Does it Mean to be Senior?

Being senior is more than just “years on the job”. Being a senior BA implies:

- Mastery of core business analysis competencies and corresponding skills

- Both breadth and depth of knowledge and experience

- Knowledge of business processes

- Leadership

The IIBA identifies these categories of core competencies, called underlying competencies in the BA Body of Knowledge (BABoK):

|

|

These competencies have nothing to do with domain knowledge; these are the competencies a BA brings to every job assignment. The skills that correspond to these competencies are:

|

|

As a senior BA, you may or may not have equal levels of mastery of these skills. The three aspects of being a leader as BA that I want to call out are, being an agent of change, being a speaker of truth, and being a role model. These three aspects are key for senior BAs to set their sights on what the BA Body of Knowledge calls “Enterprise Analysis”.

Being acknowledged as the “go to” person in your group can feel great because you can share your experience and knowledge with others. Being senior can also bring on an empty feeling. Most BAs need new challenges; we need to keep learning; we can’t survive on the same old problems. No one wants to live with an old leaky faucet; not only does the dripping sound drive us crazy at night but knowing that water is being wasted without taking action is morally wrong. We BAs need to find satisfying ways to apply our brain power.

Kathleen Hass has written a wonderful book, From Analyst to Leader – Elevating the Role of the Business Analyst. I recommend this book both to business analysts and managers of business analysts because Ms. Haas and her contributors have accomplished an impossible task, they have articulated in just 120 pages what leadership means for a BA in the two overall contexts that a BA may work in: a project, and a business solution life cycle. Moreover, there is a chapter on establishing a Business Analysis Center of Excellence.

Next Steps

As a senior BA who is feeling that the ceiling is coming closer and closer to the top of your head, how do you extend your knowledge and experience range? Think about this in terms of how big a step you want to take, a small step, a mid-sized leap, or a big leap.

- Small step

Stay within your general domain (or business process) but add a new, closely-related sub-domain (or business process) to complement your existing specialty area.

- Mid-sized leap

Extend your activities into a new domain within your current business unit, so that you can take advantage of the trust-based relationships you have with senior and executive managers.

- Big Leap

Extend your activities into an unrelated domain where you will have to build new relationships with managers and single contributors. This kind of leap is not for the faint of heart.

Let’s look at an example.

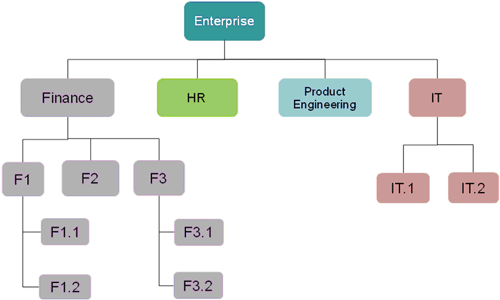

A small step would be working in Finance where you are a Senior BA in sub-domain F1.2, and taking on activities or responsibilities for closely-related sub-domain F1.1.

A mid-sized leap would be working in Finance where you are a Senior BA in sub-domain F1.1 and taking on activities or responsibilities in related sub-domain F3.1.

A big leap would be working in Finance and taking on activities where you must learn about the IT infrastructure that supports the business applications used in Finance.

Here’s what you need to think about as you decide how much you want to start extending yourself:

- What is your risk tolerance?

- Do you trust your command of the core competencies?

- How fast do you absorb new information?

- How fast do you build allies?

- How badly do you want to influence improvement?

As a senior BA, you are a subject matter expert. Do you remember what it feels like to “not know”? What is your tolerance for “not knowing”? What is your tolerance for not having allies? Will your ego allow you play the “I’m new, please forgive me if I don’t know how this works and I have to ask a lot of questions” card. If you dive in and the waters are too deep, will it be okay for you to take a step back? The more comfortable you are with “not knowing”, learning new information fast, building new allies quickly, the bigger the leap you can take.

When you have answered these questions for yourself, determine how to frame your request to expand your activities in a manner that shows your manager that you are thinking about the benefit to the company, not just your career path. As a senior BA you are probably quite well aware of where there are needs in your company.

Enterprise Analysis

Defining a business need and making the business case for finding a solution to meet that need is heart of the BA BoK knowledge area called Enterprise Analysis. The tasks involved in this knowledge area are defining the business need, assessing the capability gap, determining a solution (high-level) approach, defining the solution scope (high-level), and defining the business case. The IIBA identifies the following skills for this knowledge area:

|

|

I would add “writing a business case” to the list of skills as a business case is a well-understood documentation artifact that has a commonly understood structure and content. Typically, senior BAs have competence in some but not all of these skills. Senior BAs take note – when you are thinking about where you want to expand your knowledge and experience, think about the skill development you will need. Just like changing the batteries in the smoke detector in your home when we switch to daylight savings time, the beginning of the year is a good time to update your professional development plan – what do you want to accomplish this year? Your manager may not be able to respond immediately to your request with a new assignment, but your manager may be able to approve training for you in anticipation of helping you take on a bigger challenge.

Summary

We started with the question, “What is the Future for Senior Business Analysts?” We made the assumption that you don’t want to be a manager, and you are perfectly happy being included in architectural discussions but you like being a business analyst. There are two issues here, the first is your skill set, the second is your title. With respect to your skill set, think about adding or improving the Enterprise Analysis skills listed above. Also think about adding process analysis and process engineering to your tool kit.

The thornier topic is your title because job titles are defined by your company’s Human Resources group. Enlist your manager’s help – ask to see the job descriptions for business analyst positions for all grades. If you are truly “topped out” in your grade level, ask If there is job structure for another role that could be used to create a career growth path for senior BAs. For example, what is the highest position that a single contributor in the engineering organization can achieve? Could that model apply to the business analysts? It may take some time and considerable energy from your manager to help HR understand the need to create “head room” for a job family that was not envisioned to support senior contributors. We senior BAs need to influence this change both for ourselves and for the BAs who are going to be turbo-charged in their development, thanks to existence of the BA BoK. The next ten years will do more than set precedent; the next ten years will establish a standard practice of cultivating talented, battle-hardened and business-savvy BAs to share their knowledge and experience with the entire enterprise.

Don’t wait for the business analyst job structure to catch up. Get out there and be the role model for what you believe a senior BA can do. Take it one step or one leap at a time.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below

Cecilie Hoffman is a Senior Principal IT Business Analyst with the Business Analysis Center of Excellence, Symantec Corporation. Cecilie’s professional passion is to educate technical and business teams about the role of the business analyst, and to empower the business analysts themselves with tools, methods, strategies and confidence. Cecilie is a founding member of the Silicon Valley chapter of the IIBA. She writes a blog on her personal passion, motorcycle riding, at http://www.balsamfir.com. [email protected].