From Tactical Requirements Manager to Creative Leader of Innovative Change

The Adaptive Business Analyst – As Complexity Increases, the BA Adapts

The world, she is a’changin’. The Internet has made everyone on the globe hyper-connected and has transformed virtually all industries: publishing, broadcasting, communications, and manufacturing. Did you know that just a few short years ago:

|

|

Didn’t exist |

|

|

Was a sound |

|

|

Was a prison |

|

A Cloud |

Was in the sky |

|

An Application |

Was something you used to get into college |

|

4G |

Was a parking space |

|

Skype |

Fast forward to now. Traditional work has been commoditized. Anyone with an idea and a little moxie can use their laptop to set in motion a virtual new entity. You can go to:

|

Taiwan |

For product design |

|

Alibaba in China |

For low-cost manufacturing |

|

Amazon.com |

For delivery and fulfillment |

|

Craigs List |

To do your accounting |

|

Freelance.com |

If this isn’t bad enough, the heart and soul of middle class jobs are disappearing in the U.S. Consider this: When Apple began manufacturing the iPhone, the company estimated that it would take nine months to find 8,700 qualified industrial engineers in the U.S. to oversee and guide the 200,000 assembly-line workers eventually involved in manufacturing iPhones. In China, it took 15 days.[3] Result: we lost 200,000 iPhone manufacturing jobs.

Many believe that these and many other traditional jobs are not coming back to the U.S. So, what are the jobs of the future? We probably don’t even know what to call them, but they will definitely require creativity, innovation, invention, and lots of complexity. Even today, many companies in Silicon Valley do quarterly reviews of their key project leaders because they can’t wait to find out they have a poor BA or PM. Many U.S. companies report they can’t find the employees they need. American businesses also report that U.S. workers that are available are too expensive and too poorly educated as compared to workers in India, China, South Korea and many other countries.

What does all this Mean to the Business Analyst?

Employers are looking for critical thinking and an ability to adapt, invent, and reinvent; collaborate, create, and innovate; and an ability to leverage complexity to compete. Standout companies are using projects as the hotbed of creativity – so that means BAs and PMs have to step up their game. According to the 2011 CHAOS Report from The Standish Group, only 37% of projects delivered on time, on budget, with required features and functions.

- The Cause: Gaps in enterprise business analysis and complexity management

- The Cost: USD 1.22 trillion/year in the US and USD 500 billion/month worldwide in IT project waste

- The Opportunity Cost: “If we could solve the problem of IT failure, the US could increase GDP by USD 1 trillion/yr.” according to Roger Sessions, a recognized expert in enterprise architecture and author of Simple Architectures for Complex Enterprises.

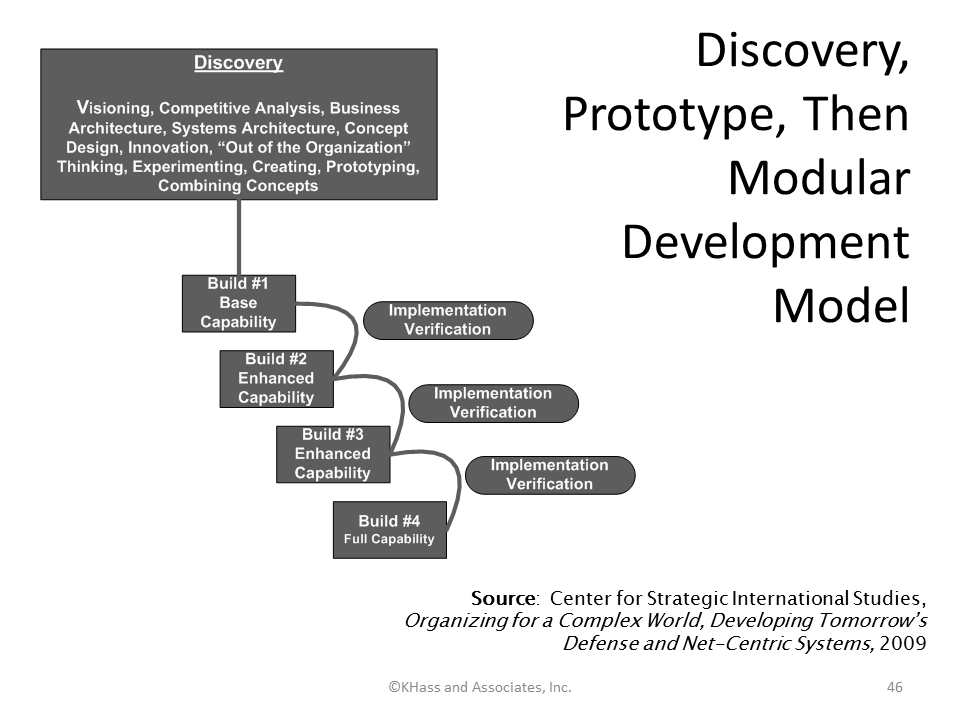

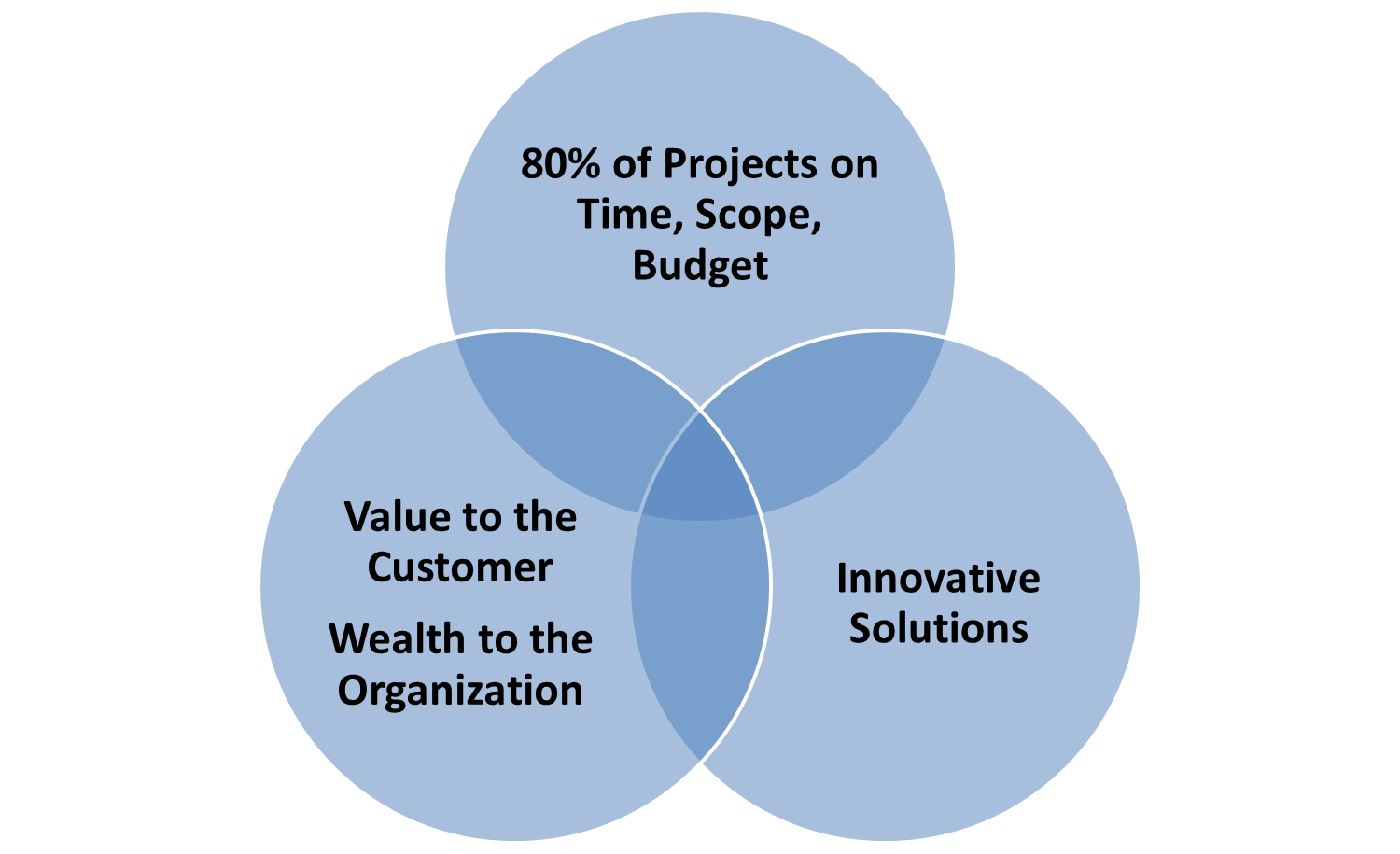

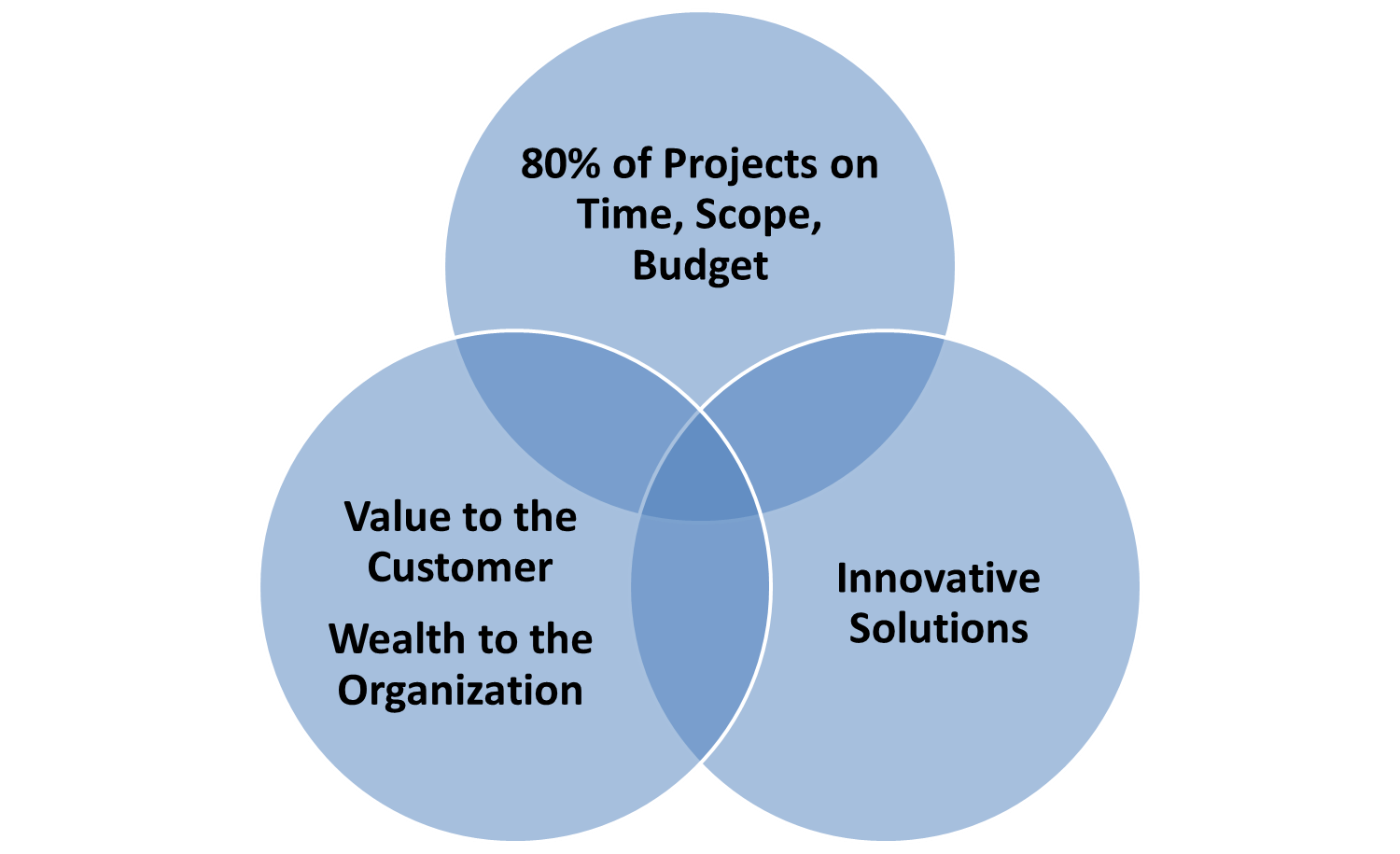

We need to fundamentally change the way we do projects so that 80% of projects are on time, budget and scope (see Figure 1). But we also need to focus on innovative solutions, not incremental changes to business as usual. And we need to bring about value to the customer and wealth to the organization – otherwise, why are we investing in the project? This is where the BA comes in – constantly focusing on value and leveraging complexity to foster creativity.

Figure 1: New Project Approach

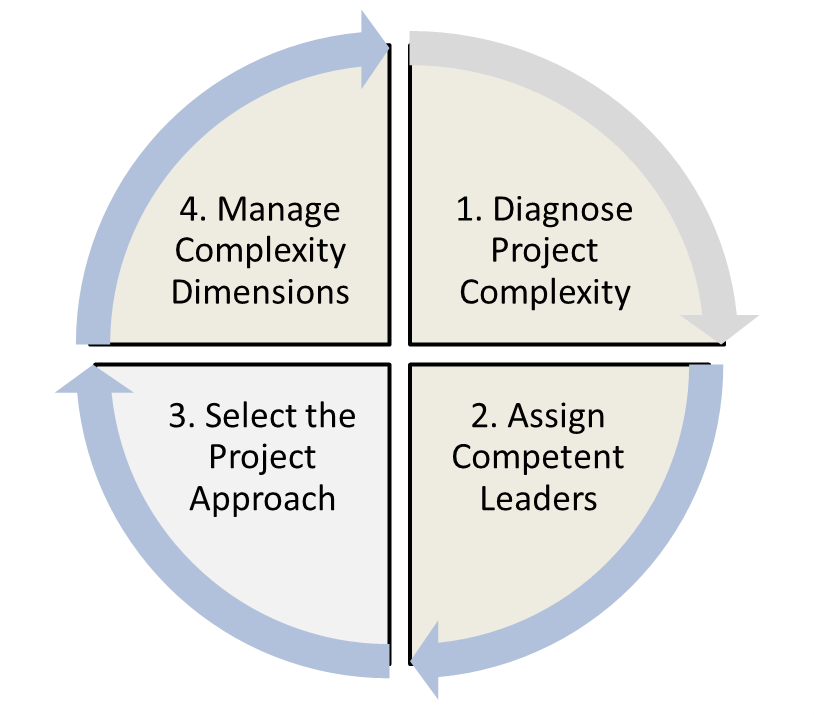

Does the business analyst role change, either significantly or subtly, with highly complex projects? If so, how? Our framework for dealing with complex projects consists of four distinct activities (see Figure 2):

- Diagnose Project Complexity

- Assign Competent Leaders

- Select the appropriate project management approach

- Manage complexity dimensions

This article in the series will examine steps 1 – 3.

Figure 2: Project Complexity Framework

Step #1: Diagnose Project Complexity

The first step in understanding the level of complexity of your project is to assess each complexity dimension. Use the Project Complexity Model depicted in Figure 3. Facilitate your project team leads to agreement on which cells most closely describe your project for each complexity dimension. Then apply the project complexity formula to determine the complexity profile of your project. In my experience, the actual complexity of projects exceeds the team’s initial assessment prior to applying the model.

PROJECT COMPLEXITY MODEL 2.0

|

Complexity Dimensions |

Project Profile |

|||

|

Independent Project |

Moderately Complex Project |

Highly Complex Project |

Highly Complex Program “Megaproject” |

|

|

Size/Time/Cost |

Size: 3–4 team members |

Size: 5–10 team members |

Size: > 10 team members |

Size: Multiple diverse teams |

|

Team Composition and Past Performance |

PM: competent, experienced |

PM: competent, inexperienced |

PM: competent; poor/no experience with complex projects Team: internal and external, have not worked together in past |

PM: competent, poor/no experience with megaprojects |

|

Urgency and Flexibility of Cost, Time, and Scope |

Scope: minimized Milestones: small |

Scope: achievable |

Scope: over-ambitious Milestones: over-ambitious, firm |

Scope: aggressive |

|

Clarity of Problem, Opportunity, Solution |

Objectives: defined and clear Opportunity/Solution: easily understood |

·Objectives: defined, unclear |

Objectives: defined, ambiguous |

Objectives: undefined, uncertain Opportunity/Solution: undefined, groundbreaking, unprecedented |

|

Requirements Volatility and Risk |

Customer Support: strong |

Customer Support: adequate Requirements: understood, unstable |

Customer Support: unknown |

Customer Support: inadequate |

|

Strategic Importance, Political Implications, Stakeholders |

Executive Support: strong |

Executive Support: adequate |

Executive Support: inadequate |

Executive Support: unknown |

|

Level of Change |

Organizational Change: impacts a single business unit, one familiar business process, and one IT system |

Organizational Change: impacts 2–3 familiar business units, processes, and IT systems |

Organizational Change: impacts the enterprise, spans functional groups or agencies; shifts or transforms many business processes and IT systems |

Organizational Change: impacts multiple organizations, states, countries; transformative new venture |

|

Risks, Dependencies, and External Constraints |

Risk Level: low |

Risk Level: moderate |

Risk Level: high External Constraints: key objectives depend on external factors |

Risk Level: very high |

|

Level of IT Complexity |

Technology: technology is proven and well-understood |

Technology: technology is proven but new to the organization |

Technology: technology is likely to be immature, unproven, complex, and provided by outside vendors |

Technology: technology requires groundbreaking innovation and unprecedented engineering accomplishments |

Figure 3: Project Complexity Model 2.0

© Kathleen B. Hass and Associates, Inc.

Then apply the formula below, Figure 4 to diagnose the complexity level of your project.

PROJECT COMPLEXITY FORMULA

|

Highly Complex Program “Megaproject” |

Highly Complex Project |

Moderately Complex |

Independent |

|

Size: Multiple diverse teams, Time: Multi-year, Cost: Multiple Millions Or 2 or more in the Highly Complex Program/Megaproject column |

Organizational Change: impacts the enterprise, spans functional groups or agencies, shifts or transforms many business processes and IT systems Or 3 or more categories in the Highly Complex Project column And No more than 1 category in the Highly Complex Program/Megaproject column |

3 or more categories in the Moderately Complex Project column Or No more than 2 categories in the Highly Complex Project column and |

No more than 2 categories in the Moderately Complex Project column And No categories in the Highly Complex Project or the Highly Complex Program/Megaproject column |

Figure 4: Project Complexity Formula

© Kathleen B. Hass and Associates, Inc.

Step #2: Assign Competent Project Leaders

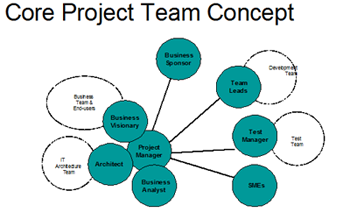

Complex projects require seasoned leaders, and the use of a shared leadership model (see Figure 5). The core project leadership team consists of the PM, BA, Chief Architect, Development Lead and a Business Visionary, each taking the lead when a particular expertise is needed.

Figure 5: Shared Leadership Model

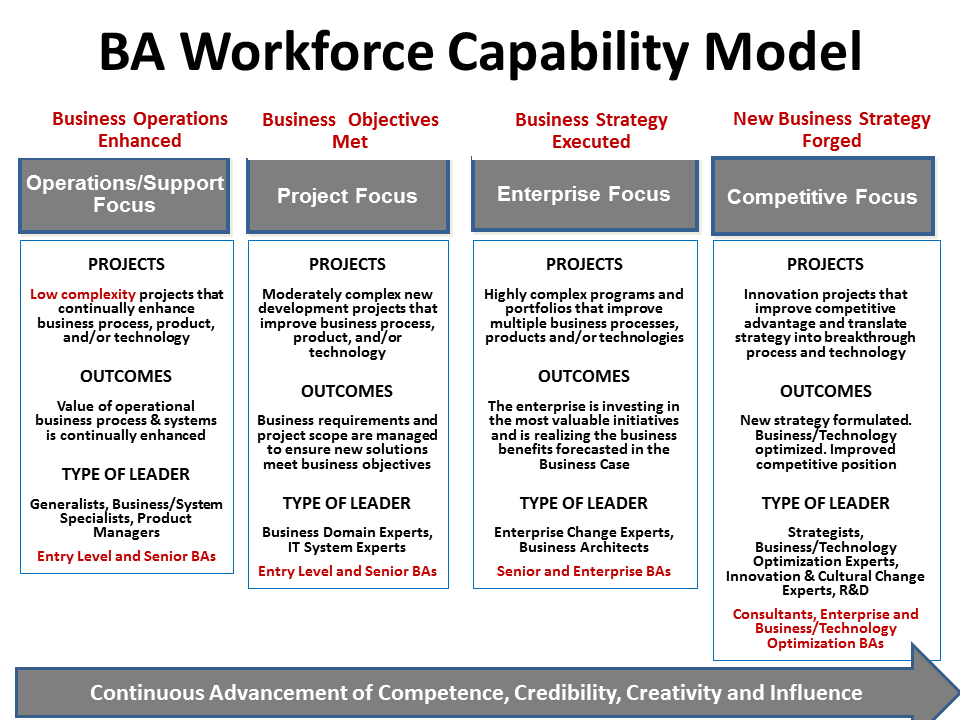

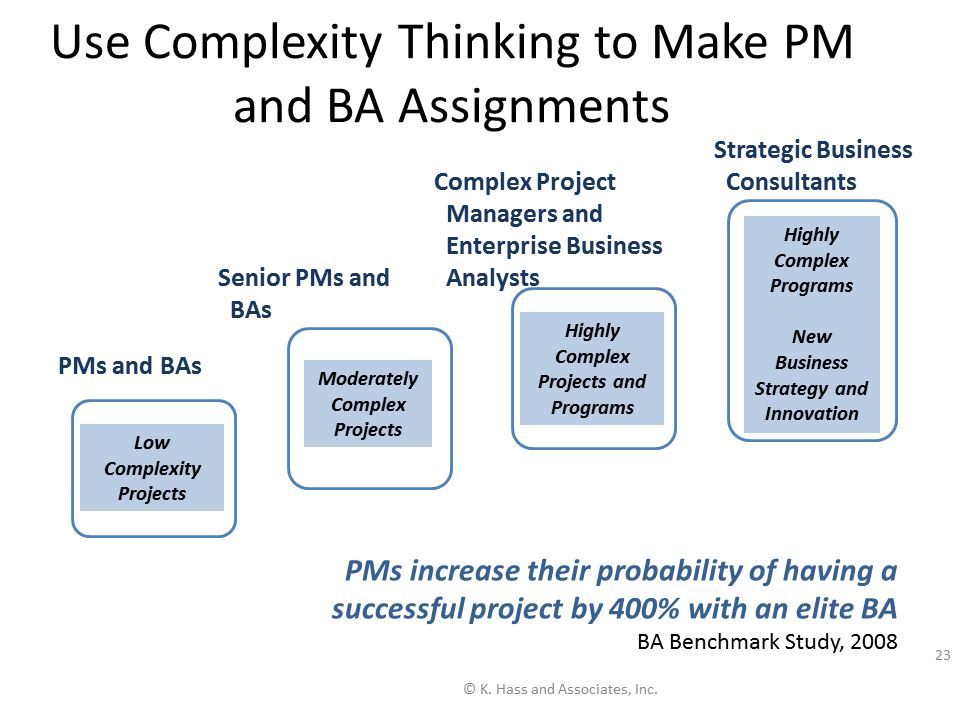

Once the project complexity is known, it is imperative that appropriately skilled and experienced individuals are assigned to key leadership positions. Obviously, BAs need more sophisticated skills as they move from low complexity projects, to enterprise, strategic and innovation projects. The first order of business is for the organization to understand their BA Workforce. Check out the blog site: http://baassessmentmatters.blogspot.com/ posting on March 5th entitled “Calling All BA Practice Leads!” It discusses how BA Practice Leads ensure their organizations have an appropriately skilled BA workforce (see Figure 6) possessing the capabilities needed to successfully deliver complex new business solutions that meet 21st century business needs.

Figure 6: BA Workforce Capability Model

The BA Manager or Practice Lead then assigns BAs (and working with other managers, assigns other project leaders) based on the complexity profile of the project at hand (Figure 7). If the project leads’ capabilities are lower than the complexity of the project requires, it is almost certain that you will have a challenged and/or failed project.

Figure 7: Make Appropriate Leadership Assignments

Step #3: Select the Project Approach

As projects have become more complex, project cycles have evolved. Project cycles models are not interchangeable; one size does not fit all. Project cycles can be categorized into three broad types:

- Linear: used when the business problem, opportunity, and solution are clear, no major changes are expected, and the effort is considered to be routine. A linear cycle is typically used for maintenance, enhancement, and continuous process improvement projects. It is also used for development projects when requirements are well understood and stable, as in shrink-wrap software development projects.

- Adaptive: used when the business problem, opportunity, and solution are unclear and the schedule is aggressive. An adaptive cycle is typically used for new technology development, new product development, or complex business transformation projects.

- Extreme: used when the business objectives are unclear or the solution is undefined. An extreme cycle is typically used for research and development, new technology, and innovation projects.[4]

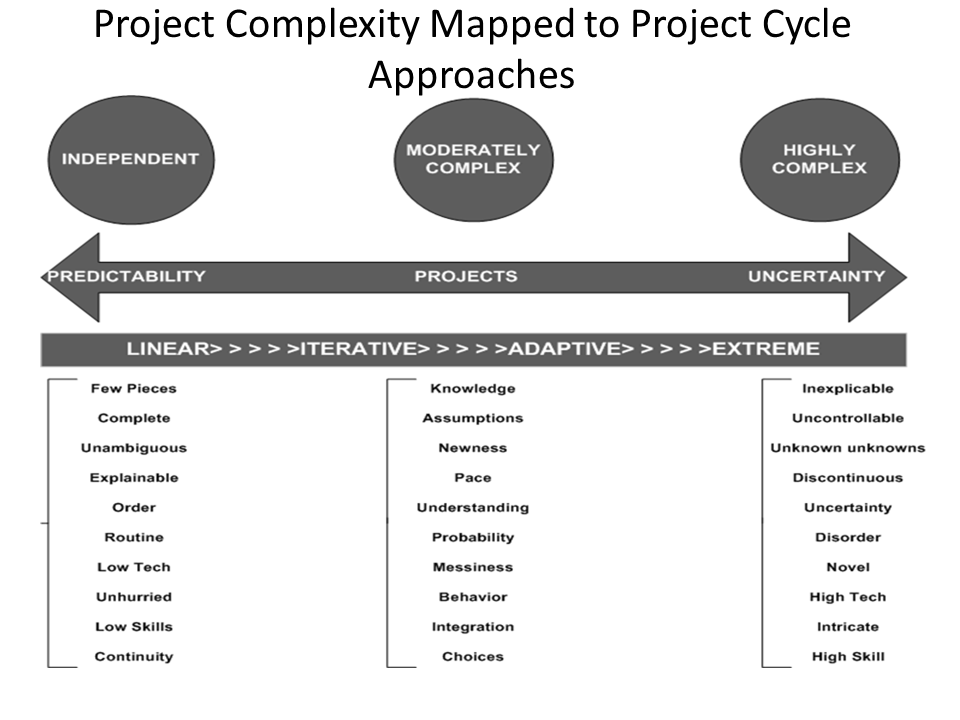

Figure 8 shows the differences between linear and more adaptive methods.

|

Linear Methods |

Adaptive Methods |

|

Figure 8: Linear vs. Adaptive Methods

As we move along the complexity continuum from independent, low complexity predictable projects to highly complex projects with lots of uncertainty, we also move along the spectrum of project cycle types. A linear approach works for a simple, straightforward project; whereas, adaptive, and extreme approaches are used to manage the uncertainties of increasingly complex efforts (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Project Complexity Mapped to Project Cycle Approaches

© Kathleen B. Hass and Associates, Inc.

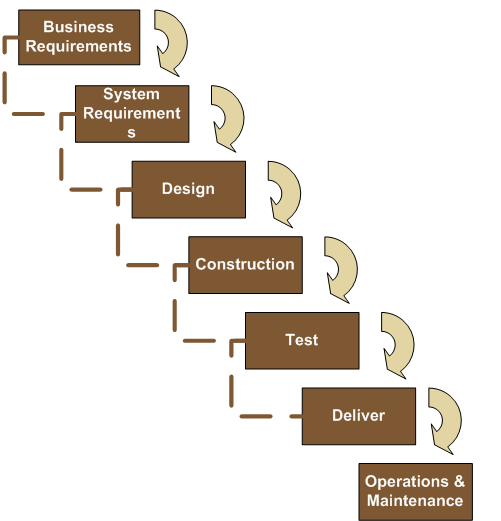

Low-Complexity Projects: Traditional Waterfall Methods

The traditional role of the business analyst does not need to change much to successfully execute activities on low-complexity projects. The linear Waterfall Model is appropriate (see Figure 10). However, to optimize the business analyst role, it is wise to adopt some of the principles of agile and iterative development for even low-complexity endeavors:

- Prototype for requirements understanding, to reduce risk, and to prove a concept

- Involve the business and keep the business analyst as a member of the core project leadership team throughout the project

- Continuously validate, evolve, and improve requirements throughout the project.

Figure 10: The Waterfall Model

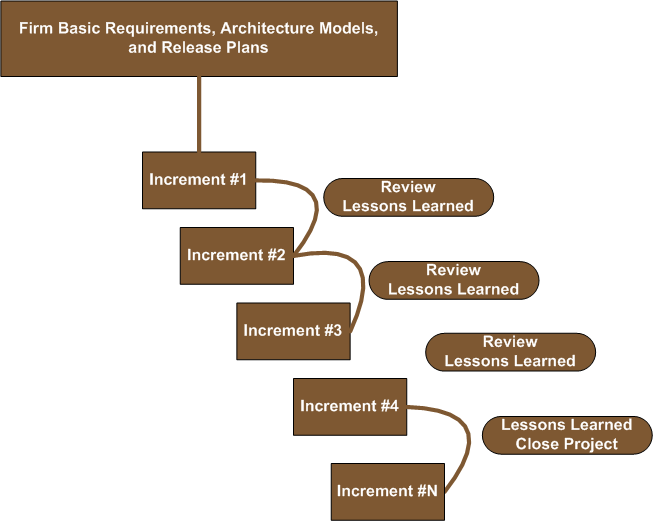

Moderately Complex Projects: Agile Methods

There’s no question about it: agile methods expedite the product development process, especially for products that are software intensive. Agile is an adaptive, streamlined model, based on having only essential people work in tight-knit teams for quick and efficient results (see Figure 11). As we’ve seen, one very important member of the team is the business analyst; if companies hope to achieve strategic goals, they need someone who is focused on the business value expected from the project outcomes. The business analyst provides guidance before funds are invested, during a project, and after the solution is delivered. She continually focuses on the evolving business requirements and serves as the steward of the business benefits.[5]

Figure 11: The Agile Model

Through leadership and collaboration, the project manager and business analyst guide the agile team, ensuring that it is both efficiently and effectively run and that it adds significant long-term benefits for the company with each iteration. The business analyst plays close attention to the original business case, recommending the project be terminated when the ROI has been realized.

Firm Basic Requirements

A business analyst’s main priority when she is first attached to a specific project is to elicit firm, basic business requirements (what we used to call high-level requirements, which outline the breadth of requirements and which we do not expect to change), to collaboratively determine the most feasible solution, and then to categorize releases into valuable features and functions. Then each release is initially described in enough detail to determine its cost versus its benefits, thus developing an ROI for each release.

Knowing what it will take to deliver each individual component of the solution as well as what the return will be to the organization, the development team can then build components or features based on business value, delivering the highest-value features first. As the project moves through the release schedule, the business analyst elaborates the requirements in enough detail to meet the development team’s needs for each release.

An Eye on the Business Value

As an agile project progresses through its life cycle, the team continually learns new information. It becomes clearer how many resources will be needed to perform detailed design, construction, and tests for each release, how much risk there is to the project, and how the risk needs to be managed. Accordingly, it is important to go back and check original assumptions about business value and costs to develop and operate the new solution to see if they are still true, or if the original business case has been compromised.

Validation after Every Release

By being involved during the development process, business analysts can validate that new components are actually meeting business needs and that the business case is still sound. They also take information to other groups outside of the agile team to further corroborate that the inevitable changes have the support of other stakeholders.

Organizational Transition Requirements

The operational environment needs to be analyzed and assessed before the solution components are implemented. Perhaps there will be a need for reorganization, retooling, retraining, or acquisition of new staff. Working with management, the business analyst helps to ensure the organization is prepared for the impact of the changes and can support the release plan. That way, when the complete solution is delivered, it can be operated efficiently and effectively.

Lighter Requirements

Agile requirements are typically “lighter” than those developed for linear project models. Requirements are visually documented whenever possible. The wise business analyst uses modeling to manage complexity. Less formal user stories (a high-level description of solution behavior) may suffice, as opposed to use cases.

Advanced Skills

Advanced skill development is required for business analysts who are working on agile projects. They need to develop new or higher-level leadership skills, including expert facilitation, coaching, collaborative decision-making, and team development. The analyst also needs to have a good understanding of software architecture and be proficient in decoupling the breadth of the solution from the depth of the solution into feature-driven requirements.

Highly Complex Projects, Programs, and Megaprojects: Extreme Methods

Welcome a certain amount of complexity and churn because it creates a chemical reaction that jars creative thinking.

—Colleen Young, VP and distinguished analyst and IT adviser, Gartner, Inc.

Highly complex projects offer the greatest opportunities for creativity: complexity breeds creativity. But the business analyst must understand the nature of complexity to leverage complexity to foster innovation. Complexity is one of those words that is difficult to define. Some say complexity is the opposite of simplicity; others say complicated is the opposite of simple, while complex is the opposite of independent.

Since complex projects are by their very nature unpredictable, it is imperative that the project team keep its options open as long as possible, building those options into the project approach. This approach requires that considerable time be dedicated to researching and studying the business problem or opportunity; conducting competitive, technological, and benchmark studies; defining dependencies and interrelationships; and identifying potential options to meet the business need or solve the business problem. In addition, the team experiments with alternative solutions and analyzes the economic, technical, operational, cultural, and legal feasibility of each option until it becomes clear which solution option has the highest probability of success. When the opportunity is unclear and the solution is unknown, traditional linear approaches simply will not work.

Last-Responsible-Moment Design Decisions

On highly complex projects, it is important to separate design from construction. The key is to use expert resources and allow them to spend enough time experimenting before they make design decisions; the construction activities will thereby become much more predictable. Linear methods might then be appropriate during the construction phase of the project.

Models for adaptive project management are still emerging. We suggest two that are designed to provide iterative learning experiences, adapt and evolve as more is learned, allow analysis and experimentation to determine solution design viability, and delay decision-making as long as possible (that is, until the last responsible moment, the point at which further delays will put the project at risk): the adaptive evolutionary prototyping model and the eXtreme project management model. There are significant differences between the adaptive and eXtreme approaches (see Figure 12).

|

Adaptive Methods |

eXtreme Methods |

|

· Keep your options open ◦ Build options into the approach · Discover, experiment, create, innovate ◦ Analyze problem/opportunity ◦ Conduct competitive, technical, and benchmark studies ◦ Brainstorm to identify all possible solutions ◦ Analyze feasibility of each option ◦ Design and test multiple solutions |

Figure 12: Adaptive vs. Extreme Methods

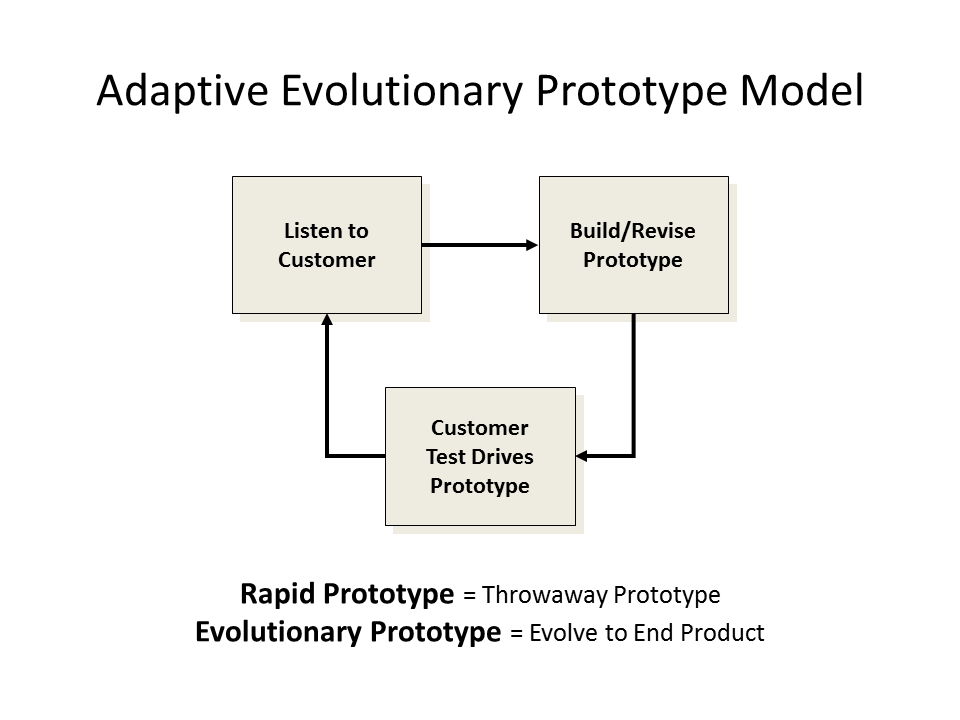

Evolutionary Prototyping Model

The keep-our-options-open approach often involves rapid prototyping—a fast build of a solution component to prove that an idea is feasible—which is typically used for high-risk components, requirements understanding, or proof of a concept.

Evolutionary prototyping is quite effective for multiple iterations of requirements elicitation, analysis, and solution design. Iteration is the best defense against uncertainty because with each iteration, the technical and business experts examine the prototype and glean more information and certainty about functions that are built into the next iteration.

The strength of prototyping is that customers work closely with the project team, providing feedback on each iteration (see Figure 13). If requirements are unclear and highly volatile, prototyping helps bring the business need into view.

.

Figure 13: Adaptive Evolutionary Prototype Model

© Kathleen B. Hass and Associates, Inc.

eXtreme Project Management Model

An extreme project is a complex, high-speed, self-correcting venture during which people interact in search of a desirable result under conditions of high uncertainty, high change, and high stress.

—Doug DeCarlo, author and lecturer,

Extreme Project Management

eXtreme project management is sometimes also called radical project management. Some equate it to scaled-up agile methods. The approach consists of a number of short, experimental iterations designed to determine project goals and identify the most viable solution. As in the agile model, eXtreme project management requires that the customer be involved every step of the way until the solution emerges—a practice that involves many iterations. Like the iterative Spiral Model, the eXtreme model terminates after the solution is found (or when the sponsor is unwilling to fund any more research); the project team then transitions to one of the other appropriate models. One variation of the eXtreme Model spends a considerable amount of time in discovery, then prototypes, then transitions to modular development (see Figure 14).

Figure 14: eXtreme Model

© Kathleen B. Hass and Associates, Inc.

Challenges will arise at every turn, because it can be difficult to:

- Know how long to keep your options open

- Build options into the approach without undue cost and time

- Gather the right group of experts to discover, experiment, create, innovate, and:

◦ Analyze the problem/opportunity

◦ Conduct competitive, technical, and benchmark studies

◦ Brainstorm to identify all possible solutions

◦ Analyze the feasibility of each option

◦ Design and test multiple solutions.

Operating on the Edge of Chaos

Conventional business analysis practices that assume a stable and predictable environment encourage us to develop all the requirements up front, get them approved, and then fiercely control changes. As we have seen, conventional linear project cycles work well and should be used for predictable, repeatable projects; however, this approach has proven to be no match for chaotic 21st-century projects. Figure 15 compares the characteristics of projects on which conventional linear practices can be successfully used with the characteristics of projects that require a more adaptive model. A blend of the linear, adaptive, and eXtreme models is almost always the answer. The trick is to know when and how to apply which approach.

|

Conventional linear approaches work well for projects that… |

Adaptive approaches work well for projects that… |

|

Are structured, orderly, disciplined |

Are spontaneous, disorganized |

|

Rely heavily on plans |

Evolve as more information is known |

|

Are predictable, well defined, repeatable |

Are surprising, ambiguous, unique, unstable, innovative, creative |

|

Are built in an unwavering environment |

Are built in a volatile and chaotic environment |

|

Use proven technologies |

Use unproven technologies |

|

Have a realistic schedule |

Have an aggressive schedule; there is an urgent need |

Figure 15: Conventional vs. Adaptive Approaches

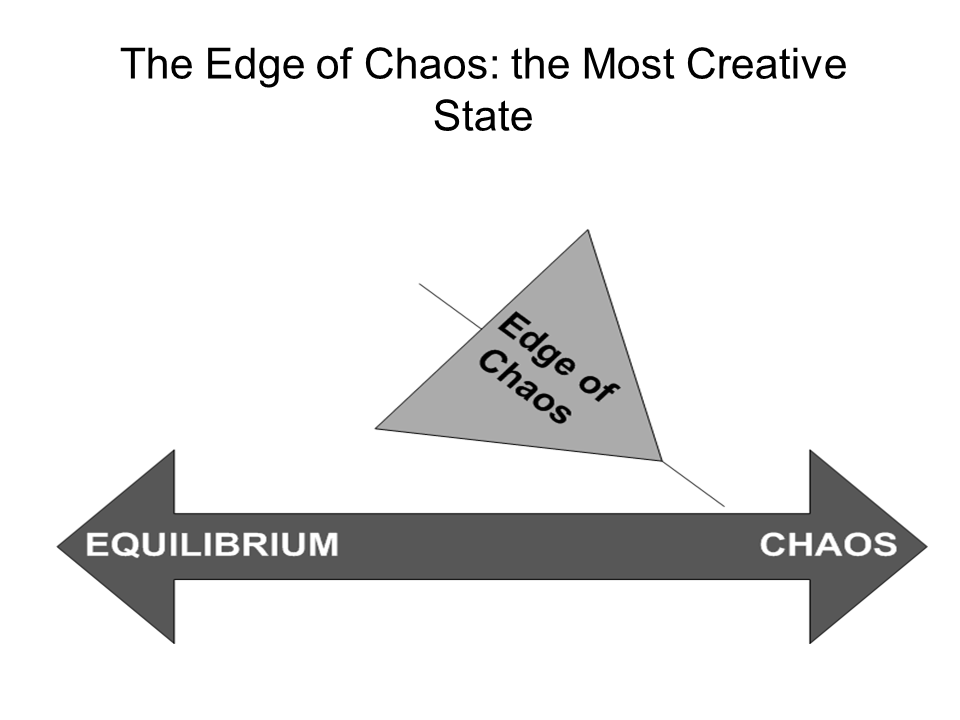

What exactly does it mean to operate on the edge of chaos? Complex systems fluctuate between a static state of equilibrium and an adaptive state of chaos. If a system remains static, it will eventually result in paralysis and death. Whereas, if a complex system is in chaos, it is unable to function. So, here is the genius of complexity: it breeds and nourishes creativity, as complex systems adapt to changes in the environment for survival. Complexity scientists tell us that the most creative and productive state is at the edge of chaos. (Refer to figure 16.) Therefore, complex project teams must operate at the edge of chaos for a time in order to allow the creative process to flourish. The business analyst assigned to a complex project must use adaptive business analysis methods to foster an environment where creativity is possible. The next article in this series explores the business analyst as creative leader of complex projects who are living on the edge.

Figure 16: The Edge of Chaos: the Most Creative State

Putting It All Together: What Does This Mean to the Business Analyst?

A business analyst who is an asset to highly complex projects is comfortable with lots of uncertainty and ambiguity in the early stages of a project. She leads and directs plenty of sessions of brainstorming, alternative analysis, experimentation, prototyping, out-of-the-box thinking, and trial and error, and encourages the team to keep options open until they have identified an innovative solution that will allow the organization to leap ahead of the competition. The BA who does not embrace complexity does so at her own peril.

|

The articles in this series are adapted with permission from The Enterprise Business Analyst: Developing Creative Solutions to Complex Business Problems by Kathleen B. Hass, PMP. © 2011 by Management Concepts, Inc. All rights reserved. The Enterprise Business Analyst: Developing Creative Solutions to Complex Business Problems |

|

|

About the Author Kathleen B. (Kitty) Hass, PMP Senior Practice Consultant Kathleen Hass & Associates, Inc. Email: [email protected] Website: www.kathleenhass.com Blog: http://baassessmentmatters.blogspot.com/ Twitter: @ BA_Assessment @KathleenHass1 |

Kitty is the president of her consulting practice specializing in enterprise business analysis, complex project management, and strategy execution. She is a prominent presenter at industry conferences, author and facilitator. Her BA Assessment Practice is the gold standard in the industry. KHass BA Assessments:

- Appraise both BA organizational maturity and individual/workforce BA capability based on four-stage reference models

- Present results that are continuously examined for reliability and validity by Lori Lindbergh, PhD, Senior Researcher and Psychometrician , Lorius, llc

- Benchmark results against a global data base of BAs performing comparable work

- Align with the IIBA BABOK® and the BA Competency Model®

- Align with standards and best practices for quality and fairness in educational and psychological assessment

- Are based on the skills and knowledge needed to work successfully on the complexity of current project assignments

- Examine critical relationships between competency, project complexity, and project outcomes.

In addition to assessments, Kitty’s expertise includes implementing and managing PMOs and BACOEs. She has over 25 years of experience providing professional services to Federal agencies, the intelligence community, and Fortune 500 companies. Kitty is a Director on the IIBA Board and Chair of the IIBA Board Nominations Committee. She has also authored numerous white papers and articles on leading-edge business practices, the renowned series entitled, Business Analysis Essential Library, and the PMI Book of the Year, Managing Project Complexity – A New Model.

[1] Tom Friedman, Michael Mandelbaum, That Used to be us: How America Fell Behind in the World it Invented and How we can Come Back, 2011.

, The New York Times, January 21, 2012. Online at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/business/apple-america-and-a-squeezed-middle-class.html?pagewanted=4&ref=charlesduhigg

Figure 11: The Agile Model

Figure 11: The Agile Model .

.