Why Agile isn’t Enough Part 2: Lean Startup Build Phase and BA Techniques that Enhance it

In part 1 of this article, we covered an overview of Lean Startups and its Build-Measure-Learn (B-M-L) methodology.

To recap, in the B-M-L cycle we build a product increment, measure how it is adopted and used, and learn from the measures about what worked and didn’t and use it for the next cycle.

In this part we’ll examine the Build part of the cycle in more depth and see which Business Analysis techniques are most helpful to propel the Lean Startup to providing innovation and value. Part 3 will cover the remaining two parts, Measure and Learn.

BUILD

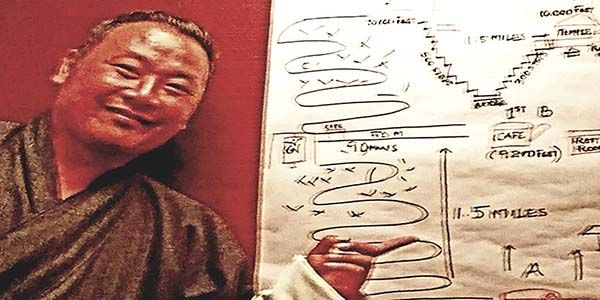

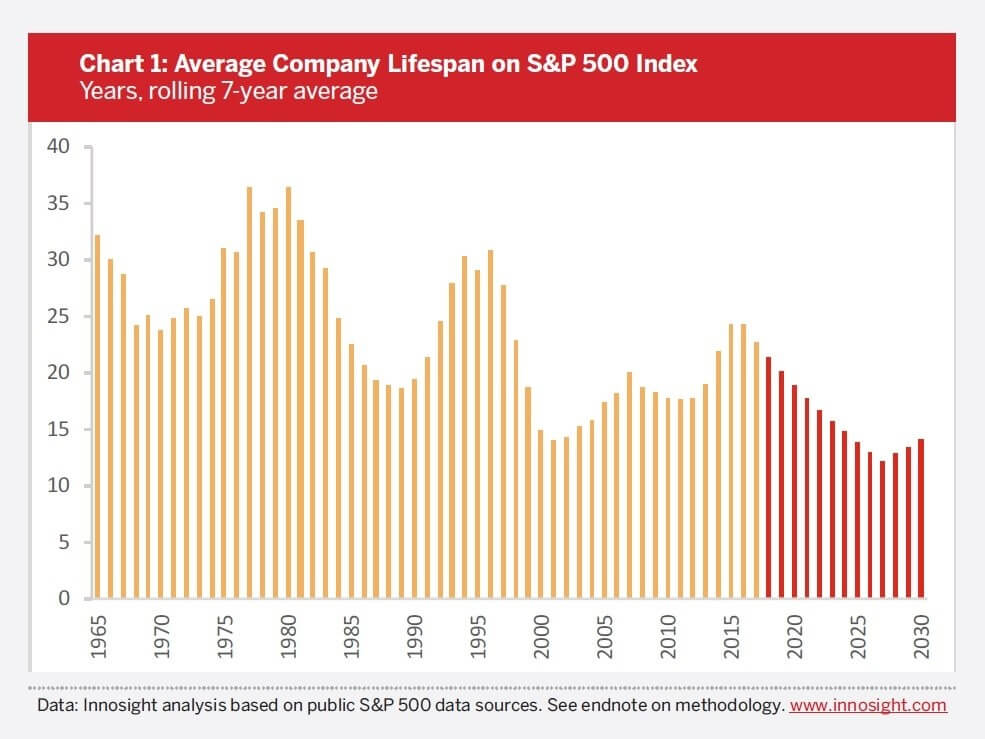

To review, the Build-Measure-Learn methodology within Lean Startup is the central engine driving the process. Lean Startups rely on repetitive cycles of B-M-L to produce various product increments as recapped in Figure 1. An important milestone while building a product is to reach a Minimum Viable Product or MVP such as in “P2” below.

MVP

The concept of a Minimum Viable Product was popularized by Eric Ries in The Lean Startup1 and has been genericized quite a bit in our industry. In Lean Startup an MVP is the product produced with the minimum effort and the quickest path or paths through the B-M-L loop. Product P2 in Figure 1 shows an MVP produced after two times through the loop.

Figure 1: Lean Startup Framework

More than a prototype or proof of concept, the goal of an MVP is to test fundamental business hypotheses about a product. For example, the hypothesis of whether customers would pay to have DVDs shipped to them and return them by mail was the basis of Netflix.

Another way to think of an MVP is “a first attempt at building a solution to a problem worth solving.” The learning starts with testing the fundamental hypothesis and continues with each new feature added. We’ll return to learning in part 3.

Take the video communication app called Marco Polo. This app allows family and friends to communicate by directly sending videos right from the app. That’s basically all the app does, but I can tell you our family is totally addicted to it! It is valuable to us since we live in cities across the US and can hear and see what family members are doing. It’s incredibly valuable to us since our kids and grandkids keep us updated much more often with it than by phone or email.

Marco Polo is now a bit beyond an MVP as of this writing, but not much. The initial MVP just let users record and play videos and was enough for their startup to learn from. They added the ability to Fast Forward and Rewind based on user feedback. They also added a few other features, but it is still fairly basic as of this writing. Without a Lean Startup mentality, though, adding additional potential features would have delayed their launch and may not be widely used.

MVP: “A first attempt at building a solution to a problem worth solving.” Eric Ries

Leap of Faith

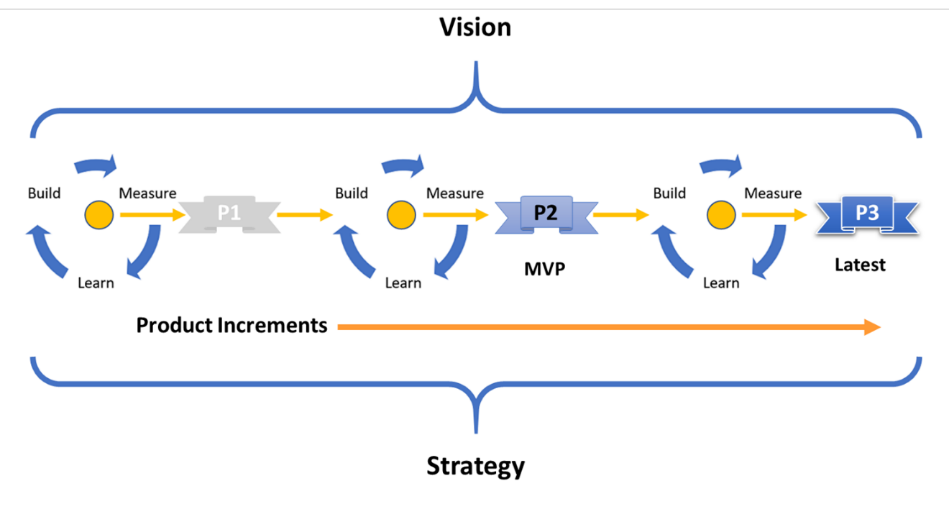

All startups are based on assumptions and get started as a “leap of faith.” It’s the basic hypothesis of a new product or company. There is a paradox here, though: we aim to ultimately build things for the “masses”(see Figure 2) but need to start with the early adopters or our product likely won’t get off the ground.

Figure 2: Product Adoption Over Time

It’s important to know and note the assumptions that form the “leap of faith.” Business Analysis skills can help by ferreting out and documenting those assumptions. As we do that, it’s important to avoid false analogies that obscure the “true leap of faith.” Eric Ries in The Lean Startup suggests we shun borrowed analogies like “this worked for Apple so it will work for us.”

Speaking of Apple, their Apple Watch was a leap of faith whether people were willing to read texts or listen to music on their watches, which many did want and still do.

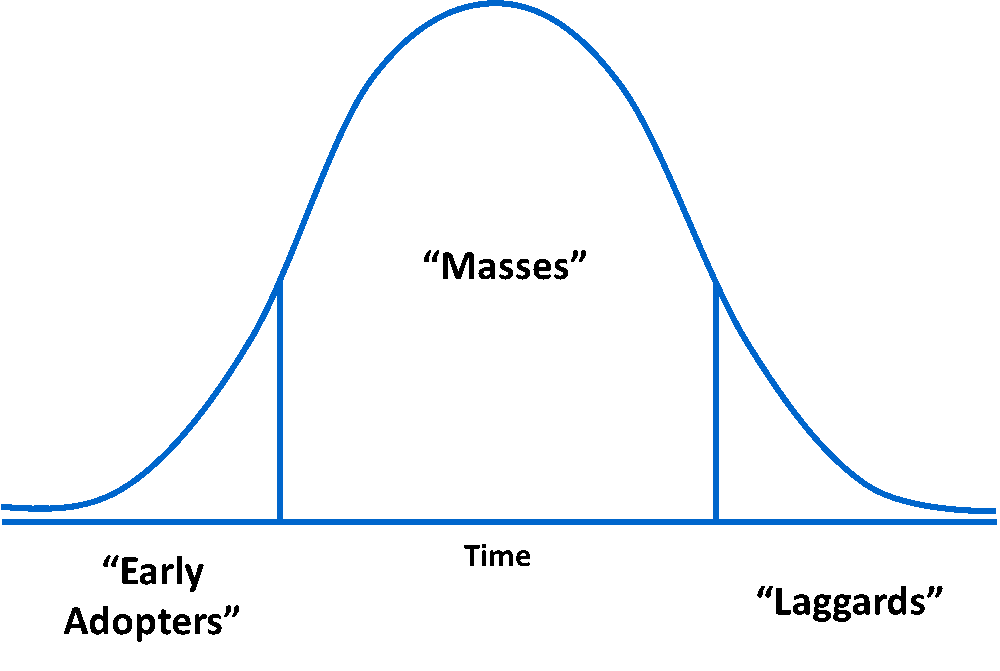

Build – 13 techniques

Figure 3 lists the BA techniques for the Build phase. Looking through the list, which techniques have you found to be the most helpful in developing new products? If I was on a desert island and could only use 5 techniques, I’d have to say Benchmarking, Brainstorming, Lean Canvas, Observation, and Prototyping would be my choices. The details and applications of the techniques are beyond the scope of this article but are intended to be a reference.

Figure 3: Techniques Useful in the Build Stage

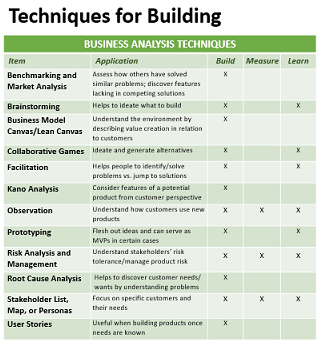

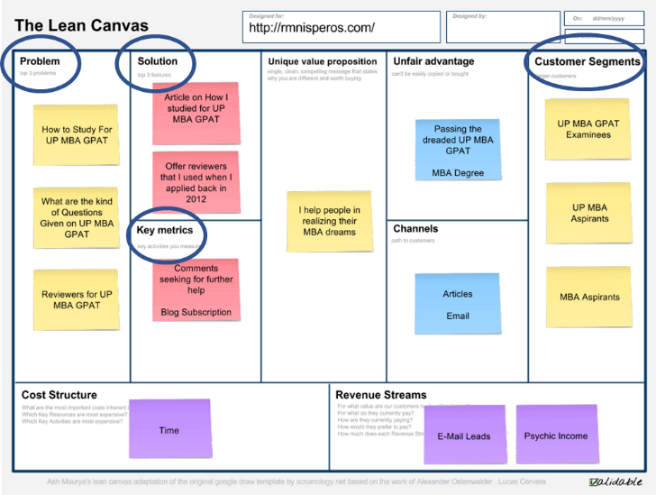

The Business Model Canvas is becoming more and more popular and for good reason. But it is meant more for established business and doesn’t help as much as a newer technique called the “Lean Canvas.” The Lean Canvas tool helps focus on customers and their solutions based on need. See Figure 4 for an example. Like the Business Model Canvas the Lean Canvas has nine categories to help spur thinking and help create a product of value.

I particularly like the first two categories, “Problem” and “Solution,” since they focus on two of the most critical aspects of delivering a valuable solution. I also like including “Key Metrics” in the middle and we’ll discuss metrics in Part 3. The upper right-hand section labeled “Customer Segments” is also a key factor since it focuses on the customer and possible segments or “cohorts” of users.

Figure 4: Lean Canvas Example

Customer Segments is also valuable since we have found as entrepreneurs it is critical to first find customers in need and then build or deliver solutions that will appeal to them. It is much riskier and potentially wasteful to build products and then find customers we think will need them. Take the example of Teforia, who built a “tea-infusion system” that sold for up to $1,300 per machine. As it turned out, people weren’t willing to pay that much for tea so the product was a failure (and the startup folded).

Summary

In summary, the Build portion of the Lean Startup methodology leads off the cycle. It relies on vision and ideas for solving a problem at first. It then uses learning from product measures to adjust the product with new or changed features in future cycles. The final part of this article will explore the latter two portions, Measure and Learn, in more detail.