How AI will Affect Business Analysis in 2024

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been making waves in the field of technology, and experts firmly believe that it will continue to grow in 2024. AI has become an integral part of our daily lives, manifesting through voice assistants for customer service, chatbots, market trend prediction, proactive identification of potential health issues, and other such things. In recent times, businesses have increasingly embraced AI to enhance their efficiency and secure a competitive advantage. That is why the importance of artificial intelligence is being taught in business analyst courses.

AI is transforming the business landscape, playing a pivotal role in boosting growth and operational efficiency. It has evolved into a formidable ally, assisting businesses to get data-driven insights, optimize processes, and enhance decision-making capabilities. Once a blurry science fiction vision, AI has become a necessity for modern businesses. Its journey from just a theoretical groundwork in the mid-20th century to corporate boardrooms in 2024 has been astonishing. But how will it affect business analysis and the jobs of professionals in the future?

Well it is reported by Goldman Sachs that Ai could potentially replace 300 million full time jobs world wide.

The good news is Business Analysis as a job cannot be replaced with Ai, but the job can be supplemented with Ai.

The reason for this is, business analysts help organizations effectively implement change initiatives, the biggest change since the emergence of the internet has been the use of Ai, which is set to disrupt many markets. In order for organisations to stay competitive, organisations will have to implement the changes to their processes and embed the wave of Ai, and which role in particular helps organisations implement change? Business Analysts!

Let’s now delve into AI’s role in business analysis and how things will unfold.

Enhanced Data Analysis

AI is capable of processing complex data in large volumes and at a high speed. This will lead to more accurate business insights in less time. AI-powered text analytics tools can quickly analyze unstructured data like social media comments or customer reviews, which will provide valuable insights into customer preferences and sentiment. This allows businesses to make more informed decisions, increasing productivity.

Predictive Analytics

The adoption of AI for predictive analytics is now widespread in the realm of business intelligence. Companies, both large and small, are leveraging AI models to swiftly analyze various data sets, such as sales, customer information, and marketing data. This utilization of AI empowers businesses to proactively anticipate market trends, understand customer behaviors, and identify potential risks.

While predictive analytics has been a part of business strategies for as long as data has been collected, the integration of AI has revolutionized the process. This foresight becomes instrumental in guiding strategic decisions and enhancing the overall efficiency of business analysis procedures.

Automation of Routine Tasks

AI is poised to automate routine and repetitive tasks in business analysis, thereby reducing errors, enhancing efficiency, and liberating human resources. This, in turn, enables business analysts to concentrate on more intricate and strategic facets of their work. The automated tasks encompass processes like data collection and report generation, which, when handled by AI, release valuable time for value-added analysis.

Natural Language Processing (NLP)

AI-powered NLP will allow business analysts to interact with data using natural language. It means that users with business analyst certification as well as non-technical users will find it easier to understand and access complex datasets. This will lead to collaboration between different departments within an organization.

Personalized Business Insights

AI will allow the customization of business insights based on individual user needs. Analysts can receive tailored recommendations and reports, improving the relevance and applicability of the information provided. AI facilitates a highly personalized customer experience by sifting through customer data in large volumes, including purchase history, browsing patterns, and social media behavior. This capacity for thorough analysis helps businesses recognize individual customer preferences, thus tailoring their interactions and recommendations to cater to these specific tastes and requirements.

Improved Decision Support Systems

AI-driven decision support systems are likely to have a great impact and become integral to business analysis. These systems can process large volumes of data, assess various scenarios, and recommend optimal decisions. This will provide valuable guidance to business analysts and decision-makers.

Real-time Analytics

AI will enhance business analysis through real-time analytics capabilities. By leveraging AI technologies, businesses can access the most up-to-date information, empowering them to make informed decisions promptly. The significance of this real-time capability cannot be overstated, especially in the dynamic landscape of market changes. With AI-driven real-time analytics, businesses can respond swiftly to emerging trends, evolving customer behaviors, and market fluctuations, thereby staying competitive in today’s fast-paced business environment. This proactive approach to data analysis ensures that businesses are not only informed but also well-positioned to adapt and thrive in the face of constant change.

Advertisement

Advanced Pattern Recognition

AI’s advanced pattern recognition capabilities will enhance the detection of subtle trends and anomalies in data. This can be especially valuable in identifying emerging opportunities or potential risks that might go unnoticed with traditional analysis methods. Whether you have completed your business analyst training or not, the AI can make your task a lot easier and accurate.

Improve Risk Management & Fraud Detection

AI algorithms are designed in such a way that they can autonomously interpret and analyze even the most complex financial data. This allows them to uncover hidden patterns and irregularities that might indicate fraudulent activity. By leveraging natural language processing, data analytics, and machine learning techniques, AI systems can process large volumes of structured and unstructured data, find outliers, and generate actionable insights quickly. This approach empowers businesses, and financial institutions in particular, to detect fraudulent activities early and implement appropriate strategies to minimize the risk.

AI for Business Analyst in 2024: A Great Tool, Not a Replacement

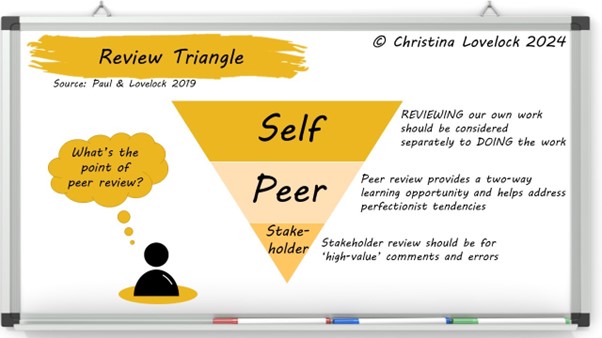

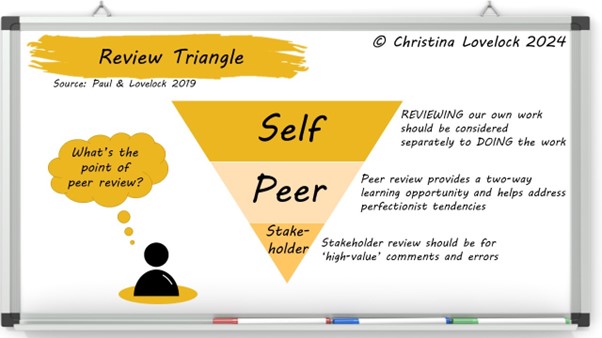

The notion of AI making business analysts obsolete looks unlikely when considering the unique value that these professionals bring to organizations, a dimension that artificial intelligence struggles to replicate. Business analysts play a pivotal role in eliciting, prioritizing, and refining requirements in collaboration with stakeholders—a task that involves nuanced understanding and interpersonal skills that AI currently lacks.

Furthermore, business analysts serve as a crucial bridge between the business and its IT team, ensuring seamless communication and alignment of objectives. Their ability to communicate effectively with stakeholders is not only about conveying information but also about fostering relationships and steering projects towards their goals. This human touch is indispensable in complex organizational dynamics.

The proficiency of business analysts in understanding the end-to-end processes that they learn during business analyst programs, is a multifaceted skill that AI has yet to master. This involves a deep comprehension of organizational intricacies and the ability to navigate the complexities of both the business and technology realms.

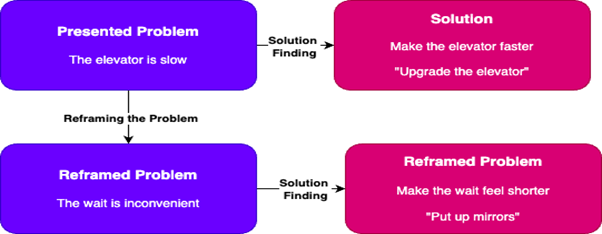

Equally significant is the creative problem-solving approach that business analysts bring to the table. While AI excels in data-driven tasks and pattern recognition, the intuitive and creative thinking required for innovative problem-solving is a distinctively human trait that currently eludes artificial intelligence.

In short, the multifaceted roles and responsibilities of business analysts, encompassing collaboration, communication, understanding of business processes, and creative problem-solving, collectively form a skill set that AI, in its current state, cannot replicate. The symbiotic relationship between AI and human professionals, where each leverages its unique strengths, is likely to persist, ensuring the continued relevance and indispensability of business analysts in the foreseeable future.

Take Away

The profound impact of AI on business analysis is evident. The integration of AI technologies is revolutionizing the industry by automating routine tasks, enabling real-time analytics, and providing customized insights. This transformative shift not only enhances efficiency but also empowers business analysts to delve into more strategic aspects of their work.

The ability of AI to adapt to market changes swiftly ensures businesses remain competitive in the ever-evolving market. The use of AI in business analysis promises not just data-driven decision-making but a major change in how organizations leverage information for growth and innovation. The journey into the future of business analysis is undeniably shaped by the capabilities AI brings to the table.