What’s The Point of Peer Review?

When time is tight and the pressure is on, it feels like ‘peer’ review is a luxury we cannot afford, but what’s the cost of this decision?

What Is Peer Review?

Sharing our analysis outputs (whether this is documents, models, presentation slides or feature tickets) with other business analysts before they are shared with any other stakeholders is the essence of peer review. BA peer reviewers should be able to share useful observations and insights about the output, whether or not they have specific business domain knowledge. If something is not clear to a fellow BA, there is a good chance it will not be understood by customers, suppliers, stakeholders and other recipients.

Why is Peer Review Valuable?

Many business analysts have a tendency towards perfectionism, and the longer we work on something without feedback, the more disappointing it is to receive any feedback, however constructive. It is much harder to accept and incorporate feedback on a polished final draft than an early rough draft. We need to share our work early in the process to be able to influence our own thinking and approach, and prevent us making significant errors or omissions.

Why is Peer Review Valuable?

Peer review is valuable from multiple perspectives.

#1 The producer

The person who created the output. We all bring assumptions to our work, whether this is a single piece of acceptance criteria, complex model or large document. The producer gets the benefits of a fresh perspective and the opportunity to catch errors and drive out assumptions. A peer review should be a way to improve quality without any worry of reputational or relationship risk. It also provides the opportunity for increased consistency across BA products and to learn lessons from other business areas.

#2 The peer reviewer

There is always something to gain from seeing how someone else works, whether they have more or less experience than us, and wherever they sit in the organisational hierarchy. So as well as making a valuable contribution to our colleague’s work we are likely to learn something through peer reviewing.

#3 Stakeholders

Any business, dev team or project stakeholders that will also be asked to review/validate/approve the deliverable will benefit greatly if a peer review has already taken place. Some errors and ambiguities will have been addressed, saving them time and increasing their confidence in the quality of the output.

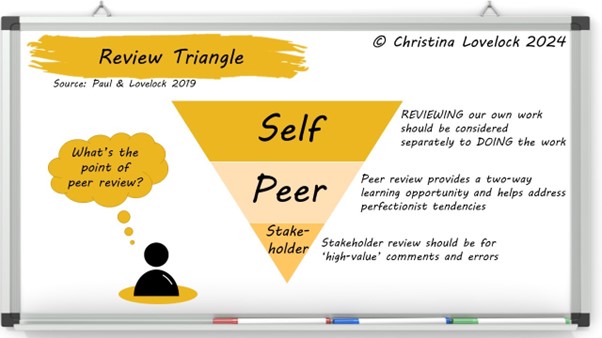

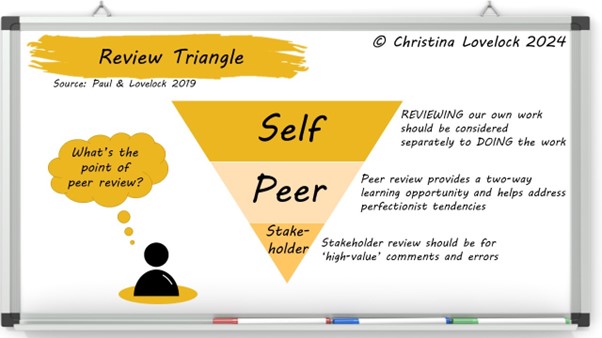

The Review Triangle

This model reminds us that the highest number of errors should be spotted and rectified by the person creating the output, as part of a specific review phase.

Advertisement

Self-Review

The model emphasises the need for self-review, which is a separate activity to creating the analysis output, and involves:

- Standards check (adherences to templates, branding and guidelines)

- Assumptions check (provide key, glossary etc.)

- Accessibility check (e.g. readability, compatibility with assistive tech, alt text for pictures)

- Sense check

- Error check

- Spelling and grammar check.

Moving from a ‘creating’ to ‘reviewing’ mindset can be achieved by taking a break, and switching to reviewing when we return, or moving to a different device as this often forces us to look at something differently.

Peer Review

Peer review is also about adherence to standards, and is valuable even when the reviewer does not have relevant subject matter knowledge. They should be able to identify and challenge assumptions made, spot logic knots and highlight the use of acronyms and jargon. They can also share insights and observations from their own experience, such as level of detail and formats preferred by different internal audiences.

Stakeholder Review

Stakeholders should not be faced with errors that we could have easily caught through self or peer review. This does not mean we should only share perfect and complete outputs, but that we give stakeholders the best chance of spotting significant gaps and fundamental errors by removing low level distractions.

Many stakeholders find it difficult to simply ‘ignore’ spelling and other small errors. This level of error can undermine their confidence in our analysis.

Depending on the number of stakeholders and the complexity of the output, it is often better to do a group review exercise (synchronous) rather than a comments based (asynchronous) review. This is for several reasons:

- Confidence everyone has actually seen what is being reviewed/validated/agreed

- Prevents multiple stakeholders making the same (or conflicting) observations

- Changes can be discussed and agreed.

Conclusion

The benefits of peer review, to individual BAs, the internal BA community and to our stakeholders and customers is significant. Attempting to ‘save time’ by avoiding this activity is a false economy. Organisations that aspire to be a truly ‘learning organisation’ encourage and enable effective peer reviews. Where organisations don’t place emphasis on this, BAs can choose to role model this commitment to quality and learning, and lead by example.

Further reading

Delivering Business Analysis: The BA Service Handbook, D Paul & C Lovelock, 2019