Data Science: Critical role of a Business Analyst

The last decade has witnessed a sudden spurt in vast amount of data, which enterprises possess, on their customers.

This data is generated from disparate sources like social media, mobile, applications, financial transactions, e-commerce, search and Internet of Things etc. According to an IDC estimate, from 2005 to 2020, the digital universe will grow by a factor of 300, from 130 exabytes to 40,000 exabytes, or 40 trillion gigabytes. From now until 2020, the digital universe will about double every two years. Further, IDC estimates that only a tiny fraction of the digital universe has been explored for analytic value. By 2020, as much as 33% of the digital universe will contain information that might be valuable if analyzed.

Previously, companies were able to analyze relatively smaller set of data through various data mining techniques and tools. However, with the data exploding from multiple sources, data science as a field is quickly emerging. Data science refers to interdisciplinary field about scientific methods, processes, and systems to extract knowledge or insights from data in various forms, structured or unstructured, similar to data mining. The key highlight of the definition is “insights” as it means generating findings which are previously not known from traditional data mining techniques or simple trend and regression analysis. That is why data science as a field is considered to be at an intersection of mathematics, statistics, software and business domain knowledge. One of the simplest examples of usage of data science for any company is its ability to predict customer churn in advance. It can help the company to work on the customer retention instead of focusing only on costlier customer acquisition.

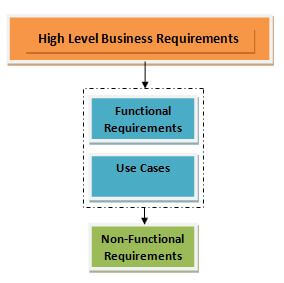

While there are various tools available in the market for data science, but a very critical part for success of any data science initiative is defining the use cases from business standpoint. In most companies, technology teams are adept at understanding the data and running analysis over them. However, field of data science in unique in a way as the teams can sometimes not know what they are looking for in the data as the insights may mostly not be a established fact. Hence the role of business analyst becomes so critical in this field as you would need a person who is fluent not only in the IT domain but also speak in the language of business leaders.

For example, data science business analyst would be expected to convert the business problem statement “Given past performance and current trends, what is the likely outcome of a certain action” to an IT problem statement which means what data needs to be analyzed to arrive at the insights. The data would then be reviewed with the technology team and results would be delivered to the business team in form of insights and data patterns. Business analyst should also be knowledgeable enough to apply various predictive modeling techniques and right model selection for generating insights for the problem at hand.

One would argue, what’s the difference between a business analyst in data science domain compared to a general business analyst. One of the key skills, which differentiate the data science business analyst, is its deep understanding of data as well as industry and functional expertise, which would enable him/her to understand the business context and identify the use case. Data science business analyst is required to have deep business knowledge and understanding of data as depth and breadth of data increases. Further, business analyst would also have to work alongside with business and technical teams and should be comfortable speaking in their language. Mckinsey in its report on “The age of analytics” mentions that while data scientist is a critical skill, companies need “translator” who serves as the link between analytical talent and practical applications to business questions. Mckinsey also highlights that first of the five critical elements for establishing successful data and analytics transformation require use cases which are also defined as source of value. The uses cases should clearly articulate the business need and projected impact.

Another key role of the business analyst for data science assignments is to identify the “optimal” model for the data based use case at hand. The business analyst should possess the knowledge to frame the right hypothesis to test it. Albert Einstein once said, “If I were given one hour to save the world, I would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and one minute solving it.” In simple terms, business analyst puts a framework to the problem solving process. Business Analyst should be able to answer questions like:

- “What is clustering or regression and when should I use these techniques?”

- “How do I formulate a hypothesis on my data?”

Most companies are not able to realize the true potential from data science assignments as they rely heavily on data scientists who are very proficient at data preparation, cleaning and modeling or writing software code via tools like python, R but lack the domain knowledge and meaning of data in business context. This is where the business analyst plays a very crucial role of bridging the divide between the business teams and IT department for complex data science assignments.