Beyond Requirements Analysis – Enterprise Analysis

“What do your Business Analysts do?”

“They develop and manage project requirements, of course. What else would they do?”

What else indeed!

The BA Body of Knowledge (BABOK®) defines what a professional BA should know and do. Much of it is focused on requirements work – but not all. One of the knowledge areas that takes the BA beyond requirements work is “Enterprise Analysis.”

Enterprise Analysis (EA) encompasses those activities that the job title “Business Analyst” actually points toward: analyzing business processes. The majority of these activities is outside of projects, and in fact, put the BA into the position of recommending and justifying projects.

Enterprise Analysis

Analyzing business processes is indeed a big part of what we do during Requirements Analysis. But that is not the only context where this analysis should be done, and in fact, it is not the most valuable time to do it. In the Enterprise Analysis knowledge area, the BABOK identifies several other contexts in which such analysis should be done.

Activity: Creating and Maintaining the Business Architecture

As the name of this activity implies, “Creating and Maintaining the Business Architecture” is an on-going activity that has as its focus the entire enterprise. The “Business Architecture” is a model of all the business processes that are used throughout the enterprise. It shows how they work and relate to each other.

The net result of this is an understanding that most organizations lack, of how all their moving parts mesh with each other. This broad understanding of the enterprise’s processes becomes the foundation for all of the other responsibilities of the BA. But its bigger value comes in providing every member of the organization with a clear understanding of how his or her department and individual job fits into the bigger picture

Recommending and Justifying Projects

The bulk of the activities described in the Enterprise Analysis knowledge area center around proposing and justifying projects. These are activities that occur in some form or other in any organization. But with the BA’s involvement, they can provide much more value and ensure the organization’s resources are spent on the most valuable projects.

Activity: Conducting Feasibility Studies

Projects are created to solve a problem or to take advantage of an opportunity. It is rare for there to be only one available solution to a problem or opportunity, so part of project initiation involves exploring the alternatives. The BA can provide a valuable service by calling upon his or her understanding of the Business Architecture to analyze the feasibility of a variety of options.

Activity: Determining Project Scope

Scope definition should not be the first step in requirements development; it should be done during the project proposal process. How can the decision-maker(s) approve or disapprove a project without a clear understanding of its boundaries?

Activity: Preparing the Business Case

The business case is the logical argument for embarking on a project. It consists of contrasting the status quo (current situation) with the various options for addressing the problem or opportunity at hand and recommending the most appropriate option. In most cases, these options are being contrasted in terms of money (e.g., “If we spend $x on this project, it will result in $y increased revenue per year”).

Activity: Conducting the Initial Risk Assessment

An important piece of information that the decision-makers need is an understanding of the risks involved in a project. Clearly, you cannot do a complete risk-planning workshop before the project has been initiated (that is part of the Project Planning process). But an initial survey of the project risks can provide the decision-makers with key information.

Activity: Preparing the Decision Package

The BA has no authority to approve or disapprove any project. The people who do have that authority rarely have the time that is necessary to do the requisite research. So, the BA’s role in the decision-making process is to do all of the necessary research, and compile it into a form the decision-makers can use.

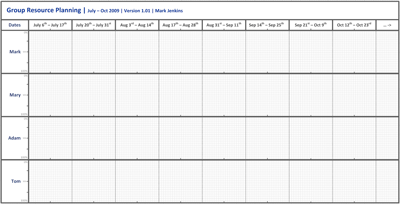

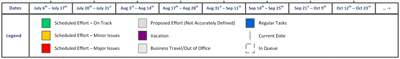

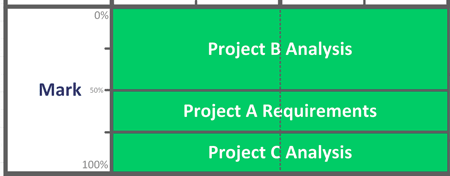

Activity: Selecting and Prioritizing Projects

After a project has been approved, it should not be a foregone conclusion that it will begin immediately. Projects must be prioritized against each other so the organization’s resources can be deployed in the most appropriate way. Again, the BA is not the decision-maker, but provides the necessary analysis to the decision-makers.

Project Work beyond Requirements

The last three activities that the BABOK includes under the “Enterprise Analysis” knowledge area are project-related activities that go beyond Requirements Analysis. They continue the theme of Enterprise Analysis by maintaining a broad organizational view of the project.

Activity: Launching New Projects

Here, the BA works with the appropriate people in the organization to ensure that the necessary resources, including the right project manager, are committed to the project. The BA’s unique role in these activities is to focus on the bigger picture of why the project was approved and how it fits into the bigger organizational context. This ensures that the intent of the decision-makers is honored as the project is framed and kicked off.

Activity: Managing Projects for Value

In this activity, the BA works closely with the project manager to ensure the project is tracking toward providing the value that was promised in the business case (above). The BA helps the project manager keep the project’s value proposition on track. And if the assumptions on which the project was approved turn out to be false, the BA can help the decision-makers determine their best response.

Activity: Tracking Project Benefits

In this last activity, the BA closes the loop on the business case (above). The business case proposed making certain investments in order to accrue certain benefits. After the project is over, the actual investments are known, and the actual benefits can be measured. At some appropriate time after deployment, the BA should report back to the decision-makers about how the results of the project compare with the business case. This discussion process will help the organization make better decisions in the future.

Expanding Your Value as a BA

Requirements Analysis is an important way for the BA to provide value to his or her organization. By adding Enterprise Analysis, the BA can dramatically increase his or her value by ensuring that every project fits well into the bigger picture and provides the best possible result to the organization.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below

Alan S. Koch, PMP is a speaker and writer on effective Project Management Methods. He is a certified Project Management Professional and President of ASK Process, Inc, a training and consulting company that helps companies to improve the return on their software investment by focusing on the quality of both their software products and the processes they use to develop them.

Mr. Koch’s 29 years in software development include:14 years designing, developing and maintaining software; five plus years in Quality Assurance (including establishing and managing a QA department); eight years in Software Process Improvement and 10 years in management

Mr. Koch was with the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) for 13 years where he became familiar with the Capability Maturity Model (CMM), earned the authorization to teach the Personal Software Process (PSP) and worked with Watts Humphrey in pilot testing the Team Software Process (TSP).

For more information about Mr. Koch: http://www.ASKProcess.com/experience.html.

This article was originally published in Global Knowledge’s Business Brief newsletter. (www.globalknowledge.com)

Copyright © Global Knowledge Training LLC. All rights reserved