Deep Dive Models in Agile Series: Decision Models, Edition 6

This short paper series, “Deep Dive Models in Agile,” provides valuable information for the Product Owner community to use additional good practices in their projects.

In each paper in this series, we take one of the most commonly used visual models in agile and explain how to create one and how to use one to help build, groom, or elaborate your agile backlog.

This is the last paper in this current series and covers Decision Models, which include both Decision Trees and Decision Tables. Previous articles in this series included Process Flows, Feature Trees, Business Objectives Models, Business Data Diagrams and State Models.

What is a Decision Model?

Decision Models include two RML System models (Decision Trees and Decision Tables) that detail the system logic that either controls user functions or decides what actions a system will take in various circumstances.

Like the State Models, these two models are covered together in this paper because they show the same information in different formats. Oftentimes a PO or BA will use only one or the other of the two Decision Models based on circumstances. Decision Tables are used when the PO or BA wants to ensure that every permutation of applicable decision choices has been explored. Whereas, Decision Trees are more consumable for business stakeholders and are typically used to show a collapsed view of a Decision Tree by only modeling the decision choices that lead to an outcome. Decision Models are great for any project with logic that the system needs to enforce and even as the acceptance criteria for the user stories in some cases!

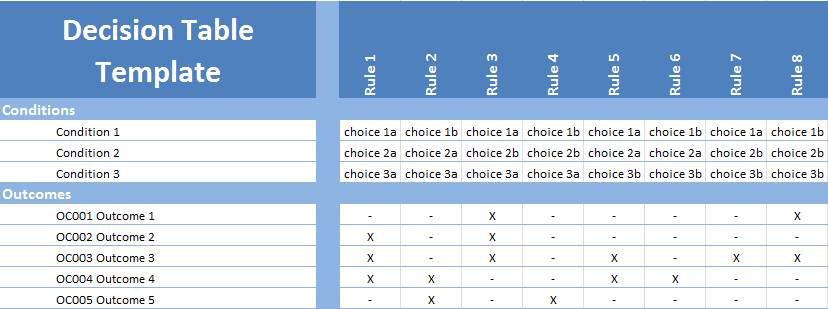

The Decision Table is the tabular format of decisions and their outcomes with each column in the Decision Table representing one potential permutation of decisions in the system. The Decision Table contains three main areas: the conditions (or decisions), the outcomes, and the columns where each permutation of each decision choice is listed with the appropriate outcomes marked. This model is read vertically (see example below) in that the user will take one column and read down: “If Condition 1 is choice 1a, condition 2 is choice 2a and condition 3 is choice 3a, then outcomes 2, 3 and 4 occur. The vertical columns each represent a business rule for the system.

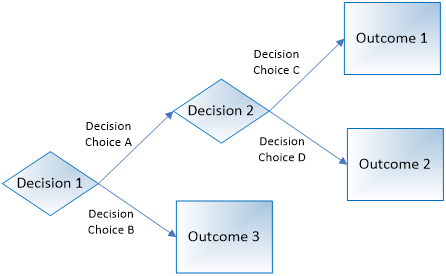

A Decision Tree, like the State Diagram, is a more visual way to show the decision logic in a branching tree format by only showing the decisions and choices combinations that lead to an outcome in the system. This model is great for verifying branches of system logic with business stakeholders. See the example of a decision tree below:

When would I use a Decision Model on an agile project?

There are two main use cases for Decision Models on agile projects. One is to detail specific pieces of system logic for a user story. In this case, the Decision Model is identified and created for the user story it supports about 1-2 sprints ahead of the sprint the decision logic will be implemented in. The PO or BA would identify that a user story requires the system to execute decision logic to come up with a response for the user. This can be identified by the PO or BA during elicitation if she hears words like “If the user does X, then the system does Y, etc.” From there, the PO or BA would elicit all the possible decisions that occur in the system and walk systematically through each combination of decision choices in a Decision Table to ensure that all outcomes are accounted for. Optionally, a Decision Tree can be created to ask questions of business stakeholders and complete the system logic.

The alternative use for using Decision Models on an agile project is to identify and represent the acceptance criteria. Acceptance criteria are often written in the Given-When-Then format. “Given a certain precondition in the system, when some trigger occurs, then the system will take some action or display some response.” This aligns very well to a Decision Table as the preconditions and triggers can be modeled as decisions or conditions, and the outcomes are still outcomes in the Decision Table. One caution here is that if written acceptance criteria already exist in the Given-When-Then format, the PO or BA usually does not need to create a Decision Table to model the acceptance criteria. This technique would only be used on larger stories where the precondition list or trigger list is longer (3-5), and thus the number of combinations of preconditions and triggers is higher. In this way, the PO or BA can be sure that every path in the acceptance criteria has been explored to find any needed system response.

How do I create a Decision Model?

The first step in creating a Decision Model is for the PO or BA to identify all the decisions being made by the system for a particular outcome. This can be a list in the Decision Table or decision diamonds in the Decision Tree. Typically, a PO or BA will start with a Decision Table and move to a Decision Tree as needed.

After brainstorming the decisions in the system, the PO or BA has to identify all the applicable choices for each decision. Decisions can be binary (Y/N) or non-binary. If the decision is non-binary, the PO or BA needs to check that the decision choices are Mutually Exclusive and Collectively Exhaustive (MECE). This means that all choices are accounted for and that there is no ambiguity in choices (if a number is a non-integer, choices like 1, 2-5 and >5 would not meet MECE and instead, the PO or BA would need something like: <1, >=1 to <5, >=5). For this reason, a lot of POs/BAs prefer to use binary decisions, but it can complicate a table or tree.

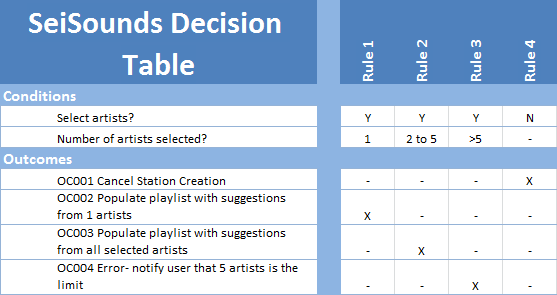

Finally, the PO or BA walks through each combination of decision choices and identifies the appropriate system outcome for that combination of decisions. See the example Decision Table below:

In this case, if the listener chooses not to select artists, then the system cancels station creation and doesn’t care about the number of artists chosen. In Decision Tables, this case, where the choice of the decision or condition doesn’t matter, can be shown as a “-.“ Additionally, Decision Tables can show ordered outcomes by using numbers in the outcomes (i.e. 1 and 2). For example, in an e-commerce site, when a customer wants to use a gift card to pay for something, the system may first (1) deplete all funds on the gift card and then (2) ask for a second payment method if the gift card did not cover the full cost of the order.

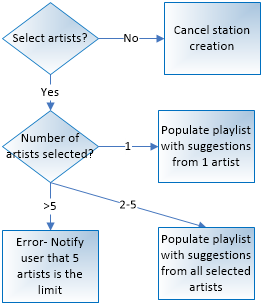

Decision Trees show this same information in a branching tree format using the same elements as the Process Flow: steps and decision diamonds, except the steps are now steps the system takes in the form of outcomes. As mentioned above, Decision Trees are usually created after Decision Table to verify the decision logic with business stakeholders. However, if the PO or BA decides to start with the Decision Tree, the process for creation is essentially the same: 1- brainstorm the decisions, 2- identify the choices and 3- walk through the decision/choice combinations to arrive at outcomes. See the example below:

How do I derive user stories out of a Decision Model?

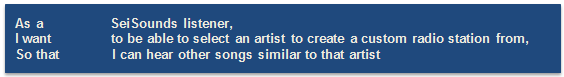

Decision Models usually supplement user stories to ensure that all paths are identified, so they usually lead to additional acceptance criteria. Each Decision Model created will usually be for a single user story, and each permutation of decisions and choices is one acceptance criteria. For example, if we had a story of:

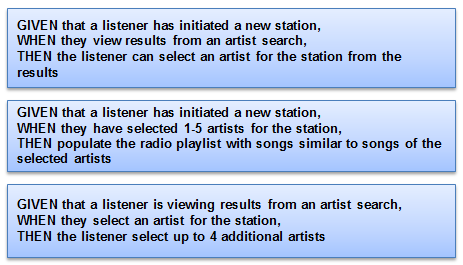

With acceptance criteria of:

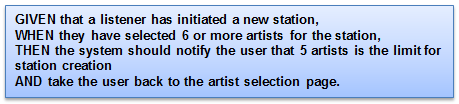

The PO or BA might see the need to create the Decision Models above to ensure that all acceptance criteria are accounted for, which would identify the following acceptance criteria:

These models are great for identifying missing acceptance criteria (and thus test cases) that might trip up an agile team and cause a story to “Fail” a sprint by not considering exception cases in the acceptance criteria.

Conclusion

Decision Models are great models for POs or BAs to use when they are unsure they have properly captured the acceptance criteria for a story. These models allow the PO or BA and business stakeholders to be aligned on the system logic and expected system behavior before a story is taken into a sprint which allows the PO or BA to give better information to the agile team.

This concludes the Deep Dive Models in Agile series. Over the course of six short papers, we have covered: Process Flows, Feature Trees, Business Objectives Models, Business Data Diagram, State Models and Decision Models. Which visual models do you use most on your agile projects?