Terms, Terms, Terms. Clarifying Some Business Analysis and Project Management Terms

In order to clarify some basic concepts of business analysis and project management, we need to distinguish between terms that seem similar but are not. Below are some foundational terms and distinctions.

1. Project Management focuses on the work and methods to create new products. The Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide – Fourth Edition) defines project management as “the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet the project requirements.”[1]

2. Process Management concentrates on the workflow and systems that recreate the products that sustain an organization.

3. Products. Throughout this article, we’ll refer to the end result of the project as the product. It can be a product, service, or any key deliverable that is produced as a result of the project. A few examples of products include a new bridge, a new methodology, landscaping, a project management office, a new car, a feasibility study, an HOV lane added to a freeway, a recommendation, a new or changed process, a new banking service, a new website, creation of a new agency, and a new marketing campaign.

4. Product Management uses processes and knowledge to manage product development, support, and marketing of the product. In this article, we cover the part of product management that occurs prior to deploying, selling, and supporting the end product. We focus on the work needed to define the requirements of the end product, to ensure that those requirements are built into the product and tested, and to ensure that the end product meets those requirements. Product managers exist in some organizations as the driving force behind new product development. They often define the high-level product requirements. In such organizations, this product manager often fills the role of project sponsor. See Table 1.1 for a summary.

| Characteristic | Projects | Product Requirements |

Processes |

| Ownership | Sponsor | Sponsor | Sponsor |

| Keeper or custodian |

Project manager | Business analyst | Business process analyst |

| Planning | Project management plan | Requirements management plan | Documented processes |

| Execution | Performing project execution |

Performing BA activities | Performing the process steps |

| Closeout | Project close and lessons learned | Closeout of phase(s) & lessons learned | Improved processes |

| Aligns with organizational vision and strategy? | Must | Must | Must |

Project, Process, and Product Requirement Characteristics

Projects are initiated in a variety of different ways, such as new government regulations, competitive market forces, and requests to enhance existing products. In other words, someone in the organization requests a new or changed product.

The person who initiates the request is called the sponsor. We’ll explain the full sponsor role later, but for now let’s think of the sponsor as the person who obtains the funds for the project and makes key business decisions.

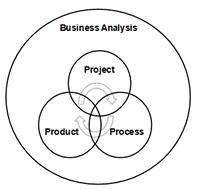

Once the request has been approved, a project manager can be assigned to manage the project. Projects result in changed processes for an individual or group of individuals large or small. For example, a new bridge results in new traffic patterns and new processes for those taking the bridge. Landscaping requires processes to maintain it; the HOV lane requires new laws and new processes for use by drivers. A new computer system results in new processes for the end-user. Therefore, stakeholders affected by projects, processes, and products all need to be identified and kept informed of the project status. Figure 1 below shows the interrelationship of projects, processes, and products.

Figure 1: Projects, Processes and Product Requirements Interaction

Life Cycles, Phases, and Methodologies

Project Life Cycle. A project life cycle takes the project from its inception to its conclusion. In other words, each project is alive. It is conceived, born, it matures, and finally ends. Products have their own life cycles. Typically, product life cycles last longer than project life cycles, because in general the product outlasts the project. However, in the example of a lengthy feasibility study whose product is a recommendation, the life cycle of the project can last longer than the end product. Project life cycles are composed of one or more project phases.

Project Phase. The project phase,as described above, usually marks a milestone, at which point a deliverable is usually produced, reviewed, and approved. The business analysis phase(s), then, produces a set of requirements (features and functions) that must be reviewed and approved.

The names of the project phases do not have to be the same for each project. One organization may have projects in different divisions or business units or agencies, all of whom can have different phase names. Nor are there a set number of phases required for each project. For example, the number of business analysis phases for a software development project can vary, depending on the approach taken to business analysis and the phase-to-phase relationship used. The business analysis effort can occur during one project phase or over the course of many project phases. For example, iterative development of software projects occurs over several project phases, as could the piloting of new business processes. For a complete discussion of lifecycles and phases, please refer to the PMBOK® Guide – Fourth Edition, section 2.1.2.

Methodology. This prescribes how to get through the project life cycle, including the business analysis phase(s). It usually includes processes, procedures, forms, and templates for completing the project or project phase. Each project phase could, but does not have to, follow the same methodology. There are methodologies for completing business analysis, project management, product development, and testing to name a few.

Iterations, Increments, and Releases

These terms have created a great deal of confusion over the last several years. In the blog Don’t Know What I Want But I Know How to Get It, Jeff Patton uses art, movies, and pop music to explain the difference between “iterating and incrementing.”[2]

In a PowerPoint presentation, Managing Increments and Iterations with “V-W” Staging, Alistair Cockburn distinguishes iterations and increments by referring to increments as “build, deliver, learn, build, deliver, learn,” and iterations as “build, examine, learn, rebuild, ship.”[3] For another short differentiation, see Kevlin Henney’s article from December, 2007.[4]

Incremental development implies that new features and functions are added with each increment. For example, software can be developed using a plan-driven approach, with increments or new functionality added incrementally. Incremental business analysis implies that requirements are defined for an increment, and new requirements are added for each increment. Again, releasing in increments is appropriate for both plan-driven and change-driven approaches.

Iterative development implies planned rework. We expect the product requirements to evolve and change, so that change is viewed as part of the development process, not as a defect. Each iteration evaluates what has been built, and the product is rebuilt as needed. Iteration implies planned rework, because not only do we expect requirements to evolve, but there is a process to handle changes iteratively. Change-driven business analysis combines incremental and iterative requirements definition.

Product and Solution

Although the industry sometimes treats these two terms synonymously, we will use the term “product” for the end result of the project, and the term “solution” to mean the implementation of the requirements. The solution is a term used to describe a set of key deliverables that when taken together solve the business problem for which the project is undertaken.

Here are some examples.

- The productof a project is a new marketing campaign. One solutionmight be to hire a consulting firm to produce the campaign. Another solutionmight be to have the advertising department develop it.

- The productof a project is a new piece of software. One solutionmight be to build the software. Another solutionmight be to buy it from a vendor. Yet another solutionincludes new software, new hardware, and new processes.

- The product of a project is a new order replenishment system. One solution might be the software, hardware, new and changed processes, and a recommendation on whether or not the organization is ready for the change. The requirements describe the features, functions, and capability of the new system. The deliverables (work products) from business analysis include a business requirements document, a recommendation on new hardware, a model of the future processes, and a recommendation on a new organizational structure for the affected business units. The order replenishment system alone will not solve the business problem, so the solution has to include more than just the system. This solution may involve many projects, each of which will have products.

Summary

Making distinctions in terminology is important for both planning and execution of projects, and common language can help reduce misunderstanding and miscommunication. When everyone understands the underlying concepts of business analysis and project management and uses the same terminology, they can complete the work more productively and with less conflict.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below

Elizabeth Larson, CBAP, PMP, CSM, and Richard Larson, CBAP, PMP, are Co-Principals of Watermark Learning (http://www.watermarklearning.com/), a globally recognized business analysis and project management training company. For over 20 years, they have used their extensive experience in both business analysis and project management to help thousands of BA and PM practitioners develop new skills. They have helped build Watermark’s training into a unique combination of industry best practices, an engaging format, and a practical approach. Watermark Learning students immediately learn the real-world skills necessary to produce enduring results. Both Elizabeth and Richard are among the world’s first Certified Business Analysis Professionals (C BAP ) through the International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA) and are contributors to the IIBA Business Analysis Body of Knowledge (BABOK). They are also certified Project Management Professionals (PMP) and are contributors to the section on collecting requirements in the 4th edition of the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK).

Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Fourth Edition (PMB[1] Project OK® Guide). Newton Square, Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, 2008. p. 435.

Patton, Jeff. “Don’t know what I want, but I know how to get it.” Agile Product Design. 21 Jan. 2008. <http://www.agileproductdesign.com/blog/dont_know_what_i_want.html>.

Cockburn, Alistair, “Managing Increments and Iterations with ‘V-W’ Staging.” <http://alistair.cockburn.us/>.

Henney, Kevin. “Iterative and Incremental Development Explained.” Search Software Quality. 3 Dec. 2007. 29 Jan. 2009 <http://searchsoftwarequality.techtarget./news/article/0,289142,sid92_%20gci1284193,00.html>.

I recently ran across this quote from

I recently ran across this quote from

Making a successful business case for your new project is the winning way to ensure a good beginning for your team. How often have you been asked to “work the numbers” and provide a basis for a compelling project? Often, if you are a project manager with responsibility to help your sponsor and your company make decisions about which projects are the right ones to do. The PMBOK provides the body of knowledge for “doing it the right way.” In this article, you will learn about the five steps of a methodology that you can take away and use everyday for identifying, selecting, and justifying a new project or a significant change in scope to an ongoing project.

Making a successful business case for your new project is the winning way to ensure a good beginning for your team. How often have you been asked to “work the numbers” and provide a basis for a compelling project? Often, if you are a project manager with responsibility to help your sponsor and your company make decisions about which projects are the right ones to do. The PMBOK provides the body of knowledge for “doing it the right way.” In this article, you will learn about the five steps of a methodology that you can take away and use everyday for identifying, selecting, and justifying a new project or a significant change in scope to an ongoing project.