The Business Climate

In the twenty-first century, business processes have become more complex; i.e., more interconnected, interdependent, and interrelated than ever before. Businesses today are rejecting traditional organizational structures to create complex communities comprised of alliances with strategic suppliers, outsourcing vendors, networks of customers, and partnerships with key political groups, regulatory entities, and even competitors. Through these alliances, organizations are addressing the pressures of unprecedented change, global competition, time-to-market compression, rapidly changing technologies, and increasing complexity at every turn. Since business systems are significantly more complex than ever, projects that implement new business systems are also more complex. To reap the rewards of significant, large-scale business transformation initiatives, designed to not only keep organizations in the game but make them a major player, we must be able to manage complex business transformation projects.

Why Now?

Centers of excellence are emerging as a vital strategic asset to serve as the primary vehicle for managing complex change initiatives. A center of excellence is a team of people that is established to promote collaboration and the application of best practices (Geiger, Jonathan G. Intelligent Solutions: Establishing a Center of Excellence. BIReview: March 20, 2007. http://www.bireview.com/article.cfm?articleid=222). Centers of excellence exist to bring about an enterprise focus to many business issues, e.g., data integration, project management, enterprise architecture, business and IT optimization, and enterprise-wide access to information. The concept of centers of excellence (COE) is quickly maturing in twenty-first century organizations because of the need to collaboratively determine solutions to complex business issues. Project management offices (PMO), a type of COE, proliferated in the 1990s as a centralized approach to managing projects, in response to the challenges associated with complex projects in an environment with low levels of project management maturity and governance. Industry leaders are effectively using various types of COEs, and BACOEs are among them.

A Slippery Slope

We are fortunate to have learned from the implementations of PMOs. The Project Management Institute’s research program studied PMOs in an attempt to publish a PMO standard. However, they were unable to do so, because they found out that there is no real standard practice for PMOs (Hobbs, 2007 PMI PMO Research Report). Here is what they discovered:

- PMOs have been prevalent since the mid 1990s; yet, most have been in existence for two years or less

- Only 50% of PMOs are seen as relevant and adding value

- Most operate autonomously from other PMOs

- Most organizations have trouble finding the right “fit” culturally and politically

- Closure and restructuring happens frequently

- Implementation time takes six months to two years; yet, there is a short time to demonstrate value before being closed or restructured; many are closed or restructured before they are completely implemented

- There is a wide variability in the percentage of projects within the mandate of the PMO

- Either all or none of the project managers are located within the PMO

- Most PMOs have a very small staff due to the key issue of cost

Conclusions: it is a difficult endeavor to establish a center of excellence that is accepted and supported by the organization. A considerable amount of due diligence is needed to make sure the new center is successful.

It’s About Value

For a BACOE to be viewed as adding value, one of the critical functions is benefits management, a continuous process of identifying new opportunities, envisioning results, implementing, checking intermediate results, and dynamically adjusting the path leading from investments to business results. Therefore, the role of the high-value BACOE is multidimensional, including: (1) provide thought leadership for all initiatives to confirm that the organization’s business analysis standards are maintained and adhered to, (2) conduct feasibility studies and prepare business cases for proposed new projects, (3) participate in all strategic initiatives by providing expert business analysis resources, and (4) conduct benefits management to ensure strategic change initiatives provide the value that was expected. The BACOE is staffed with business/technology experts, who can act as a central point of contact to facilitate collaboration among the lines of business and the IT groups.

Implementation Considerations

Integration

Although the BACOE is by definition business focused, it is of paramount importance for successful centers to operate in an environment where business operations and IT are aligned and in synch. In addition, the disciplines of project management, software design and development, and business analysis must be integrated. Therefore, to achieve a balanced perspective, it is important to involve business operations, IT, PMO representatives and project managers, and representatives from the project governance group in the design of the BACOE. Indeed, your organization may already have one or more centers of excellence. If that is the case, consideration should be made to combining them into one centralized center focused on program and project excellence. The goal is for a cross-functional team of experts (business visionary, technology expert, project manager and business analyst) to address the full solution life cycle from business case development to continuous improvement and support of the solution for all major projects.

Mission

Understanding the business drivers behind establishing the BACOE is of paramount importance. The motive behind establishing the center must be unambiguous, since it will serve as the foundation to establish the purpose, objectives, scope, and functions of the center. The desire to set up a BACOE might have originated in IT, because of the number of strategic, mission-critical IT projects impacting the whole organization, or in a particular business area that is experiencing a significant level of change. Whatever the genesis, strive to place the center so that it serves the entire enterprise, not just IT or a particular business area.

Placement

One of the biggest challenges for the BACOE is to bridge the gap that divides business and IT. To do so, the BACOE must deliver multidimensional services to the many diverse groups. Regardless of whether there is one COE, or several more narrowly focused models, the BACOE organization should be centralized. “Organizations with centralized COEs have better consistency and coordination, leading directly to less duplication of effort. These organizations configure and develop their IT systems by business processes rather than by business unit, leading to more efficient and more streamlined systems operations” (2006 USAG/SAP Best Practices Survey: Centers of Excellence: Optimize Your Business and IT Value. SAP America Inc. February 16, 2007). Best-in-class BACOEs evaluate the impact of proposed changes on all areas of the business and effectively allocate resources and support services according to business priorities.

Positioning is equated with authority in organizational structures; the higher the placement, the more autonomy, authority and responsibility is likely to be bestowed on the center. Therefore, positioning the center at the highest level possible provides the “measure of autonomy necessary to extend the authority across the organization, while substantiating the value and importance the function has in the eyes of executive management” (Bolles, Dennis PMP. Building Project Management Centers of Excellence. New York, NY: American Management Association. 2002). In the absence of high-level positioning, the success and impact of the center will likely be significantly diminished.

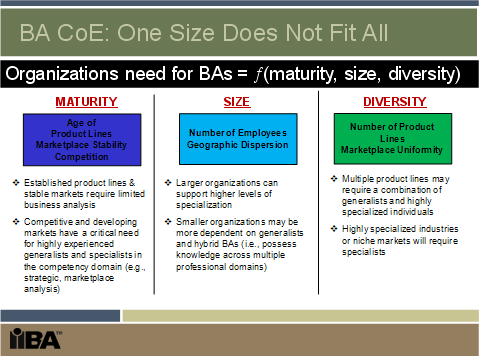

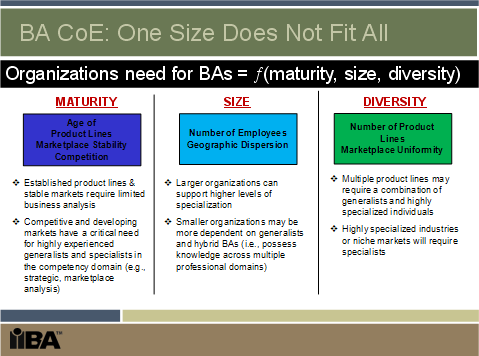

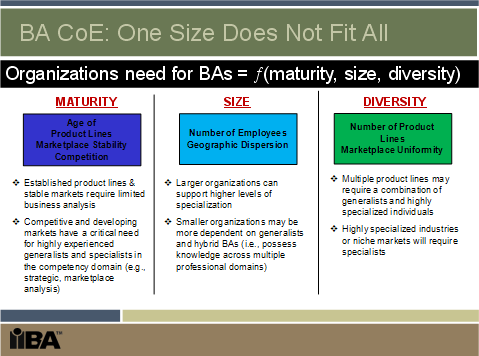

One Size does not fit All

The “perfect fit” takes several elements into consideration:

- The maturity of the organization’s processes and capabilities

- The size of the organization

- The diversity of the products and services

What is the Focus?

The current state of the organization must be taken into consideration, as in the effectiveness of the strategic planning and project portfolio management practices, the business performance management processes and strategies, the maturity of IT architecture, development and support processes, and the strength of the business focus across the enterprise. Clearly, organizations with more mature practices achieve higher levels of value from their COEs. Organizations can absorb a limited amount of concurrent change, while maintaining productivity levels, at any given time. Therefore, a gradual approach to implementing the BACOE is recommended. One option is to adopt a three-phased approach moving across the BACOE maturity continuum from a project-focused structure to a strategic organizational model.

Where to Start?

Based on the history of best practices for setting up centers of excellence, there is a proven implementation approach, including the steps listed below.

- Visioning and concept definition

- Assessing the organizational knowledge, skills, maturity, and mastery of business analysis practices

- Establishing BACOE implementation plans

- Finalizing plans and creating action teams to develop and implement the infrastructure for the center

Visioning

It is important to create a vision for the new center. Create a preliminary vision and mission statement for the center, and develop the concept in enough detail to prepare a business case for establishing the center. Vet the proposal with key stakeholders and secure approval to conduct the assessment of business analysis practices and plan for the implementation of the center.

During meetings with the key stakeholders, secure buy-in and support for the concept. Large-scale organizational change of this nature typically involves restructurings, cultural transformation, new technologies, and forging new partnerships. Handling change can well mean the difference between success and failure of the effort. Techniques to consider during the visioning phase include (Kotter, John P. (2002) Getting to the Heart of How to Make Change Happen. Boston, MA: Harvard Business):

- Executive sponsorship – A center of excellence cannot exist successfully without an executive sponsor. Build a trusting, collaborative relationship with the sponsor, seeking mentoring and coaching at every turn.

- Political management strategy – Conduct an analysis of key stakeholders to determine those who can influence the center, and whether they feel positively or negatively about the center. Identify the goals of the key stakeholders. Assess the political environment. Define problems, solutions, and action plans to take advantage of positive influences, and to neutralize negative ones.

- A sense of urgency – Work with stakeholder groups to reduce complacency, fear, and anger over the change, and to increase their sense of urgency.

- The guiding team – Build a team of supporters who have the credibility, skills, connections, reputations, and formal authority to provide the necessary leadership to help shape the BACOE.

- The vision – Use the guiding team to develop a clear, simple, compelling vision for the BACOE, and set of strategies to achieve the vision.

- Communication for buy-in – Execute a simple, straight-forward communication plan using forceful and convincing messages sent through many channels. Use the guiding team to promote the vision whenever possible.

- Empowerment for action – Use the guiding team to remove barriers to change, including disempowering management styles, antiquated business processes, and inadequate information.

- Short-term wins – Wins create enthusiasm and momentum. Plan the implementation to achieve early successes.

- Dependency management – The success of the center is likely dependent on coordination with other groups in the organization. Assign someone from your core team as the dependency owner, to liaise with each dependent group. A best practice is for dependency owners to attend team meetings of the dependent group, so as to demonstrate the importance of the relationship and to solicit feedback and recommendations for improvements.

Organizational Readiness

The purpose of the organizational readiness assessment is to determine organizational expectations for the BACOE and to gauge the cultural readiness for the change. Form a small assessment team to determine key challenges, gaps and issues that should be addressed immediately. The ideal assessment solution is to conduct a formal organizational maturity assessment. However, a less formal assessment may suffice at this point.

Planning

Develop a BACOE Business Plan and Charter that describes the center in detail. Planning considerations include the elements listed in the table below. It is helpful to draft the plan and charter, and then conduct a BACOE kickoff workshop where they are viewed, refined and approved.

|

Planning Considerations

|

Description of Kick-off Workshop Agenda Items

|

| Strategic Alignment, Vision and Mission |

Present the case for the BACOE, and reference the business case for more detailed information about cost versus benefits of the center. |

| Assessment Results |

Include or reference the results of the assessments that were conducted:

- Maturity of the business analysis practices

- Summary of the skill assessments

- Recommendations, including training and professional development of BAs and improvement of business analysis practice standards

|

| Scope |

Describe the scope of responsibilities of the BACOE, including:

- The professional disciplines guided by the center, (i.e., PM and BA, just BA)

- The functions the center will perform

- The processes the center will standardize, monitor and continuously improve

- The metrics that will be tracked to determine the success of the center

|

| Authority |

Centers of excellence can be purely advisory, or they can have the authority to own and direct business processes. In practice, centers typically are advisory in some areas, and decision-makers in others. Remember, the organizational placement should be commensurate upon the authority and role of the center. When describing the authority of the COE, include the governance structure, i.e., who or what group the COE will report to for guidance and approval of activities. |

| Services |

A center of excellence is almost always a resource center, developing and maintaining information on best practices and lessons learned, and is often a resource assigning business analysts to projects. Document the proposed role:

- Materials to be provided, e.g., reference articles, templates, job aids, tools, procedures, methods, practices

- Services, e.g., business case development, portfolio management team support, consulting, mentoring, standards development, quality reviews, workshop facilitators, and providing business analysis resources to project teams

|

| Organization |

Describe the BACOE team structure, management, and operations including:

- Positions and their roles, responsibilities, and knowledge and skill requirements

- Reporting relationships

- Linkages to other organizational entities

|

| Budget and Staffing Levels |

At a high level, describe the proposed budget, including facilities, tools and technology, and staffing ramp up plans. |

| Implementation Approach |

Document formation of initial working groups to begin to build the foundational elements of the center. In addition, describe the organizational placement of the center, and the focus initially: (i.e., project centric, enterprise focus, or strategic focus). |

Launch

After the workshop session, finalize the BACOE Charter and Business Plan, and launch the center. Form working groups to develop business analysis practice standards, provide for education, training, mentoring and consulting support, and secure the needed facilities, tools, and supplies.

Final Words

Establishing centers of excellence is difficult, because it destabilizes the sense of balance and power within the organization. Ambiguities arise when all stakeholders are adjusting to the new model. These may manifest themselves as resistance to change, and can pose a risk to a successful implementation. Therefore, coordinate and communicate about how the center will affect roles and responsibilities accompanies the implementation of the center. Do not underestimate the challenges that you will encounter. Pay close attention to organizational change management strategies and use them liberally.

Value to the Organization

To establish BACOE to last, demonstrate the value the center brings to the organization. Develop measures of success and report progress to executives to demonstrate the value added to the organization because of the BACOE. Typical measures of success include:

- Project cost overrun reduction – Quantify the project time and cost overruns prior to the implementation of the BACOE, and for those projects that are supported by the BACOE. If a baseline measurement is not available in your organization, use industry standard benchmarks as a comparison. Other measures might be improvements to team member morale and reduction in project staff turnover. Be sure to include opportunity costs caused by the delayed implementation of the new solution.

- Project time and cost savings – Track the number of requirements defects discovered during testing and after the solution is in production prior to the implementation of the BACOE, and for those projects that are supported by the BACOE. Quantify the value in terms of reduced re-work costs and improved customer satisfaction.

- Project portfolio value – Prepare reports for the executive team that provide the investment costs and expected value of the portfolio of projects; report actual value new solutions add to the organization as compared to the expected value predicted in the business case.

Great Teams…You Need One!

When staffing the BACOE, establish a small but mighty core team dedicated full-time to the center, co-located, highly trained, and multi-skilled. Do not over staff the center, as the cost will seem prohibitive. Augment the core team’s efforts by bringing in subject matter experts and forming sub-teams as needed. Select team members not only because of their knowledge and skills, but also because they are passionate and love to work in a challenging, collaborative environment. Develop team-leadership skills and dedicate efforts to transitioning your group into a high-performing team with common values, beliefs, and a cultural foundation upon which to flourish.

Don’t forget to leave your comments below

Kathleen (Kitty) Hass is principle consultant, K. Hass and Associates, specializing in strategy execution, business analysis and project management disciplines. Ms. Hass is a prominent presenter at industry conferences, author and lecturer. Expertise includes implementing a mature BA Practice, implementing PMOs, BACOEs, and portfolio management, facilitating IT strategic planning, leading software-intensive projects, executive coaching, building and leading strategic project teams, and managing complex programs. Her company provides high-value facilitation and consulting services to agile and traditional organizations. Ms. Hass has provided professional services to Federal agencies, the intelligence community, and Fortune 500 companies. Professional certification include: SEI CMM appraiser, Baldrige National Quality Program examiner, Zenger-Miller facilitator, and Project Management Professional. She is Director at Large for IIBA and a member of the BABOK committee serving as lead author of the Enterprise Analysis chapter. She authored numerous white papers and articles on leading edge PM/BA practices, in 2008 published the Business Analysis Essential Library Series; Managing Project Complexity – A New Model, and in 2009 contributed to The 77 Deadly Sins of Project Management. Ms. Hass can be reache at [email protected]

This article was originally published June 2009 in ModernAnalyst.com www.modernanalyst.com

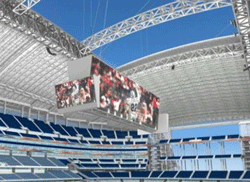

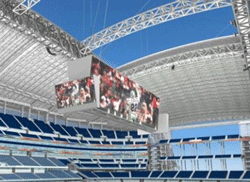

Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, who I do not love since I am a NY Giants fan, had a pet feature for this stadium…sixty yard long, high definition screens that are 90 feet above the field and run along the side lines.

Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, who I do not love since I am a NY Giants fan, had a pet feature for this stadium…sixty yard long, high definition screens that are 90 feet above the field and run along the side lines.